Small Man in a Book (37 page)

Read Small Man in a Book Online

Authors: Rob Brydon

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

Looking back at this period of my life now, I can see that all the strands and fragments of work that I had experienced, if not endured, over the years since leaving college were finally beginning to come together in a coherent way. While I had been trying, with a straight face, to sell Paula Yates Hand Cream (no, really) on the Shopping Channel ten years earlier, I had yearned for a move into the unattainable world of acting; in film, in a TV show, in a fringe theatre, anywhere but that brightly lit, smelling-of-make-up studio in Osterley. But I’m sure that the television shopping, the roving reporting, the radio-show hosting, even the playing of a thrush-cream salesman in a hotel in Glasgow, all contributed to the person who finally managed to produce some work he could be proud of.

It was during those few days spent driving around and filming the beginnings of

Marion and Geoff

that I finally gave an acting performance that represented what I’d hoped I was capable of, a performance that wasn’t forced or overplayed but that just

was

. I realized what I had been doing all these years whenever I’d had a chance to prove myself on something, such as

First Knight

, was simply overacting. I’d had a terror of trying to give a subtle, naturalistic performance and then looking up to see the director recoil in horror, saying, ‘Woah, woah, what are you doing?’ So, to deny anyone the chance, I would always crank it up just so they could see that I was doing something, I was ‘giving a performance’. It was always hard coming into a big production to play a small part, and having to judge the tone of the whole piece; my default mode was simply to go big, in the vain hope of being noticed. Sitting in the car was the first time I’d felt secure enough to try to give the sort of performance I admired in others. It was a wholly conscious decision, an effort to go for it and try to be the sort of actor I’d always wanted to be.

Alongside the excitement of finally being part of something good, something of quality, in July Martina gave birth to a beautiful baby girl, Amy. We now had gone girl/boy/girl, and I rather admired our completely random symmetry; it was as though we were planning a Eurovision act. I was present at the birth, as I had been for Katie and Harry – a nervous wreck, even more so than before, convinced that we had been lucky so far and surely something must go wrong this time?

Thankfully, it didn’t.

To describe this time of my life as an exciting period of creative rebirth might smack of hubris, but that’s really how it felt; as well as the good fortune of bumping into Hugo, I was once again in contact with another old friend, Julia Davis. After our More Fool Us days in her native Bath, Julia had seemed to vanish off the face of the earth, only to pop up again some years later after relocating to London. Rather than being intimidated by her surroundings and following my own deathly slow progress, from shopping channel to thrush convention, she had immediately begun to work with the very best people around. We would talk on the phone and I’d listen wide-eyed as she told me how she’d already been involved in projects with

Father Ted

creators Graham Linehan and Arthur Mathews, as well as the man on the cutting edge of the cutting edge, Chris Morris. One day, she called and said that she’d just got a job alongside the still-unknown Simon Pegg as one of two supporting actors on Steve Coogan’s forthcoming tour of the UK.

Wow. Gulp. Oh my. This was the one that I especially envied.

I had followed Steve’s career for a long time and had watched his television appearances with huge admiration, in particular the peerless

I’m Alan Partridge

. Martina and I used to watch the first series on the sofa, and at the end of each episode I’d look across at her with an expression that said, ‘Perfection.’ It was as though the programme had been made just for me. Knowing that Steve had started his professional life as a voice-over artist had seemed to me to be the much-needed proof that I might still, one day, be able to clamber across into the world of comedy.

On the day of her first rehearsal, I called Julia in the evening to ask how it had gone and to offer up that classic fan question: ‘What’s he like?’ I told her how I already had tickets to see the show when it came to the nearest venue to my home, the Reading Hexagon. Indeed, that was the next time I saw her – and the first time I met Steve. It was a brief meeting after the show, at a local hotel, where he was surrounded by well-wishers and some of the large travelling circus that made up the show’s cast and crew.

