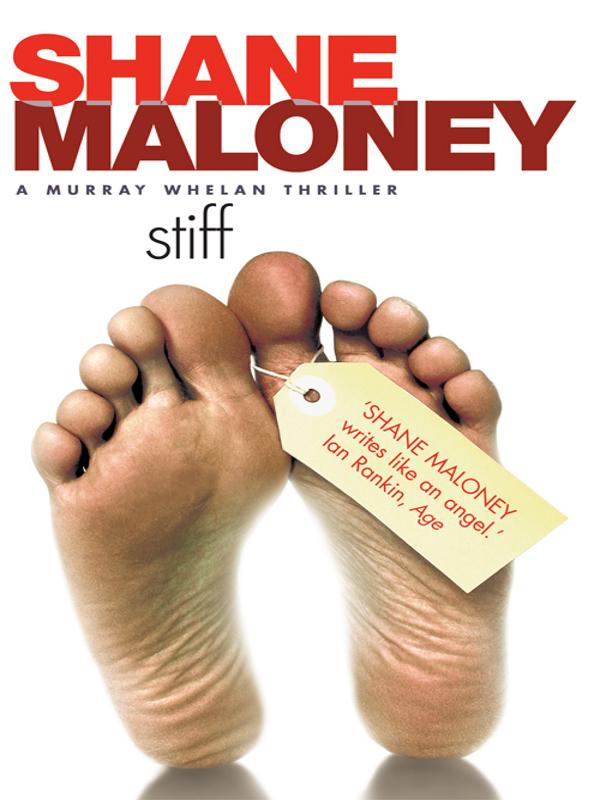

Stiff

Authors: Shane Maloney

PRAISE FOR

STIFF

‘

Stiff

is hilarious…It is a witty, controversial, intelligent book, both genuinely frightening and genuinely funny. A rare combination.’

Herald Sun

‘A fast-paced, fresh, unerringly funny book.’

Houston Chronicle

‘Whelan is a born politico: a breezy, know-it-all wiseacre with a glad hand and a seductively confiding tone of voice.’

Seattle Times

‘Read it, you’ll love it. We want more from Maloney.’

Courier Mail

‘Funny and gripping’

Rolling Stone

‘Maloney pokes fun at almost everything, revelling in words that showcase ludicrous events and behaviour…A rewarding and entertaining read.’

Library Journal

‘Smash debut and finalist for all-round top book of the year:

Stiff

by Shane Maloney…Don’t trust me—this book has been exclusively roadtested by sceptical crime readers and every one of them loved it.’

Melburnian

PRAISE FOR SHANE MALONEY AND MURRAY WHELAN

‘Maloney is top shelf.’

Australian

‘Whelan’s wry social commentaries, ironic observations and many failed attempts at getting the girl make him one of Australian crime-fiction’s most attractive characters, and Maloney one of the genre’s most gifted writers.’

Who Weekly

‘To the list that contains Charles Willeford’s Florida Keys, Jim Thompson’s West Texas, Pete Dexter’s Philadelphia, James Crumley’s Montana and Carl Hiaasen’s Miami, you can add Shane Maloney’s Melbourne. Maloney has created a fictional city that contains the best of the real and the not quite real.’

Herald Sun

‘Maloney is a literary writer who…takes characters that are stereotypes (the public servant, the minister, the arty type) and depicts them with subtlety and originality and compassionate humour. He also writes a ripping yarn.’

Eureka Street

‘Maloney is a born writer…For the first time, in the vicinity of Australian crime-writing, we hear the true national voice of comic futility, a literary voice which is rich, ridiculous and tawdry, which can set itself up with a soaring rhetoric and slide on the banana skin of its own piss-elegance… Maloney is terrific.’

Age

‘A writer who seems to have been sitting on a thousand observations now unleashed.’

Sunday Age

STIFF

Shane Maloney’s novels

include

The Brush-Off,

winner of the Ned Kelly Prize

for Crime Fiction,

Nice Try,

The Big Ask

and

Something Fishy.

SHANE

MALONEY

stiff

A MURRAY WHELAN THRILLER

Shane Maloney is deputy director of the Brunswick

Institute, a weatherboard think-tank financed by his wife.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

www.textpublishing.com.au

Copyright © Shane Maloney 1994

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published 1994, reprinted 1994, 1996, 1998, 2000, 2003

Reprinted 2001 in a compendium edition,

The Murray Whelan Trilogy

This edition published 2004, reprinted 2006, 2007

Printed and bound by Griffin Press

Designed by Chong Weng-ho

Typeset in Baskerville MT by J&M Typesetting

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Maloney, Shane.

Stiff.

ISBN 978 1 921145 13 1.

1. Whelan, Murray (Fictitious character) – Fiction. 2.

Minorities – Victoria – Melbourne – Political activity –

Fiction. 3. Labor unions – Victoria – Melbourne – Fiction.

I. Title.

A823.3

This project was assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its art funding and advisory body.

For Christine

my kind of funding body

The author of this book, its setting

and characters are entirely fictitious.

There is no such place as Melbourne.

