Stone Fox (2 page)

Authors: John Reynolds Gardiner

SEARCHLIGHT

I

T’S EASY TO

tell when it’s winter in Wyoming. There is snow on everything: the trees, the houses, the roads, the fields, and even the people, if they stay outside long enough.

It’s not a dirty snow. It’s a clean, soft snow that rests like a blanket over the entire state. The air is clear and crisp, and the rivers are all frozen. It’s fun to be outdoors and see the snowflakes float down past the brim of your hat, and hear the squeak of the fresh powder under your boots.

Winter in Wyoming can be the most beautiful time of the year…if you’re ready for it.

Little Willy was ready.

He had chopped enough wood. They would not be cold. He had stocked enough food. They would not go hungry. He had asked Lester at the general store how much food Grandfather had bought last year. Then he had purchased the same amount. This would be more than enough, because Grandfather wasn’t eating very much these days.

The coming of snow, as early as October, also meant the coming of school. But little Willy didn’t mind. He liked school. However, his teacher, Miss Williams, had told Grandfather once, “Far as I’m concerned, that boy of yours just asks too many questions.” Grandfather had just laughed and said, “How’s he gonna learn if he don’t ask?”

Then, later, Grandfather had said to little Willy, “If your teacher don’t know—you ask me. If I don’t know—you ask the library. If the

library don’t know—then you’ve really got yourself a good question!”

Grandfather had taught little Willy a lot. But now little Willy was on his own.

Each morning he would get up and make a fire. Then he would make oatmeal mush for breakfast. He ate it. Searchlight ate it. Grandfather ate it. He would feed Grandfather a spoonful at a time.

After breakfast little Willy would hitch up Searchlight to the sled. It was an old wooden sled that Grandfather had bought from the Indians. It was so light that little Willy could pick it up with one hand. But it was strong and sturdy.

Little Willy rode on the sled standing up and Searchlight would pull him five miles across the snow-covered countryside to the schoolhouse, which was located on the outskirts of town.

Searchlight loved the snow. She would wait patiently outside the schoolhouse all day long.

And little Willy never missed a chance to run out between classes and play with his friend.

After school, they would go into the town of Jackson and run errands. They would pick up supplies at Lester’s General Store, or go to the post office, or go to the bank.

Little Willy had fifty dollars in a savings account at the bank. Every month Grandfather had deposited the money little Willy had earned working on the farm. “Don’t thank me,” Grandfather would say. “You earned it. You’re a good little worker and I’m proud of you.”

Grandfather wanted little Willy to go to college and become educated. All little Willy wanted to do was grow potatoes, but he respected his grandfather enough to do whatever he said.

If there were no errands to run that day, Searchlight would just pull little Willy up and down Main Street. Little Willy loved to look at

all the people, especially the “city slickers,” as Grandfather called them. Why, they didn’t know a potato from a peanut, Grandfather said, and their hands were as pink and soft as a baby’s. You couldn’t miss the city slickers. They were the ones who looked as if they were going to a wedding.

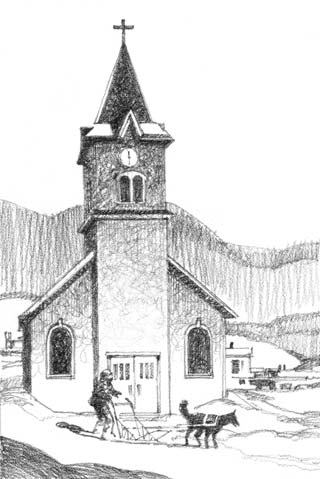

At a little before six each day, little Willy would position his sled in front of the old church on Main Street. Today again he waited, eyes glued on the big church clock that loomed high overhead.

Searchlight waited too—ears perked up, eyes alert, legs slightly bent, ready to spring forward.

B-O-N-G!

At the first stroke of six, Searchlight lunged forward with such force that little Willy was almost thrown from the sled. Straight down Main Street they went, the sled’s runners barely touching the snow. They were one big blur as

they turned right onto North Road. And they were almost out of town before the church clock became silent again.

“Go, Searchlight! Go!” Little Willy’s voice sang out across the snowy twilight. And did Searchlight go! She had run this race a hundred times before, and she knew the whereabouts of every fallen tree and hidden gully. This enabled her to travel at tremendous speed even though it was getting dark and more dangerous.

Little Willy sucked in the cool night air and felt the sting of the wind against his face. It was a race all right. A race against time. A race against themselves. A race they always won.

The small building up ahead was Grandfather’s farmhouse. When Searchlight saw it, she seemed to gather up every ounce of her remaining strength. She forged ahead with such speed that the sled seemed to lift up off the ground and fly.

They were so exhausted when they arrived at

the house that neither of them noticed the horse tied up outside.

Little Willy unhitched Searchlight, and then both of them tumbled over onto their backs in the snow and stared up at the moon. Searchlight had her head and one paw on little Willy’s chest and was licking the underside of his chin. Little Willy had a hold of Searchlight’s ear, and he was grinning.

The owner of the horse stood on the front porch and watched them, tapping his foot impatiently.

THE REASON

“G

ET OVER HERE

!” The voice cut through the air like the twang of a ricocheting bullet.

