Read Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect Online

Authors: Matthew D. Lieberman

Tags: #Psychology, #Social Psychology, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience, #Neuropsychology

Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect (35 page)

BOOK: Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect

2.65Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Think about how amazing the brain is, and then consider that a huge portion of that amazing brain helps to make us more social.

Yet for a large part of our day, whether we are at work or at school, this extraordinary social machinery in our heads is viewed as a distraction, something that can only get us into trouble and take us away from focusing effectively on the “real” task at hand.

Chapters 10

,

11

, and

12

reveal how wrong this view is.

Almost everything in life can be better when we get more social.

If we retune our institutions and our own goals just a bit, we can be smarter, happier, and more productive.

The Price of Happiness

We all want a good life—to be happy and healthy.

Society at large has a huge investment in people being happy and healthy as well; happy and healthy people are more productive, get into less trouble, and cost society less money.

Philosopher Jeremy Bentham founded the Utilitarian school of thought on the notion of the

greatest happiness principle

, or the idea that the best society has the greatest amount of pleasure relative to its pains.

The big question—a question that has been asked for as long as we have been asking questions—is what makes for a happy and healthy life.

If we have been getting this wrong, we should all want to know so we can start getting it more right.

In 1989, more than 200,000 college freshmen were asked

about their life goals, and one goal stood out from the rest—to be well-off financially.

Perhaps these students had been reading Ayn Rand’s novel

Atlas Shrugged

, in which one of the characters declares that “money is the root of all good.”

Or perhaps they were just being sensible.

If Bentham is right about pains and pleasures, having piles of money is a great way to avoid physical discomforts and to

maximize access to life’s material pleasures.

Want to travel to exotic places and eat the world’s finest cuisines?

Want to go farther and orbit Earth from space?

You can do all of these things, but only if you’ve got the bank account to get you there.

There’s no question that making more money is valued worldwide and that it provides access to countless resources.

But does it make us happy?

Economists have been obsessed with this question

for several decades, in part because the income of individuals and nations was long taken as an objective indicator of their well-being, for it was believed that true well-being could not be directly measured.

This assumption in some ways may have led money to be seen by society as an end in itself, rather than as a means to an end.

Despite the presumption that true well-being cannot be directly measured, “happiness,” “life satisfaction,” and “subjective well-being” are actually measured quite easily.

All you have to do is ask people questions like “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?”

and people will tell you.

If you ask the same people today and a year from now, you will pretty much get the same answer from folks both times.

People have stable, reliable responses to this kind of question.

There are many ways to tackle the relationship between money and well-being, and economists seem to have tried them all.

The surprising conclusion of nearly every approach is that money has much less to do with happiness than we think it does.

Let’s begin with the one and only analysis that ever shows strong links between money and well-being.

If we look at a large number of countries

and for each nation get an average measure of well-being and get the nation’s average income level, these two factors will be correlated quite highly.

Countries with higher average income have citizens who report higher average well-being.

But this kind of analysis may not tell us very much because rich countries differ from poor countries in countless other ways.

Rich countries allow for more individual freedom, have better schools and health care, and have less corrupt judicial systems.

Gross domestic product may just be

a proxy for one or more of these other variables that might affect happiness more directly.

Let’s consider some of the other tests.

Researchers have also looked at the link between money and well-being within particular countries.

For instance,

happiness researcher Ed Diener looked at surveys of thousands of U.S. adults

who reported their subjective well-being and their income.

There was a statistically significant relationship between how much a person earned and how happy they were, but it was extremely modest.

Individuals’ income explained only about 2 percent of the differences in happiness across the sample.

And most of this relationship has to do with being below or above the poverty line.

If you are below the poverty line, every additional $1,000 you earn dramatically alters your well-being.

But once the basic needs are met, increasing income only adds the tiniest bit to well-being.

Some have suggested that the proper way to isolate the relationship between income and well-being is to look for changes in income over time.

For instance,

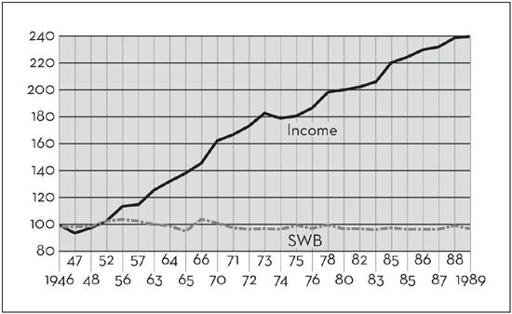

one study examined changing U.S. income levels between 1946 and 1990

and compared these to changing self-reports of well-being.

The results, shown in

Figure 10.1

, are striking.

Income, after controlling for inflation, more than doubled during this time, and yet well-being did not increase at all.

This effect, called the

Easterlin Paradox

for the economist who first discovered it, has been shown for many countries, but for none more dramatically than Japan.

Between 1958 and 1987,

real income increased 500 percent

and material comforts multiplied similarly (for example, car ownership grew from 1 percent to 60 percent).

Nevertheless, Japanese reported equal levels of well-being across these three decades.

I don’t know about you, but I find this all very disconcerting.

I work hard for my money, and I work hard to make more of it.

I do this because I know in my gut that if I can make more, my family and I will be happier.

This brings us to the last stop on the money train to happiness.

Some economists have tracked individuals across a decade or so to see if changes in their personal income level are associated with concomitant changes in well-being.

They aren’t.

Some people were making substantially more money at the end of ten years and some were making substantially less, but well-being was unrelated to these changes.

My gut says making more money will make me happier, but my gut is wrong.