I drove home from the encounter elated and deflated all at once. I clearly wasn’t doing what I wanted to be doing with my career and, having spent just a little while with Steve and his acolytes, the world of which I had just enjoyed the most fleeting taste and wanted so much to inhabit seemed further away than ever. I had planned to mention to Steve that I’d made a videotape of a few characters I’d written, and maybe even suggest that I try to get it to him for his perusal. But when it came to the crunch I wimped out, once again afraid of rejection. Other than saying how much I’d enjoyed the show, I think all I did was mention that we had a mutual friend in Peter Serafinowicz – so, essentially, I came away from our meeting no closer to success than when I’d arrived. I returned to my life of voice-overs, ever so slightly depressed.

Eventually, the tour came into London and took up a residency at the Lyceum Theatre, where it was packed with fans for a record-breaking five-week run. Rather conveniently for me, the theatre was just up the road from where I was to be found every Friday afternoon, whipping out my funny voices, recording

The Treatment

for Radio Five. One such Friday, on my way through the West End to the recording at Bush House, I knocked on the stage door at the Lyceum and dropped off a copy of

An Extremely Unlucky Traffic Warden

for Julia, who had promised to pass it on. My hope was that it might at some point be opened and watched, while my expectation was that it would probably meet the fate of most of its siblings and return home, tail between its legs, landing with a defeated thud on the doormat.

The Treatment

was a weekly radio show looking back at the news of the last seven days. In front of a very small studio audience, and I mean

very

small – they made Derek Jameson’s lot look like the O2 – a panel of assorted wits and political writers would each read a prepared piece on a given subject before it was thrown open for discussion. The contributors were an eclectic mix. Comedy writers like David Quantick and Jane Bussmann, political journalists Peter Oborne, Patrick Hennessy and Kevin Maguire, and comedians Lucy Porter, Jo Caulfield and a pre-ascendant Graham Norton all appeared on the show. Their talks were punctuated by a series of sketches performed by the very talented Laura Shavin and myself, as a variety of characters real and imagined.

It was a very good show, although I soon tired of the lightweight nature of the sketches and began to resent being given a cassette with the voices of the politicians of the day lined up for me to learn to mimic. Doing voices was always just a laugh; as a rule of thumb, I only really do people I’m fond of, or admire, so being given a list tended to irk me. The production team was a great bunch of people, though, and I’d always look forward to spending time with them – especially the host, Stuart Maconie, a splendid northern chap, a gentleman broadcaster with a wonderfully dry and understated wit. Stuart is one of the few people to share with Rhys John and myself a love of the line, ‘What could possibly go wrong?’

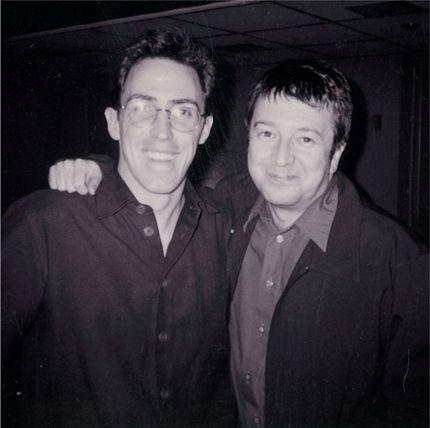

With Stuart Maconie at

The Treatment.

He and I soon had a list of sayings that would make each other laugh. When talking about my brief warm-ups in front of our threadbare studio audience, he would refer to me as, ‘Little Bobby Brydon … He fills the stage with flags.’ He would always have me in stitches as he’d drop into conversation, apropos of nothing, ‘What was it the doctor said, Rob? A complete mental and physical breakdown …’

I liked Stuart so much that, if you watch the first episode of

Marion and Geoff

, as Keith is driving through the night to Cardiff to gatecrash the anniversary party, Stuart’s is the voice of the contestant on the radio quiz. I’m the DJ. Such versatility.

There was a researcher on the show named Mark Mason, with whom I was friendly. Mark has gone on to become a published author with several titles to his name, but in those days his great love was blues guitar. He played at a club on Kingly Street, round the corner from the home of the floral-print shirt, Liberty. This was such a time of change for me (I was grabbing any and all chances to perform in front of an audience, whether it was brief spots at comedy clubs or warming up the regulars in

The Treatment

audience) so when Mark suggested I join him at one of his blues nights I jumped at the chance. I think we sang ‘Reconsider Baby’ (the Lowell Fulson song that I knew via Elvis’s version), along with James Taylor’s ‘Steamroller Blues’.

