Soapstone Signs (2 page)

“Will my signs always come in dreams?” I say.

“Not always, but sometimes.”

“Where else will I get my signs?”

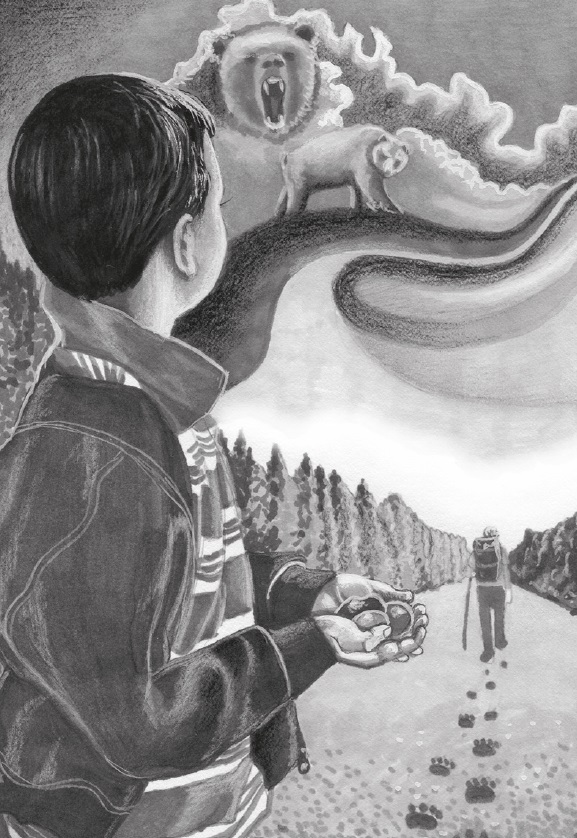

“Everywhere, from everything. Stay open to the world around you. You will learn to understand your signs.”

I work with Lindy all day. Mom brings us lunch by the riverbank. Tourists come to watch us. Some of them want to know what I am carving, but I just smile and say, “Work in progress.”

By suppertime, Lindy has made an owl and a walrus. He has already sold them, plus all the other ones he's made since he arrived at our lodge.

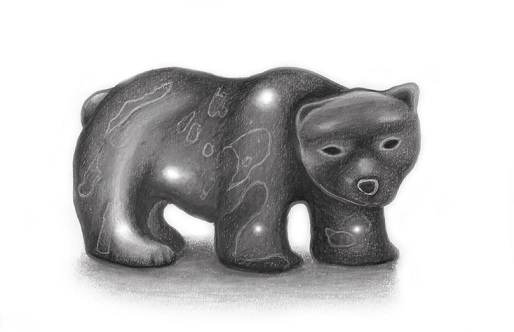

I finally finish my carving. The bear's head is crooked, and its neck too short. I have not left enough stone for one of the ears, and I've forgotten that bear cubs have small tails. I am feeling a bit ashamed of it. Then Lindy takes my stone carving in his hands. “That is a very good bear cub,” he says. I start to feel better.

My brother says it looks like roadkill. Dad looks it over carefully, then digs through his toolbox and gives me a rasp file for keeps. Mom asks my permission to put the bear cub in the display case, and I feel very proud.

Lindy stays for as many days as it takes to carve the soapstone pieces in his sack. Mom and Dad always invite him to stay longer, but he never does. Mom packs him some sandwiches. Dad lets me walk him down the tracks to the marker line that tells the train our stop is coming.

At the marker, Lindy stops and shakes my hand like I am a grown-up. He hands me his burlap sack. There are still three nice pieces of soapstone in it.

“I think you are going to be a very good carver,” he tells me.

“

Meegwetch

,” I say.

“Thank you also,” he says.

I watch him disappear to the south. I will practice listening to the stone. I will be ready for the signs. I will wait for the ice to break up on the river and for the geese to fly back home. Most of all, I will watch for Lindy to arrive again. When he does, I will show him my carvings.