Figure 10.1 Changes in U.S.

Income and Social Well-Being (1946 to 1989).

Adapted from Easterlin, R. A. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all?

Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization

, 27(1), 35–47.

Explaining the Paradox

I shouldn’t be alone in my frustration at this point.

The vast majority of people indicate that making more money is one of their primary life goals.

We don’t do this for the heck of it.

We do it because we believe it will give us a better life in the end.

Yet study after study reaches the same conclusion: it won’t.

We have been barking up the wrong tree.

How could we, as a society, have gotten this so wrong for so long?

What are we missing to end up so misguided in our theory about what will make us happy?

After the lack of a relationship between money and happiness came to light, economists and psychologists each offered sensible explanations of the missing relationship between money and happiness.

Psychologists pointed out that humans

have the tendency to adapt to new circumstances, whether they are good or bad.

This is called

hedonic adaptation

, and in many situations, it helps protect us from staying depressed forever over negative events.

Unfortunately, the same mental machinery keeps us from staying elated after positive events.

The most famous example of this is the case of the major lottery winners who were contacted some time after winning.

They reported being no happier

than individuals from the same communities who had not won.

Economists generated a second explanation focusing on the context in which one’s income is considered.

They suggested that the problem is that we focus less on our absolute income and purchasing power and more on how much we are making relative to those around us.

This

relative income

argument suggests

that earning $50,000 a year in a neighborhood where most people earn $30,000 a year could make us happier than earning $100,000 a year and having neighbors who earn $200,000 a year.

Missing Social

Things are even worse than I’ve portrayed them, at least in the United States.

Not only is increasing income not associated with increased well-being over the past several decades—but well-being has actually decreased over this time period.

Sensitivity to relative income definitely accounts for part of this reduction in happiness, but it’s not the whole picture.

Something else is going on that can’t be explained by these kinds of factors.

In the book

Bowling Alone

, Robert Putman

first put his finger on what was missing in all of these analyses: social.

Putnam and those who have followed him have put together a number of variations on the same two-step

theme.

First, social factors substantially contribute to subjective well-being and life satisfaction.

Second, in modern nations like the United States, these social factors are in decline.

Let’s take these in order.

Economists use terms that sound like economic indicators, such as

social capital

and

relational goods

, to talk about a variety of social factors.

These include being married, having friends, the size of one’s social network, whether people join social organizations (such as bowling leagues), and trust in various societal institutions.

Pretty much any way economists examine

these social factors, they (unlike income) end up being significantly related to well-being.

One study compared the impact of income

and social connections on well-being and found that social factors had a more positive impact on well-being than income, once relative income effects were considered.

Just how much are the social aspects of our lives worth in terms of our well-being?

Multiple studies have managed to put a dollar value on them, determining how much more money you would need to make in order to achieve the same increases in well-being.

In one study,

volunteering was associated with greater well-being

, and for people who volunteered at least once a week, the increase in their well-being was equivalent to the increase associated with moving from a $20,000-a-year salary to a $75,000-a-year salary.

A second study found that across more than 100 countries,

giving to charity is related to changes in well-being

equivalent to the doubling of one’s salary.

Another study found

having a friend whom you see on most days,

compared to not having such a friend, had the same impact on well-being as making an extra $100,000 a year.

Being married is also worth an extra $100,000, while being divorced is on par with having your salary slashed by $90,000.

Just seeing your neighbor regularly is like making an extra $60,000.

By far, the most valuable nonmonetary asset researchers examined was physical health, with “good” health compared to “not good” health equivalent to about a $400,000 salary bonus.

That might

seem crazy, but if you were not in good health, how much money would you be willing to give up to be in good health again?

The reason I mention health is that

social factors are also huge determinants of physical health

.

Thus social factors determine well-being directly and, because they bolster health, provide an additional indirect route to well-being.

The good news is that building more “social” into our lives is very cost-effective—getting coffee with a friend, talking to a neighbor, or volunteering won’t make your wallet light and could significantly improve your life.

The bad news is that as a society, we’re blowing it.

Over the last half-century, there has been a steady decline in nearly all things social apart from social media.

People are significantly less likely to be married today

than they were fifty years ago.

We volunteer less, participate in fewer social groups

, and entertain people in our homes less often than we used to.

To me the most troubling statistics focus on our friendships.

In a survey given in 1985,

people were asked to list their friends

in response to the question “Over the last six months, who are the people with whom you discussed matters important to you?”

The most common number of friends listed was three; 59 percent of respondents listed three or more friends fitting this description.

The same survey was given again in 2004.

This time the most common number of friends listed was

zero

.

And only 37 percent of respondents listed three or more friends.

Back in 1985, only 10 percent indicated that they had zero confidants.

In 2004, this number skyrocketed to 25 percent.

One out of every four of us is walking around with no one to share our lives with.

Being social makes our lives better.

Yet every indication is that we are getting less social, not more.

BOOK: Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect

2.65Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Other books

THUGLIT Issue Twelve by Marks, Leon, Hart, Rob, Porter, Justin, Miner, Mike, Hagelstein, Edward, Garvey, Kevin, Simmler, T. Maxim, Sinisi, J.J.

The Queen`s Confession by Victoria Holt

Backlash by Nick Oldham

Jubilee Hitchhiker by William Hjortsberg

Guarding Miranda by Holt, Amanda M.

Risky Undertaking by Mark de Castrique

The Executor by Jesse Kellerman

Home Before Midnight by Virginia Kantra

The Arcanum by Janet Gleeson

Double Tap by Lani Lynn Vale