The bar was an intimate venue with a tiny stage at one end, and the performers would just step up and do their thing without much fuss. I went along three or four times and learned an important lesson from Mark, the very first time, when he noticed how I would sit back and wait for instruction from the band as to when to come in on a verse and when to sit out for a solo. He explained to me that I was in charge; I was the one who led the little band and decided who would do what. This seemingly obvious piece of advice was very significant for me – coming, as it did, at a time when I was beginning to take a bit more control of my working life and was becoming increasingly proactive. It was the realization that if you’re out front singing, in essence leading the band, then that’s what you have to do, you have to

lead

; you’re in charge, and you have to make the decisions. I was always too polite, waiting to be told when to come in. Since then, whenever I’m singing with a band I’ll always be sure to let them know where we’re going, with a hand gesture or a look. And whenever I do, I remember being in the little bar on Kingly Street with Mark.

One of the clearest memories from my time on

The Treatment

has nothing to do with comedy or music; it was the feeling I’d get after the recording, when everyone would reconvene at the bar of the BBC Club at Bush House for a few drinks. I was still teetotal and utterly bewildered at how content my colleagues would be to stay in the club for a couple of hours – talking, it seemed to me, about nothing in particular. I would have a Diet Coke and, after forty minutes or so, I’d make my excuses and leave – just as I’d done at teenage parties back in Porthcawl. This puritanical approach to pleasure became especially evident when the show escaped to Edinburgh for the Fringe Festival one August and we all found ourselves sharing a flat together. It was very much a ‘crash where you find a space’ arrangement – not one that I have ever endorsed (liking, as I do, excessive, perhaps even opulent comfort).

On the first night, the small flat soon filled up with friends and acquaintances, and before long everyone was under the influence of something or other. I’m sure it was just drink; I can’t imagine anyone in the media being interested in anything illegal. I of course was drinking only soft drinks, but this didn’t stop me from entering into the spirit of things. The writer David Quantick recalls watching in amazement as I stood up and sang ‘Delilah’ to a room full of drunken revellers, while completely sober. I wasn’t going to let the opportunity of an audience go to waste.

I went to bed around one or two in the morning, bagging a mattress that someone else had already claimed with the placing of their holdall on the pillow. If they were going to stay up this late at night, making a noise, then they didn’t deserve a bed. I tried to go to sleep while the party carried on along the corridor, eventually nodding off around four o’clock, and waking again after a rejuvenating three hours’ sleep at seven. It was quiet now, a little too quiet, and I wandered out of the bedroom, past an unidentified body in the other bed, and along to the living room. Here I found, to my horror, assorted corpses asleep on sofas, chairs, a table and the floor. It looked as though a friendly genocide had occurred while I slept. Around the window some curtains had managed to come free of their mooring and now lay defeated on the carpet.

I think it was the sight of the curtains that did it.

I like fun as much as the next man, but when that fun involves a blatant disregard for the welfare of curtains or soft furnishings in general, it’s time to stop. I immediately got dressed, grabbed my bag and left. I walked briskly through the fresh August morning into the centre of Edinburgh and checked in at the Balmoral, a lovely five-star hotel with splendid views of the castle. Within half an hour I was reclining by the pool in my fluffy white robe, enjoying a breakfast of smoked salmon and scrambled eggs. This was my home for the remainder of the trip.

A few weeks had passed since Julia had handed the tape over to Steve. I was impatient to know what he thought of it, so I set about contriving a spontaneous random encounter with the King of Comedy. After another recording of

The Treatment

and an alcohol-free spell in the BBC Club, I wandered over with a friend one Friday night to the pub that I knew the cast of ‘The Man Who Thinks He’s It’ frequented after their curtain had come down. I planned to chat to Julia for a while until Steve joined us, at which point I’d casually mention the tape and wonder out loud if he’d had a chance to see it? I hoped that this would be enough to prompt a positive response and subsequent career enhancement.