Soapstone Signs (4 page)

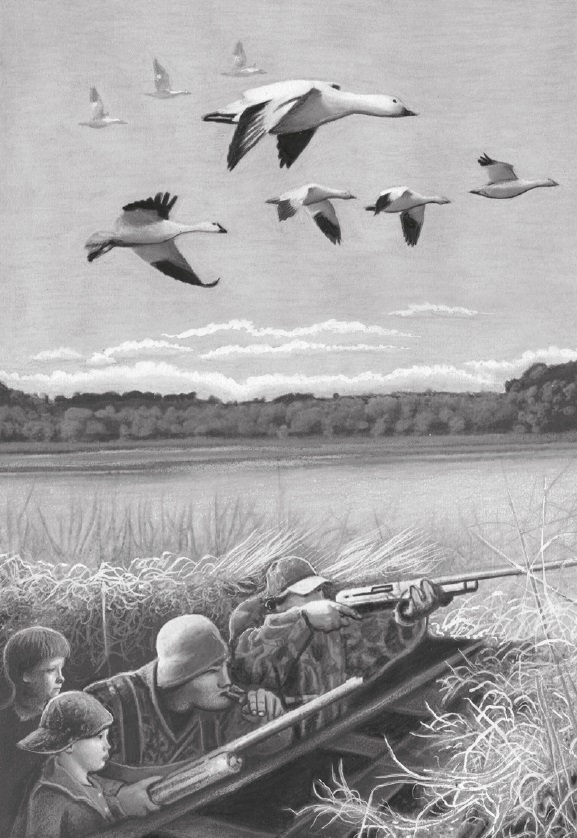

Geese appear like specks against the morning sky. Then wings, bodies and necks start to take shape. One swoops down, and Stan does not miss. Three more times he does not miss.

My brother and I are sent to collect the downed geese. We have to be fast and quiet. The geese are big, heavy and still warm as we try to gather them in our arms. Some blood trickles down my arm as I hurry back, and I have to look away.

Next, my brother takes his turn. Dad calls and a goose comes circling down. My brother shootsâbut too soon. The bird ruffles its feathers and swoops back up and out of sight.

“We'll try again,” Stan whispers.

On his second try, my brother misses again. He wants one so bad. He glares at me like he wishes I had a beak and feathers. Then, on his third try, he brings one down. My brother whoops so loud that Dad has to shush him, but the tension is gone and everyone is happy in the blind.

My turn comes, and I shoulder my gun. I hear Dad call. A far-off answer comes from the sky, and a speck turns to wings circling downward. I trace the bird and wait. The shot feels sure, just like the skeets did yesterday. I have butterflies in my stomach, but it's as if they are flying in formation.

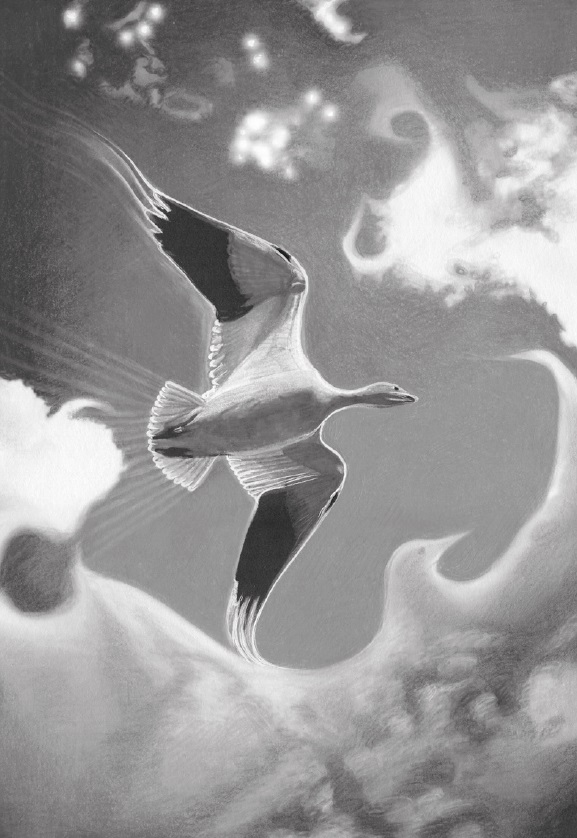

I watch the beautiful snow goose, thinking about its long journey across the world and back again. If I went all the way across the world, I would long to come home as well. I think about how it's just seeking food and safety before winter comes. And I think about how in springtime, when the snow goose flies back home, it will be a sign that Lindy will soon be here.

Something in me moves the gun barrel as I squeeze the trigger. The goose shifts in the air and flies up and away. I look behind me to where Stan is sitting. His face is lined up along my gun barrel, his head slightly tilted. His eyes meet mine in a questioning way. He knows I missed on purpose. I look away quickly. After that I reload, and Dad continues to make his calls. No more geese come down, which means the hunt is over for the day.

We return from the hunt. There will be no need to order fried chicken for tomorrow's community feast.

The next evening, geese and bannock cook slowly on sticks that lean over large fires. The air smells delicious and is full of laughter. Everyone is happy. It's the kind of happiness you feel when you have saved up your hunger on purpose.

On winter hunting grounds, the hunters eat first and the elders eat last, in case there is not enough food. At community feasts, the elders eat first and then the children. The hunters and cooks who provided the feast eat last. Everyone eats as much as they want.