The Australian Labor Party exists

only in the imagination of its members.

The fiddle at the Pacific Pastoral meat-packing works was neither particularly original nor fabulously lucrative. But it was a nice little earner for all concerned while it lasted, and probably harmless enough. All that changed when Herb Gardiner reported finding a body in Number 3 chiller.

There it was, jammed between a pallet load of best export boneless beef and half a tonne of spring lamb. It was a Friday afternoon so, if Gardiner hadn’t found it when he did, the corpse would have spent the weekend locked in with the rest of the dead meat, carcasses parked halfway between paddock and dinner plate.

According to the statement Gardiner gave to the Department of Labour investigators and the police, the Number 3 unit had a history of playing up. He had unlocked the door and gone inside to read the gauge when he saw the body squeezed into the aisle running through to the emergency exit hatch. He recognised it immediately as a leading hand with one of the casual work crews, later identified as Ekrem Bayraktar. He didn’t need to feel for Bayraktar’s pulse to know that he was dead. He could tell by the waxy pallor of the man’s face, by the dusting of fine sugar on his lips where his last breath had turned to frost.

The body was sandwiched into a tight space between roof-high stacks of boxes. It was a narrow gap, but it was just wide enough for most men to pass along sideways even in protective clothing—obstruction of access to the emergency hatch was illegal. But Bayraktar was big, even by the standards of a place where men were hired to hump heavy loads around. Later at the morgue his naked corpse weighed in at over 135 kilos, big doughy rolls of flesh, soft obese bulk, like a weight-lifter gone to seed.

He was squeezed in so tight that they had to bring in one of the forklifts to move the loaded pallets around him before they could remove the body. Even without the boxes there to support him he remained upright, balanced like a great big stalagmite. It was hard to imagine how he had got himself that far down the passage, or why.

In the business that followed—the calling of the ambulance, the notification of the police and the Department of Labour, the removal of the body, the taking of photographs and statements—it never occurred to anyone to look for the small zip-lock plastic bag of folded fifties and twenties that Bayraktar had taken into the freezer with him. And even if they had known to look, and where, they would not have found anything. There were quite a few little details about that afternoon that seemed to have been missed.

With Bayraktar gone, everything might have ended then and there and no one would have been any the wiser. It was just bad luck really that his untimely demise coincided with a delicate readjustment then taking place within certain echelons of the Australian Labor Party, an organisation founded to further the aspirations of those who toil unseen in dark and dangerous places. An organisation which, next to itself, loves the working man best.

Perhaps I should begin by saying that this is not a sob story. It’s a cruel world, I know, and even in the just city a man can be stiff. Bad luck happens. And it’s not like bad luck was something I didn’t already know a bit about. Damage control was part of my job, after all. But up until then it had been other people’s bad luck, not my own, that exercised my professional interest. Maybe that’s why I was so unprepared for what happened over those four October days. So I’m not doing any special pleading, you understand. Considering what happened to others I could name, I got off pretty lightly.

It all started on one of those miserable wet Monday mornings when, come nine o’clock, half of Melbourne is still strung out bumper-to-bumper along the South-Eastern Freeway. I had just dropped my son Red at school, and as I swung my clapped-out old Renault into Sydney Road the thought of all those Volvo and Camira drivers stewing away behind their windscreen wipers brought a quiet smile to my lips. Not that I bore them any personal animosity, you understand. It was just that if God wanted to punish the eastern suburbs for voting Liberal, She wouldn’t hear me complaining.

I could afford to feel like that because the Brunton Avenue log-jam was miles away. Where I lived, north of town, the toiling masses tended to start their toiling a little earlier in the day, and most of those that still had jobs were already at work. By nine the rush hour had already come and gone. Apart from a few hundred light industrial vehicles and the occasional tram disgorging early shoppers, women in head-scarfs mainly, I had the northbound lane to myself.

Not that I was busting a gut to get to work. No clock was waiting for me to punch it, and I couldn’t see the pile of paper on my desk bursting into flames if left undisturbed a little longer. The fifteen minutes it took me to drive to work provided one of my few moments of solitude all day and I liked to make the most of it. As I drove, I read the paper.

This was less dangerous than it sounds. I’d already studied the broadsheets over breakfast, and the

Sun

was the kind of tabloid easily absorbed while doing something else—shelling peas, for instance, or operating a lathe. I had it spread open on the passenger seat beside me, and whenever I hit a red light or got stuck behind a slow-moving tram I skimmed a couple of pages. The spring racing carnival had just begun, so the emphasis was on horseflesh, fashion and catering. Just A Dash was favourite, black was big, and interesting things were being done with asparagus. Agreement was unanimous— four years in and the eighties were holding firm as the most exciting decade ever.

The Bell Street lights had changed and I was halfway across the intersection when my eye caught a name buried in a two-paragraph news brief at the bottom of page seventeen. That was when I first encountered the name Ekrem Bayraktar. Not that it meant anything to me at the time. It was the other name that got my attention. I snatched up the page, draped it over the steering wheel and turned my concentration away from the road long enough to constitute a serious threat to public safety. This is what I read.