Stalin's Daughter (37 page)

Authors: Rosemary Sullivan

Meanwhile, the

New York Times’

reporter in New Delhi, Tony Lucas, had been piecing together the story. Through anonymous sources, he discovered that, in the early hours of March 7, Svetlana had flown out of India in the company of someone said to be the US Embassy second secretary, Robert Rayle. By checking the passenger manifest for all flights out of New Delhi, he concluded that Svetlana and her escort were in Rome. Obviously he wasn’t the only journalist to do so.

At three a.m. on Friday, Rayle and Svetlana were awoken with the news that the international press had tracked them down to Rome. The Italians wanted them gone. They waited for the next five hours to be moved out. Finally they left for the airport under guard and were just about to board the 3:00 p.m. flight to London and on to America, when Rayle phoned a friend at the embassy to say good-bye. “Don’t get on the plane,” his colleague said. The Swiss had come through.

12

They were to meet the Swiss consul at the airport at 8:00 p.m. to get Svetlana’s visa. A young woman from the US Embassy brought her a dark green raincoat; dark sunglasses, which she refused to wear; and a small red suitcase for her few clothes and her manuscript. Because she was not legally in Italy, she could not step on Italian soil and so could only glance at the passing sights of Rome from the car window as they drove to the airport, she and Rayle laughing and singing “Arrivederci, Roma.”

13

Svetlana must have thought she was in a film. Obtaining her visa turned into a car chase. Two cars, she in one and the Swiss consul in the other, circled the flowerbed in front of the airport for what seemed ages until finally she was transferred to the other car. A secretary with a bottle of ink and a rubber stamp stamped her visa, joking about the undercover operation. She returned to her car. But Swissair Flight 615 to Geneva was four hours late. Svetlana and Rayle retreated to the safe house to wait.

Then the movie became a farce. When she and Rayle returned to the airport, international journalists and photographers were swarming the terminal. A TV film truck had managed to turn its floodlights on the departure gate. Afraid that Rayle and Svetlana might be photographed together, the Italians insisted they board the plane separately.

Rayle slipped through immigration and onto the plane easily,

but when the car carrying Svetlana arrived at the gate, it was swarmed by paparazzi, and the car turned back. A new plan was hatched. Svetlana would be smuggled to the plane in one of the small tractors that pull the baggage carts. She squeezed in behind the nervous driver.

But as the tractor approached the plane, an Italian official rushed toward it. There were too many reporters.

Back, back

, he gestured wildly, and the distraught driver swerved, the engine stalled, and, once it was going again, they headed across the empty tarmac to the other side of the airfield. Meanwhile Rayle was standing at the open door of the plane, refusing to budge until his “wife” boarded. “My wife went to the ladies room in the terminal and hasn’t come back. We have to wait for her,” he said. The portable stairs were wheeled away, but Rayle planted himself at the open hatch and refused to move. He managed to delay the flight for fifteen minutes. Finally an Italian security officer gestured to him. Svetlana would not be boarding. The stairs were returned and Rayle disembarked, fearing that the Italians had arrested Svetlana.

14

He was taken to a room in the basement of the terminal where about forty security officers were swarming. The colonel in charge was madly shouting into a phone. Eventually Rayle learned that the baggage handler had driven Svetlana to a warehouse on the edge of the airport and abandoned her in an empty hangar.

15

Alone in the dark hangar, Svetlana found a door and walked into what looked like an airport storehouse, where she sat crouched in a stairwell and waited in the eerie silence for almost an hour. Awake since three a.m., she was exhausted and truly frightened. When Rayle found her, though they embraced and laughed, her composure had finally dissolved. The two found refuge in the apartment of a local police officer and waited. The worst news was that her small red suitcase with her manuscript

had been checked onto the plane and was already on its way to Geneva.

16

The frustrated Italians were so anxious to get rid of their unwanted charges that they demanded the Americans charter a plane. A Vickers Viscount airliner was stationed in a far, dark corner of the airfield, ready for the flight to Geneva. Apart from the full crew, Rayle and Svetlana were the only passengers on that 1:00 a.m. flight. This would be her first trip into Europe. Rome didn’t count. She was never

officially

in Rome.

On the plane to Geneva, Rayle kept repeating that he wanted to show Svetlana “Washington, the Lincoln Memorial, everything.” In fact, he said this to reassure her; he had little hope of her getting to Washington soon.

17

He gave her some pertinent advice. She must not admit that she had ever left the international transit lounge in Rome; if the press pestered her with difficult questions, she must simply say, “No comment.” She must not accept the first publisher who wanted her book but instead get the best possible deal. As Rayle wrote to his superiors, “She plans to support herself in the West as a writer so this manuscript right now is all that stands between her and the poorhouse.”

18

On Friday, March 10, the

New York Times

published the first of many stories. Citing unidentified sources, the article was tentative:

Svetlana Stalina, the daughter of Stalin, was reported to have left the Soviet Union for good…. Some reports indicated that she may be in danger. She was said to be seeking visas and may have approached United States officials in New Delhi. It could not be determined why she left the Soviet Union.

19

Svetlana was still a mysterious figure, and there were many errors in the piece. It was claimed that she had married Mikhail

Kaganovich, son of the Politburo member Lazar Kaganovich, in 1951 in a wedding that cost $280,000 and that after Stalin’s death, she had been banished from Moscow. The American Embassy in Delhi and the State Department refused to comment.

