Small Man in a Book (41 page)

Read Small Man in a Book Online

Authors: Rob Brydon

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

Well, quite a shock [PAUSE], they’ve all been shot. They had a virus, Herpes … Simian Herpes B. Uh, don’t know what they’ve been getting up to. I’ve had a virus, umm, not one like that, and I’m all right, I’m still standing. [PAUSE] Imagine that, ‘What is it, doc?’ ‘It’s a virus, Keith’ ‘What are my chances?’ ‘Well, if you start running now, pretty good.’ [HE MAKES THE GESTURE OF SHOOTING A RIFLE WITH HIS BISCUITS] Dear me …

Music plays a big part in the series. Hugo and I would raid our respective record collections, searching for the perfect choices, settling eventually on Slade, Bruce Springsteen, Tom Jones, Catatonia, the Bee Gees and Radiohead. With his brilliant editor, Graham Hodson, Hugo did a superb job in the edit. Creating an entirely distinctive look and feel for the show, he paced the stories wonderfully. He also did great things in the dub, very subtly manipulating the sound to enhance the narrative.

It was a great advantage that

Marion and Geoff

was spread out over ten episodes; it gave a chance for the word-of-mouth factor to build on the show, and build it did. Slowly at first, then slowly but surely, until it seemed as though everyone was talking about it. The critical response was exceptionally good from the start.

The Times

said it was ‘a beautifully judged tightrope act both in the writing and in the delivery … like an Escher drawing’.

The Sun

considered it ‘unmissable’, the

Mirror

felt it was ‘bleakly funny and achingly poignant’, and the

Telegraph

‘brilliant’.

In London’s

Evening Standard

, Pete Clark declared it was ‘the funniest British comedy effort for years, and it is also the most heartbreaking … a

Madame Bovary

for our times …’

Andrew Billen in the

New Statesman

called it ‘a work of art’.

Wow.

This response was more than I could have hoped for, and I was quite taken aback by the sudden attention and praise. I began to have a sneaking suspicion that I might have

arrived

, finally. While this was going on, Julia and I were often holed up in a windowless room on the South Bank in the edits for

Human Remains

with Matt Lipsey and his editor Charlie Phillips, agonizing over what should stay and what should go. In the episode

All Over My Glasses

, the original ending (a whole subplot involving the principal characters going off on a coach to see Texas at the NEC in Birmingham) was dropped. A bold and, frankly, unsettling decision.

We were told that

Human Remains

would begin transmission two weeks before

Marion and Geoff

had finished, and this bothered me. I was worried that all the work I’d been involved in for the last couple of years would be splurged onscreen and gone in the course of three months. As it turned out, it was the perfect way of showcasing my work. If anyone had thought that Keith was my one-trick pony then

Human Remains

, with its six very different couples, showed a range and versatility to put those suspicions to rest. The critical response was again fantastic, with

The Times

saying, ‘Rob Brydon and Julia Davis, who demonstrate a level of invention, observation and sheer versatility that defies comprehension … This is extraordinary television, so effortless and inexplicable that it is touched with comic genius.’

Affirmation, vindication, validation – these are all good words to describe how I felt. But along with my sudden notoriety came an unsettling new experience. Most people go through life hearing about themselves only what is said to their face; it’s very rare that anyone will come up to you and offer a disparaging comment with regards to your appearance. Once I began to be written about, this all changed, especially in the broadsheets – where a profile piece inevitably contains a degree of psychoanalysis for good measure. I was genuinely surprised, albeit perhaps a little naively, when so many of the writers who interviewed me would then include in their piece a comment or two on my appearance. As more and more articles were published, a theme began to emerge.

The

Observer

told its readers of my ‘sorrowful brown eyes and lugubrious features’.

Jasper Rees in the

Evening Standard

saw me as ‘a wiry Welshman with a long thin knife of a face’.

The

Daily Express

opined that I was ‘deadpan and tombstone featured’.

Jasper Gerrard, in the

Sunday Times

had given the subject considerable thought.

So does he have five-star potential? His appearance is utterly ordinary. Women would probably consider him boy-next-door crumpet, were it not that he is saved from any hint of matinee idol looks by his bad complexion.

Ouch!

The first year of the new millennium was coming to an end. And so too, it seemed, was my era of terrible job after terrible job. Everything had changed; I felt now as though I was on a wave, and all I had to do was ride it. After becoming used to a life of rejection letters, returned VHS cassettes thudding on to the doormat and a phone unable to make a call that could stretch beyond a secretary, I was suddenly receiving invitations to events here, there and everywhere.

One such invitation was to a party being thrown by the BBC to celebrate something or other relating to Light Entertainment. It was held in one of the large studios at Television Centre and was full of the great and good of the day. It was the first of many occasions when person after person seemed to want to come along and congratulate me on

Human Remains

and

Marion and Geoff

– I of course was only too happy to receive their praise. Early in the evening, through the throng of besuited bodies, I spotted Ronni Ancona coming towards me. I had met her some years earlier, while making the pilot

The Strip Show

for Channel Four, since when she had gone on to the BBC and great success with Alistair McGowan on

The Big Impression

. I had noticed her earlier across the room, talking to Ronnie Corbett and Ronnie Barker, in the process effortlessly forming a new comedy team, the Three Ronnies. Knowing how big a fan I was of the two, she offered to introduce me.

Ronnie C., all tartan-trousered warmth and charm, told me how much he’d enjoyed

Marion and Geoff

. I returned the compliment and gushed over him (probably a little too much), telling him how not just I, but my whole family, had loved his work over the years and how I had performed some

Two Ronnies

gags at school just before the world premiere of

Star Wars

onstage.