Blueberries, Blackflies and Belugas:

A Summer Encounter

I saw

wapamegwak

from the school boat in the last week of school before the summer holiday. I'm sure I did, because sometimes beluga whales swim in from the bay to spend time in the river. But there was just a hint of them way off in the distance toward the bay. “There's the whales!” I yelled. Everyone looked, but no one else saw them. Some big kids said I was only seeing the whitecaps on faraway waves. They asked me on the way home where my “invisible belugas” were.

Lindy uses white stones called gypsum that he's found along the riverbank to carve beluga whales that the tourists love to buy. Except he would say “wapameg,” or “wapamegwak” for more than one. That's

beluga

and

whale

in one Cree word.

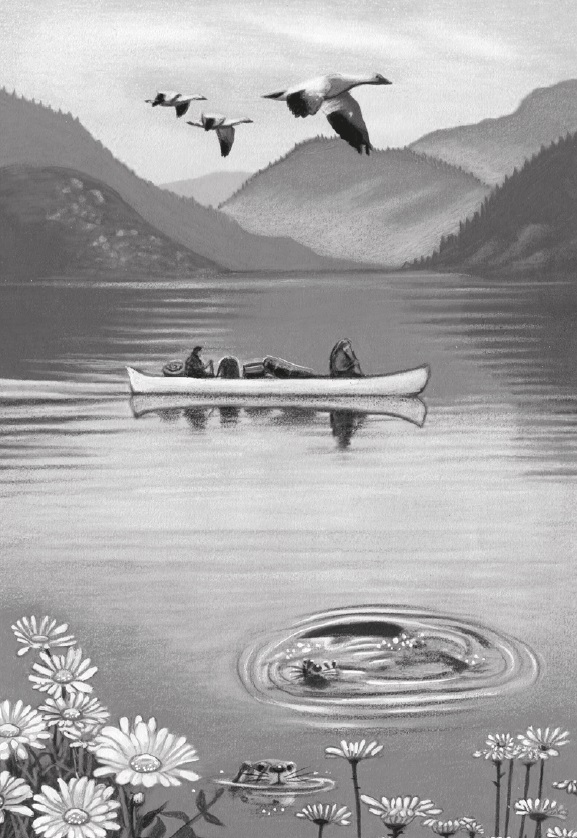

Every year after the blueberries come out, Mom paddles downriver and camps overnight. She usually goes alone so she can spend some special time remembering. When she gets home, it's blueberry bannock and pies for everyone. This year is different. She has invited me to go with her, and I am excited. I've been camping with the whole family but never just with Mom. We will pick some berries and make a campfire. If I am lucky, maybe I will hear some stories. But I am mostly excited because I know that wapamegwak are out there somewhere.

We make our journey in Mom's canoe. Mom's canoe is made of cedar strips and covered in white canvas. She takes very good care of it.

Mom and I have packed bannock mix, strips of smoked whitefish and some water. We have a first-aid kit, bedrolls and a small tent. She has also packed her rifle in case our camping gets interrupted by

wapask

, the white bear. I have never seen her take her rifle out of its cover, but Dad once told me she is a better mark than he is and that's one of the reasons he's so good to her.

I have packed one of the soapstone pieces from Lindy. I will be ready to start a new carving as soon as my signs and whispers tell me what is waiting for me inside the stone.

“What if we run out of food?” I ask Mom.

“Then we hunt and we gather. Food is all around us.”

“What if the fish won't bite?”

“Then we learn to be hungryâthat will make us better hunters.”

The blackflies are biting. “I wish there were no bugs!”

“Without the insects, there would be no blueberries or belugas,” Mom says. “The insects help turn the blueberry flowers into berries. They also act as food for the fish, and those fish go on to feed the belugas.”

“Okay,” I say, “but I wish the blackflies would just eat the blueberries instead of biting us.”

“Me too,” says Mom as she passes me some bug spray.

We paddle out onto the river. With the current flowing toward the bay and the tides pulling in the opposite direction, the river creates tiny “tut-tut” waves. The waves don't go one way or the other but lift straight up into tiny peaks and drop back down again. Little drops are left hanging in the air for a split second. If you listen, it sounds like the gentle

tut-tutting

of a hundred tongues. It's like the river is thinking but can't make up its mind about something.

