So Many Roads (16 page)

Authors: David Browne

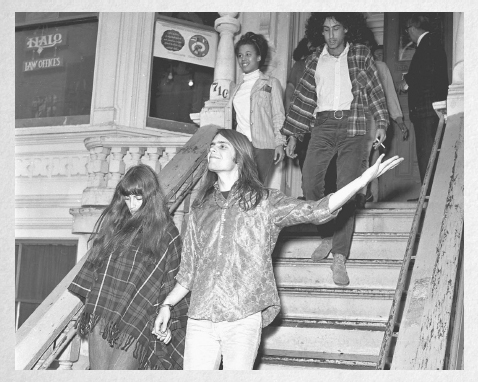

Whether the music had a steady, tick-tock consistency or not, some of the hundred or so people roaming around inside the Big Beat were dancing. One was Lesh's new female friend, Rosie McGee. Born in Paris, McGee had relocated with her family to San Francisco when she was young. By the strangest of coincidences, she'd been working as a secretary at Autumn Records the day the Dead had their audition, although she barely remembered them, given how quickly the recording had gone down. Always a stylish dresser, she'd been sent home one day from her job in an ad agency when she wore knee-high go-go boots to work; her bosses deemed it unprofessional attire. In contrast, the world of the Dead and the Acid Tests offered her a sense of liberation and community.

Before she'd left for the Big Beat, McGee made Lesh promise to stay with her all night; she didn't want to be left to her own stoned

devices, and he agreed. Certainly Lesh was unlike anyone McGee had known. In honor of the stick figure created by the advertising world to market the electricity industry, he'd been dubbed Reddy Kilowatt, and to McGee the nickname more than fit Lesh. With his jittery energy, he walked in a staccato manner (years later she'd be reminded of him when watching Kramer on

Seinfeld

), and he didn't seem to climb out of her car so much as jump out of it. “He was very electric, very kinetic, like he'd stuck his finger in a socket sometimes,” she says. “He was not a laid-back kind of guy. He was always jumping up, that live-wire stuff.”

By comparison, Garcia struck her as laid back and slower moving, yet the two men seemed to complement each other. More than once McGee saw Lesh and Garcia huddle and plunge into deep conversations about an arcane music topic, leaving everyone around them puzzled. “Everyone else would think, âWhat the hell are they talking about?'” McGee says. “But they would really be into some sort of exploratory discussion. They were both fearless, and it was all just one big experiment.”

For the Dead that night momentous things would occur even when they weren't playing. At one point in the evening they took a breakâwhatever that meant in the context of an Acid Test, which never had anything resembling a scheduleâand made their way to the bar. With that Scully made his move, walking over and introducing himself. He said their mutual acquaintance Owsley had suggested he become their manager. They responded with varying degrees of skepticism and bemusementâ“smart-alecky,” Scully saysâbut Garcia shook Scully's hand in what struck Scully as a genuine way. The surly looking organist, whom Scully soon learned was nicknamed Pigpen, told Scully he thought “Rock” was a “cool handle.” Nothing would be firmly decided on for a few months, but the basis of a working relationship was struck.

During one of the night's breaks Garcia went outside with Kaufman for a time out from the craziness inside. Soon after, the police arrived. Because Kesey had been busted for pot at La Honda the previous April, no one wanted to attract any unwarranted attention. According to Mountain Girl, the Kool-Aid being dispensed was intentionally low dose. “We weren't trying to create too big of a stir,” she says. “You had to drink five or six cups to really launch.”

Garcia and Kaufman watched as the squad car pulled into the Big Beat parking lot and a policeman stepped out and headed their way. “You could tell he was walking over with an attitude,” Kaufman says. “He had a serious law-enforcement vibe.”

Anyone else might have acted uptight or defensive, but Garcia radiated the opposite attitude; the people-handling skills he'd learnedâperhaps from watching his mother working at her barârose to the fore. As Kaufman watched, Garcia charmed the cop in only a few sentences, and the officer, suddenly less agro than he'd first been, simply said, “Uh, okay,” returned to his car and drove away. Reflecting back on Garcia's modus operandi, Kaufman says, “It was like watching someone do this beautiful martial-arts move where someone comes in with an energy and you dance with it and turn it around and off it goes.” When the cop drove off, all Kaufman could say to Garcia was, “How did you

do

that?”

Garcia had one last, enduring gesture. As the cop was leaving, Garcia took off the hat he was wearing and genially said, “Trips, captain,” which Kaufman interpreted as shorthand for “Have a good trip.” (According to Kaufman, the often-reported legend in which Garcia said “Tips, captain”âmeaning a tip of the hatâis incorrect.) Back inside the Big Beat, Kaufman relayed the story to Kesey, who so loved Garcia's comment that he flipped the words around and came up with Garcia's new nom de Prankster, Captain Trips. (Everyone had a nickname: Babbs, for instance, was “Intrepid Traveler.”) In the course of

two breaks the Dead had a potential manager and a nickname for one of their front men.