But there was soon another dimension to the story. Tony Lucas of the

New York Times

discovered through anonymous sources that Robert Rayle was an undercover CIA officer. Lucas phoned the US Embassy in Delhi and said that if he didn’t receive a disclaimer, he would file the story.

20

The embassy refused to comment. Bob Rayle’s cover as second secretary was blown. Svetlana’s defection in the company of a CIA officer soon became headline news around the world.

When Rayle later submitted a mandatory report to the State Department on the defector’s “personality” and her “adaptability to different environments,” he described Svetlana as “the most completely cooperative defector I have ever met.” He said she’d remained cheerful and optimistic throughout the week as they waited in the safe house, even as she took in the shock that the Americans were refusing her asylum. As Rayle put it, “She recognizes that she cannot be considered a normal, ordinary human being and that her actions have political implications…. You’ll find her a warm, friendly person who responds to warmth and friendliness. I think you’ll find her genuinely likeable.” He added, “She is a very stable person.”

21

But he warned that she seemed quite naive, as if she’d never lived “in any real world,” and would need help in finding her way in the West.

In the early morning hours of March 11, Svetlana “stepped over the invisible boundary between the world of tyranny and the world of freedom.”

22

Of course, it could never be that simple. The strange journey of the second half of her life was about to begin, but if she hoped to escape the shadow of her father’s name, she was tragically mistaken.

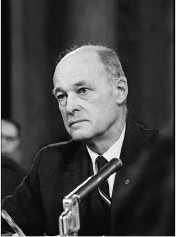

Because he had been the US ambassador to the Soviet Union at the time of Stalin’s death, the diplomat George Kennan, photographed here in 1966, was given responsibility for Svetlana as she began her new life in the United States.

E

arly in the morning on Friday, March 10, the first and second secretaries of the Soviet Embassy in New Delhi

arrived at the Singh estate in Kalakankar. They said Svetlana had disappeared from the Soviet compound and demanded to know where she was. Brajesh Singh’s brother Suresh said that he hadn’t the least idea. Just then the caretaker of the estate rushed in to say the BBC was reporting Svetlana had reached Rome. The face of the first secretary blanched in terror.

“Now we’re through! We’re done for! Oh, my God!”

“So you do believe in God after all, don’t you?” Suresh teased.

“Please, Lal Suresh,” the first secretary said. “This is terrible. I cannot discuss God just now!”

1

This is the story Suresh Singh liked to tell, and it may have been true, but Moscow already knew that Svetlana had left India. Perhaps the secretaries had rushed to Kalakankar hoping against hope that it was all a mistake and she might have returned there. Her defection was on

their

heads. They had shown insufficient vigilance. Had Stalin been alive, they would have been shot.

Behind the scenes, international shuttlecock diplomacy moved at a frenzied pace. In New Delhi, Ambassador Chester Bowles received a letter dated March 9 from Mr. Chandra Shekhar Jha, Indian foreign secretary in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its contents and the ambassador’s response were precisely recorded:

MARCH

9, 1967

The Ministry of External Affairs presents its compliments to the Embassy of the United States of America and has the honour to inform the Embassy that it has come to the knowledge of the Government of India that Madame Svetlana Aluleva [

sic

], a Soviet citizen, who had been on a visit to India and was about to return to the Soviet Union, was given a United States visa and a plane

ticket and was escorted to the United States by an officer of the US Embassy … in full knowledge that she was an important personality.

The Ministry of External Affairs wishes to point out that the above action taken by the US Embassy in such haste without giving any inkling to the Ministry of such impending action, is a source of serious embarrassment to the government of India…. The Government of the Soviet Union have strongly protested to us about what they have characterized as kidnapping of Madame Svetlana Aluleva, a Soviet citizen, by the US Authorities here….

Having regard to all the circumstances of this case … the Government of India strongly urge that Madame Svetlana Aluleva be immediately sent back to Delhi. On her return to India, the Government of India will deal with her in an appropriate manner consistent with international law and practice.

2

Luckily for Svetlana, Ambassador Bowles was mostly on her side. The next day, March 10, he wrote to Jha in a “frank and informal way” responding to what he characterized as Jha’s “secret protest note,” the contents of which were “in no way justified by the facts.”

3

Bowles replied that “Mme. Aluleva [

sic

] had entered the embassy on her own initiative.” No one at the embassy even knew of her existence. She had a valid passport, and her departure had been entirely legal. Numerous employees at the airport could attest to the fact that there had been no coercion. Any attempt by the USSR to suggest otherwise would be “demonstrably false and malicious.”

Bowles assured Jha that, in making his decision, he’d had India’s best interests in mind. If Svetlana had gone to the press as she threatened, India would have been in the middle of a diplomatic nightmare. He’d helped her on her way in accordance “with American tradition stretching back to our earliest years as a nation.”

This was all in the style of diplomatic damage control. However, at the end of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) file containing Bowles’s letter to Jha is attached a disconcerting note, written several days later, containing gossip that the American ambassador in Moscow had collected from a UPI reporter’s poker game.

FROM

MOSCOW, 13 MARCH 1967

Ambassador reports following possibly useful background. Pls pass to appropriate persons in Department. Shapiro comment made in course casual conversation at weekly poker game evening 12 March. Shapiro said he had interviewed children and sent story.

From Ambassador: Shapiro of UPI says Svetlana Stalin reputed to be a nymphomaniac. He says her children convinced mother will return and think possible she mentally upset by death of husband. Shapiro says she was comfortably well off by Soviet standards and that children attractive and appear fond of her.