The elders are served, and the children are called to line up for food. I start toward the line and feel a familiar hand, strong but gentle, on my shoulder. It is Chief Stan, wearing his eagle feather. He says that I will be served with the hunters today.

“Okay, Stan,” I sayâbut my voice is very small. I have not looked him in the eye since the hunt.

I stand with my dad, brother and all the other hunters while people line up to fill their plates. We stand proudly. Stan motions for me to be the first hunter to go to the serving tables, and the community claps and cheers. I have so many feelings fighting inside me that I do not want to look up. I do not feel very hungry.

One of the soapstone pieces that Lindy gave me is in my pocket, along with my rasp file. He won't be back until spring, but I have been wishing he was here. I want to ask him about when my signs and whispers tell me to do opposite things. After the feast I will walk down to the riverbank, where I can be by myself and begin to carve. Inside the stone, there is a snow goose in flight.

River Weasels:

A Winter Discovery

So far I have carved a bear cub, a beluga whale and a snow goose, and I am getting better at it. I have one more piece to carve before spring, when Lindy comes back to visit my family. I am excited to show him my carvings. I am open to signs so I can learn what is waiting for me inside the very last piece of soapstone.

Right now it is wintertime. We have lots of wintertime where I live. The ice on the river gets thick enough to skate on safely. Sometimes the wind clears off the snow and we can skate for just about forever. And around here, if it's winter, it's also hockey season.

Mom is a hockey nut, and she comes out to practice with us. She has this move she calls the “ol' dipsy-doodle,” where she pretends to pass but keeps the puck on her stick. She laughs every time she does it, and when we get tricked, we laugh too. But I am getting wise to it and even try it on my brother sometimes.

My brother and I play in the kids' league at the arena on Saturday mornings. This is our first year. We are rookies together.

Between shifts on the ice, the players sit on a long bench. Everyone comes in one door, sits on the bench and slides down toward the other door. That's how you know it's getting close to your turn on the ice again.

My brother and I stick together so we can be on the ice at the same time. We are almost the whole way down the bench when these two other bigger brothers come and push us. Then they take our turns. Some other kids on the bench laugh, and one says that river weasels like us don't belong there.

The coach doesn't notice right away. Then we get our turns again. My brother is so upset that he smashes his stick on the ice, and he gets put in the penalty box for doing it. When I am back on the bench without him, the same kids tease me, saying, “Aww, do you miss your big brother?”

I do miss him. But I will not show it. I try not to let the teasing take all the fun out of the hockey. I am learning that not all signs feel goodâsome are signs of danger.

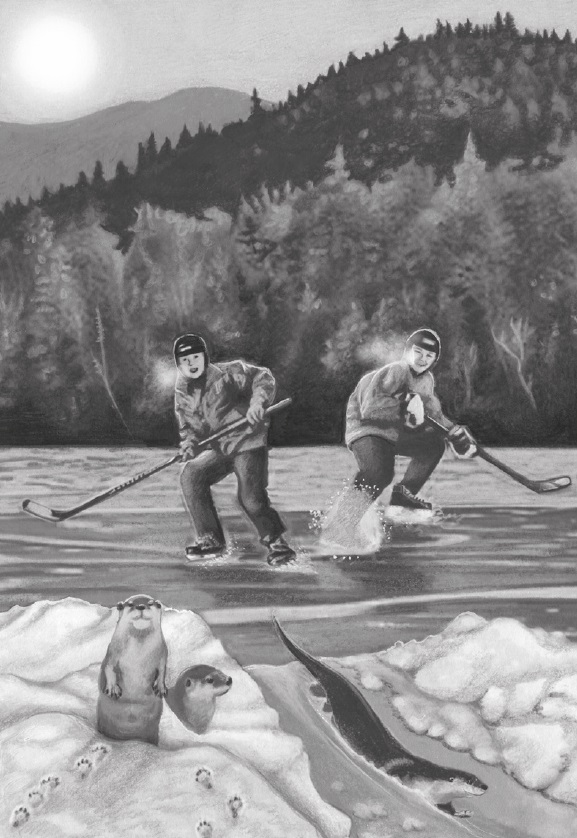

We still have our hockey stuff on when we Ski-Doo home, so we head right out onto the river rink for more. We pass the puck back and forth. I'm not sure if I want to go back to the arena. I think my brother feels the same way, because his passes are too hard and he keeps staring down at the ice. Trouble is, I really like hockey. And my brother is getting really good at it.

Mom and Dad are out skating with us. Dad has a stick, and he gets the puck and carries it way down the ice. We race after him in a mad scramble. Dad fires the puck and it goes whipping around the bend of the shore and out of sight.

We hustle around the bend and then come to a screeching halt. A romp of otters has made a slide on the snowy riverbank. When they see us come around the corner, they stop and look startled, just like we did. Then they start right back up with their fun.

The otters slide on their bellies, head first with their legs tucked under their bodies. They go whooshing out onto the ice, where they roll and wrestle. Their squeaky chitter-chatter noises sound like laughter. When they stop, they untangle themselves and race back up the bank.

Mom and Dad catch up to us and watch. Even when you're sad, it's hard to watch otters and not smile and laugh along. There are four of them in their family too.

The otters push their way into a spot near the bottom of the snow slide and disappear under the ice. I guess it must be their suppertime, like it is for us.

My brother and I skate up closer to where the otters were. There is a mess of crayfish shells on the ice and lots of otter footprints. There's also an icy line down the snow hill that their bodies made when sliding.