As dawn approached, the Acid Test at the Big Beat began gravitating back down to earth. The Warlocks and the Pranksters started packing their instruments, movie projectors, strobe lighting, and whatever else they'd each dragged along. Everyone, even those still flying on the unorthodox Kool-Aid, straggled into the chilly night to make their way back home.

The Acid Tests had few rules, but one of them decreed that everyone had to stay put until the Test ended in the early morning hours. Prolonging the communal group vibe was one reasonâit was comforting to find so many similarly minded oddballs in the Palo Alto areaâbut personal safety was equally tantamount. “It was not good to be high and out wandering by yourself,” says Babbs. “You wanted to stay in the scene where it was safe, with the people who were with you.” In her car, McGee, along with Lesh, both still tripping, turned on the heater and watched the ice crystals on the windshield meltâwhich, in their state, seemed like the most mesmerizing thing they'd ever seen.

The Acid Test at the Big Beat would be neither the last nor largest of those gatherings. In the months ahead others would be held in San Francisco, Portland, and down in Los Angeles. The setups would be similar. Once sound systems, projectors, microphones, and whatever else were installed, everyone was told to leave the building, re-enter, and pay the admission. Each Acid Test would add its own lore and yarns to the legend: dazed Testers wandering out into the streets of LA, huge garbage cans filled with dosed Kool-Aid, Lesh and Owsley conspiring about sound systems, Garcia and Mountain Girl sweeping up, Pigpen uncharacteristically asking Swanson to dance. Delays would be added to the tape recorders to make people's recorded voices

reverberate more around the rooms. In late January 1966 about ten thousand people would gravitate to the Trips Festival, a three-day-long, acid-driven freak-out at San Francisco's Longshoremen's Hall that presented some of the Big Beat contingentâthe Pranksters, the Deadâalong with poets, dancers, and Big Brother and the Holding Company, pre-Janis Joplin. No one, least of all anyone in the mainstream media, had witnessed anything like it. Far more than any of the earlier Acid Tests, the Trips Festival confirmed the existence of a growing movement. “In the Peninsula the people interested in something like that would be a few dozen or people who knew each other,” says Brand, who co-organized the Trips Festival. “But no one knew there were thousands of hippies.”

Compared to that gathering, the Big Beat Acid Test felt more like a test run than a major happening. “It was lighthearted fun that night,” Mountain Girl recalls. “Nothing too heavy happened.” She was rightâno arrests, no overdoses, no violence, no calamitiesâbut something did take place that night, a coming-together of disparate people, media, and chemicals that signaled a series of new beginnings for the Dead. By the time many of the band members drove off in Kreutzmann's station wagon, other aspects of their world had begun taking shape. They'd met not only their future manager but in the house were two women who'd play leading roles in their lives, McGee and Mountain Girl. (When McGee arrived at Lesh's home she discovered he had a girlfriendâwho didn't seem to remotely mind when McGee and Lesh kept walking into their own private back room.) Other attendees included Hugh Romney, the activist, satirist, and counterculture clown known as Wavy Gravy, and Annette Flowers, who would later work for the Dead's publishing company.

The Acid Tests were also where the Dead began finding their collective musical voice. They'd already begun reaching for the outer limits at bars like the In Room, but those gigs were straight-laced compared to the ones at the Acid Tests, where a song could last five minutes or

fifty. Neither traditional rock 'n' roll nor copy-cat blues or R&B, the sound was morphing into a mélange of it all, heavily dosed with free-form improvising. “We played with a certain kind of freedom you rarely get as a musician,” Garcia later told TV interviewer Tom Snyder about the Acid Test experiences. If Owsley was indeed at the Big Beat, as Scully recalls, they also spent additional quality time with the mad genius who would make a body-slam impact on their sound, finances, and sensibility. “He kept talking to me about how the better sound was low impedance,” Lesh says of conversations the two had at one Acid Test. “While we were waiting to start playing, it was all very loose. We were all peaking and ready to play. Bear and Tim Scully [Owsley's electronics-whiz friend] are down there on their hands and knees soldering a box to make it work with the system. It was like a bunch of guys watching someone work on a car.” When the system finally was up and blasting, Lesh was impressed with the bass, but the Dead only played for a few minutes and then, according to Lesh, Garcia “decided he wanted to go do something” and they stopped. But within a few months they would be playing through Owsley's sound system.

“Can

YOU

Pass the Acid Test?” read the fliers passed around by the Pranksters. Whether the locale was Muir Beach, Palo Alto, or southern California, the Acid Tests

were

endurance tests of sorts: if you were strong, wily, and open-minded enough, you could make it to dawn. (“It was pretty scary if you weren't expecting any of that stuff,” says Tim Scully, unrelated to Rock, who helped Owsley by building a mixing board, finding speakers, and ensuring the Dead's instruments didn't emit odious hums and noises.) The same mentality would now extend to the Dead. Theirs was an increasingly demanding world, one that would take stamina, thick skin, and the proper constitution to survive. “The Acid Test was the prototype for our whole basic trip,” Garcia later told

Rolling Stone

's Jann Wenner. He was right, and in more ways than he probably foresaw.