I wondered whether Ronnie Barker was aware of my work, and what he might have thought of it?

Ronnie C. introduced us: ‘Ron, this is Rob Brydon.’

Mr Barker looked over at me quizzically, his eyes narrowing. ‘Ah, you’re the chap who does that

Human Remains

.’

‘Yes …’

There was a pause.

‘I saw four of them.’

‘Right …’

There was another pause.

I stood waiting. Was he going to give me a compliment to add to my list? Surely he was; why else would he have brought it up?

He thought for a moment, before offering: ‘You should tell the girl that does it with you, she shouldn’t always play dowdy.’

And that was it.

But there was one more treat in store, a cherry on the cake of my success, when I discovered that I had been nominated for the Best Newcomer category at the British Comedy Awards. I was thirty-five years old; I had watched the awards every year since their inception, sitting on my sofa, sure that I would never be a part of it. How could I be? It was another world. I particularly remembered seeing Steve sweep the board with three awards just two years ago. It had seemed to me then like something from another universe.

The nomination was for

Marion and Geoff

and I wanted very much to win. The awards at that time took place at the ITV London Television Centre on the South Bank, just up the road from the National Theatre where, all those years ago, I had seen Anthony Hopkins in

Pravda

while on the college trip. It was also not far from the editing suite where, just weeks earlier, we had been arguing over

Human Remains

.

It was a good year, in which Alan Bennett won the Lifetime Achievement Award. When I was at college, there was a video library and each week

The South Bank Show

would be recorded and added to the shelf. I would often sneak in, between classes, and take out the show devoted to Bennett’s

A Private Function

and watch it again and again. Now here I was at the same ceremony as him, potentially winning an award on the same night. Victoria Wood was given the Writer of the Year prize. I had watched her stuff for as long as I could remember – Julia and I were both influenced by her when writing

Human Remains

, and Duncan Preston banging his head on the boom microphone in

Acorn Antiques

is one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen – and now here she was in the same room.

When the moment for the Best Newcomer category arrived, Jonathan Ross turned to introduce the presenter and I remembered how I’d interviewed him down the telephone line on Radio Wales aeons ago as he burst on to the scene with

The Last Resort

. Was I about to share the stage with him? Mum and Dad were watching the broadcast live, back home in Baglan, as the guest presenter took to the stage. It was Steve Coogan – a good sign, surely? He read the nominations, some clips were played, and then he opened the envelope.

Time stood still.

I prepared my magnanimous loser’s face.

And the winner is

…

Rob Brydon

.

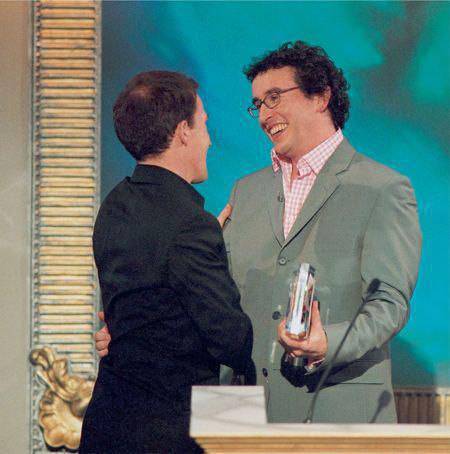

Winner of the Best TV Comedy Newcomer 2000 at the British Comedy Awards. ‘The student becomes the master.’

Unless you’re reading this, Steve, in which case, ‘The Best Day of My Life.’

That was the first award; the next year I returned and won the Best Actor Award for

Human Remains

. In the meantime, Julia and I both won Royal Television Society awards,

Marion and Geoff

won the

South Bank

Award for Best Drama and a Broadcasting Press Guild of Great Britain award.

Human Remains

was awarded Best Comedy at the Banff International Festival in Canada, beating

Frasier

and

Friends

in the process.

It felt good.

It also felt a little unreal. Had I really crossed the divide? And, if I had, would I be able to stay on this new side – where, I have to say, the view was much nicer. As I did the round of interviews and photographs that always follow the receipt of an award, I remembered the words Jimmy Savile had spoken to James Lovell and me all those years ago, at St David’s Hall in Cardiff, after we’d just performed our first paid gig.

‘It’s very hard to get to the top in this game, but it’s a damn sight harder staying there.’

Was he right?

I was about to find out.

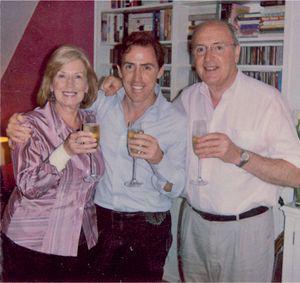

With Mum and Dad, celebrating my success at the British Comedy Awards.

Epilogue

Six years later, I was sitting on a bench looking out onto the water at Manly, one of the many glorious beaches that Sydney has to offer. I was in Australia for the second time, filming the second and, as it would turn out, last series of

Supernova

, a lovely, silly show that I made for the legendary Beryl Vertue and her Hartswood production company. I was eating fish and chips, and sitting next to me was James Corden; we’d stayed in touch after

Cruise of the Gods

and had hooked up in Sydney, where he’d found himself as part of the world tour of Alan Bennett’s

The History Boys

. They’d already been to Hong Kong and New Zealand, and after Australia would go on to win a record number of Tony awards on Broadway.

We were talking about a new project,

Gavin and Stacey

, that James was writing with my old school chum Ruth Jones. The two had met while filming the ITV series

Fat Friends

and had come up with the idea of a one-off film set at the wedding of an Essex boy and a girl from Barry, the seaside resort in South Wales.