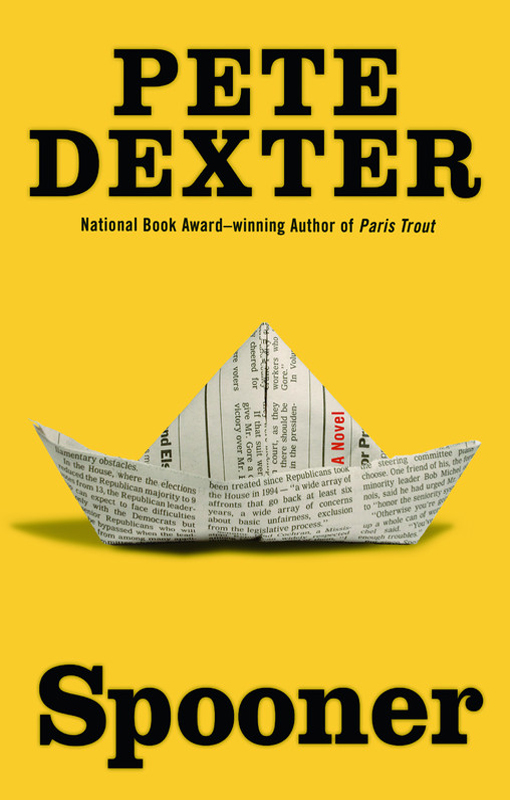

Spooner

Paper Trails

Train

The Paperboy

Brotherly Love

Paris Trout

Deadwood

God’s Pocket

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are

used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Copyright © 2009 Pete Dexter

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written

permission of the publisher.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

HachetteBookGroup.com

.

www.twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First eBook Edition: September 2009

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-446-55816-7

CONTENTS

For Cousin Bill and Mrs. Dexter

ONE

S

pooner was born a few minutes previous to daybreak in the historic, honeysuckled little town of Milledgeville, Georgia, in

a makeshift delivery room put together in the waiting area of the medical offices of Dr. Emil Woods, across the street from

and approximately in the crosshairs of a cluster of Confederate artillery pieces guarding the dog-spotted front lawn of the

Greene Street Sons of the Confederacy Retirement Home. It was the first Saturday of December 1956, and the old folks’ home

was on fire.

The birthing itself lacked cotton-picking, and grits, and darkies to do all the work, but otherwise had the history of the

South stamped all over it—misery, besiegement, injustice, smoke enough to sting the eyes (although this was as invisible as

the rest of it in the night air), along with an eerie faint keening in the distance and the aroma of singed hair. Unless that

was in fact somebody cooking grits.

As we pick up the story, though, three days preceding, the retired veterans are snug in their beds, and Spooner is on the

clock but fixing to evacuate the premises no time soon. Minutes pool slowly into hours, and hours into a day, and then spill

over into a new day and another.

And now a resident of the home dozes off with a half-smoked Lucky in his mouth, which falls into his beard, unwashed since

D-day or so and as flammable as a two-month-old Christmas tree, and it all goes up at once.

While back in Dr. Woods’s office, Spooner is still holding on like an abscessed tooth, defying all the laws of the female

apparatus and common sense—not that those two spheres are much overlapped in the experience of the doctor, who is vaguely

in charge of this drama and known locally as something of a droll southern wit. But by now Dr. Woods, like everyone else,

is exhausted as well as terrified of Spooner’s mother Lily, and no droll southern wittage has rolled off his tongue in a long,

long time.

It’s a stalemate, then, the first of thousands Spooner will negotiate with the outside world, yet even as visions of stillborn

livestock and dead mares percolate like a growling stomach through the tiny band of spectators, and Dr. Woods discreetly leaves

the room to refortify from the locked middle drawer of his office desk, and Lily’s sisters, who, sniffing tragedy, have assembled

from as far off as Omaha, Nebraska, but are at this moment huddled together at the hallway window to have a smoke and watch

for jumpers across the street, Spooner’s mother rolls out of bed on her own and gains her feet, and in those first vertical

moments, with one of her hands clutching a visitor’s chair for balance and the other covering her mouth against the possibility

of unpleasant morning breath, she issues Spooner, feet first and the color of an eggplant, the umbilical cord looped around

his neck, like a bare little man dropped through the gallows on the way to the next world.

As it happened, Spooner was second out the door that morning, a few moments behind his better-looking fraternal twin, Clifford,

who, in the way these things often worked out for Spooner’s mother, arrived dead yet precious as life itself, and in the years

of visitation ahead was a comfort to her in a way that none of the others (one before Spooner and two further down the line)

could ever be.

And was forever, secretly, the favorite child.

D

ue to problems of tone and syntax, not to mention good taste (how, after all, are you supposed to fit a regular baby and a

dead one into the same paragraph without ruining it for them both?), Spooner’s birth was left out of society editor Dixie

Ander’s regular weekly account of local comings and goings in the

Milledgeville World Telegraph

, and the birth certificate itself was subsequently tossed by Miss Ander’s unmarried first cousin, Charlotte Memms, who at

this point in her career had worked without oversight or supervision for thirty-six years in the Baldwin County Office of

Registrations and Certificates, filing and discarding documents as she saw fit. There was a soaking rain on the day that news

of Spooner’s birth arrived on her desk, and the afternoon before one of the Stamps niggers from down in the Bottoms had driven

his turkey truck into town, parked in Miss Charlotte’s just-vacated spot in the courthouse parking lot and promptly got himself

arrested inside, sassing the county clerk over the poultry tax, and Miss Charlotte saw that truck full of turkeys in her regular

spot when she came to work in the morning, half of them drowned, and decided then and there that she’d had enough—she was

tired of being taken for granted and tired of people without manners—and so it happened that until the census board caught

up with her the following year, the rule of thumb in Baldwin County was that you did not get born here without references.

Which is not meant to leave the impression that the birth went unrecorded. In Lily Spooner’s log of unspeakable ordeals, it

was never lower than number five, and Lily, it could be said, had made her bones in matters of the unspeakable and knew the

real goods when she saw it. And was wolfishly jealous of what was hers. And had Spooner’s brother only hung around a day or

two, long enough to break bread, as they say, the tragedy might very well have made it all the way to the top.

Even so, no one even casually of Lily’s acquaintance thought of suggesting that he appreciated what she had endured, certainly

no doctor or relative, and if some afternoon a month or a year after the event, perhaps in the throes of an asthma attack,

she suddenly compared the grittiness of birthing twins—she lost one, you know—to a battlefield amputation, who was going to

argue the point? You? Are you crazy? She said things like this just daring someone like you to say something like that. Daring

you to say anything at all. And you wouldn’t, not even if you were standing there in the uniform of the United States Army,

sprouting ribbons and medals on your chest like rows of porch pansies and peeking over the foot of her bed on stumps. You

wouldn’t, because hanging over this opera was the strange possibility that she

had

suffered beyond what you could understand, or imagine, and to demonstrate her vantage in the field, she could easily refuse

food for a week and simply live off bad luck and misfortune. And how would you feel then?

But hold on a minute, you’re thinking, sustain life on nothing but bad luck and misfortune?

To borrow one of Lily’s many lifelong expressions which always ran an involuntary shudder through Spooner, you darn tootin’.

Bad luck and misfortune. You probably have to see it for yourself to see it, but the model is there in any grade school history

book, in the carefree wanderings of our predecessor, the migratory Sioux, happy as a clam out on the prairie, employing every

last bit of his buffalo right down to the molars. Which is the way you live off misfortune and bad luck, using

everything

, the same way you live off the pitiful salary paid to public schoolteachers. Waste not, want not.