I have tut-tuts in my ears and blueberries and blackflies in my thoughts. But mostly I'm thinking about belugas and keeping an eye peeled over the water. We are paddling to a place called an estuary, where the salt water of the bay and the fresh water from the rivers inland meet.

There is lots of time to think when you are paddling a canoe.

I think about being a human being, and how when I breathe the air I can feel the breath come in and out of me. I can feel the wind against my body, and I know that it is gravity holding me to the ground. I can see when it is light or dark, and I can feel when it is hot or cold or wet or dry.

Lindy taught me to use my senses to be aware of signs and messages from the world around me. I wonder about the beluga whales who breathe the air like we do, and I wonder about all the signs that they can feel, smell, taste, see and hear in the water.

I think about the fresh water from the river mixing with the salt water in the bay. And I think that must be an important sign for the whales.

I think about how belugas can see, hear, feel, smell and taste just like we can. But they also have an extra sense that lets them bounce sound through the water around them. This is how they know what else is in the water, like friends, food or danger. I think the belugas must know secrets about the water that people have not thought of yet.

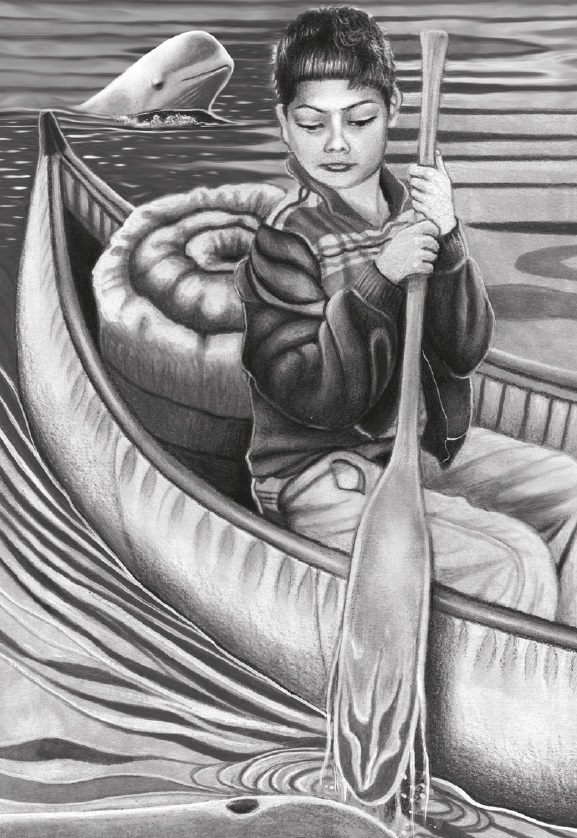

At first, I think we've paddled up beside a long gray river rock. Then I realize that the long gray river rock swam up beside us!

The wapameg is almost as long as our canoe and gently breaks the water beside us. I am tingling with excitement but do not feel scared.

I look up at Mom, who is paddling gently while the whale swims beside us. She motions for me to look across to where a bigger beluga is gliding slowly toward us. This whale is longer and wider, white like snow and floating as gently as a cloud in the sky.

“She is the mother,” my mom whispers as the big white wapameg comes slowly alongside. Little Wapameg must have separated and mistook the round white underside of our canoe for the mother's belly.

The small gray wapameg is sounding in trills, squeaks and clicks that we can hear from the water. Mother Wapameg answers in a voice of whistles and calls. It sounds like the little one is asking questions and the mother is patiently answering.

Little Wapameg gets close enough to brush the side of our canoe. Then the whale rolls slightly sideways so that one eye breaks the surface and looks up. Right up at me!

Little Wapameg's eye is big, wet and round. The color is a deep gray, nearly black, shimmering like a mirror and bottomless too. The eye shines like a polished carving stone. I feel Little Wapameg look at me and it's as if we are sharing all the wonder from inside both of us. I feel still and calm.

Mother Wapameg starts to move away from the canoe. She sounds a whistle and makes some clicking noises. Little Wapameg rolls back into the water, clicks in answer and moves slowly forward to catch up. I reach down and touch Little Wapameg on the backâthe skin is gray-blue and slippery smooth. The texture makes me imagine how the whale could be cozy and warm inside the cold water.