Little Willy had never heard a voice like that before. Not on this farm. He couldn’t move.

But Searchlight sure could.

The owner of the voice barely had time to step back into the house and close the door.

Searchlight barked and snarled and jumped at the closed door. Then the door opened a crack. The man stood in the opening. He was holding a small derringer and pointing it at Searchlight. His hand was shaking.

“Don’t shoot!” little Willy yelled as he reached

out and touched Searchlight gently on the back. The barking stopped. “Who are you?”

“Name’s Clifford Snyder. State of Wyoming,” the man said with authority. He opened the door a little farther.

The man was dressed as if he was going to a wedding. A city slicker. He was short, with a small head and a thin, droopy mustache that reminded little Willy of the last time he’d drunk a glass of milk in a hurry.

“What do you want?” little Willy asked.

“

Official

business. Can’t the old man inside talk?”

“Not regular talk. We have a code. I can show you.”

As little Willy reached for the door, Clifford Snyder again aimed his gun at Searchlight, who had begun to growl. “Leave that…

thing

outside,” he demanded.

“She’ll be all right if you put your gun away.”

“No!”

“Are you afraid of her?”

“I’m not…afraid.”

“Dogs can always tell when someone’s afraid of them.”

“Just get in this house this minute!” Clifford Snyder yelled, and his face turned red.

Little Willy left Searchlight outside. But Clifford Snyder wouldn’t put his gun away until they were all the way into Grandfather’s bedroom. And then he insisted that little Willy shut the door.

Grandfather’s eyes were wide open and fixed on the ceiling. He looked much older and much more tired than he had this morning.

“You’re no better than other folks,” Clifford Snyder began as he lit up a long, thin cigar and blew smoke toward the ceiling. “And anyway, it’s the law. Plain and simple.”

Little Willy didn’t say anything. He was busy combing Grandfather’s hair, like he did every

day when he got home. When he finished he held up the mirror so Grandfather could see.

“I’m warning you,” Clifford Snyder continued. “If you don’t pay…we have our ways. And it’s all legal. All fair and legal. You’re no better than other folks.”

“Do we owe you some money, Mr. Snyder?” little Willy asked.

“Taxes, son. Taxes on this farm. Your grandfather there hasn’t been paying them.”

Little Willy was confused.

Taxes? Grandfather had always paid every bill. And always on time. And little Willy did the same. So what was this about taxes? Grandfather had never mentioned them before. There must be some mistake.

“Is it true?” little Willy asked Grandfather.

But Grandfather didn’t answer. Apparently he had gotten worse during the day. He didn’t move his hand, or even his fingers.

“Ask him about the letters,” piped up Clifford Snyder.

“What letters?”

“Every year we send a letter—a tax bill—showing how much you owe.”

“I’ve never seen one,” insisted little Willy.

“Probably threw ’em out.”

“Are you sure…” began little Willy. And then he remembered the strongbox.

He removed the boards, then lifted the heavy box up onto the floor. He opened it and removed the papers. The papers he remembered seeing when he had looked for the money to rent the horse.

“Are these the letters?” he asked.

Clifford Snyder snatched the letters from little Willy’s hand and examined them. “Yep, sure are,” he said. “These go back over ten years.” He held up one of the letters. “This here is the last one we sent.”

Little Willy looked at the paper. There were so many figures and columns and numbers that he couldn’t make any sense out of what he was looking at. “How much do we owe you, Mr. Snyder?”

“Says right here. Clear as a bell.” The short man jabbed his short finger at the bottom of the page.

Little Willy’s eyes popped open. “Five hundred dollars! We owe you five hundred dollars?”

Clifford Snyder nodded, rocking forward onto his toes, making himself taller. “And if you don’t pay,” he said, “I figure this here farm is just about worth—”

“You can’t take our farm away!” little Willy screamed, and Searchlight began barking outside.

“Oh, yes, we can,” Clifford Snyder said, smiling, exposing his yellow, tobacco-stained teeth.

THE WAY

T

HE NEXT DAY

little Willy met the situation head on. Or, at least, he wanted to. But he wasn’t sure just what to do.

Where was he going to get five hundred dollars?

Grandfather had always said, “Where there’s a will, there’s a way.” Little Willy had the will. Now all he had to do was find the way.

“Of all the stupid things,” cried Doc Smith. “Not paying his taxes. Let this be a lesson to you, Willy.”

“But the potatoes barely bring in enough money to live on,” explained little Willy. “We went broke last year.”

“Doesn’t matter. Taxes gotta be paid, whether we like it or not. And believe me, I don’t know of anybody who likes it.”

“Then why do we have them in the first place?”

“Because it’s the way the State gets its money.”

“Why don’t they grow potatoes like Grandfather does?”

Doc Smith laughed. “They have more important things to do than grow potatoes,” she explained.

“Like what?”

“Like…taking care of us.”

“Grandfather says we should take care of ourselves.”

“But not all people

can

take care of themselves. Like the sick. Like your grandfather.”

“I can take care of him. He took care of me when my mother died. Now I’m taking care of him.”

“But what if something should happen to you?”

“Oh…” Little Willy thought about this.

They walked over to the sled, where Searchlight was waiting, Doc Smith’s high boots sinking into the soft snow with each step.

Little Willy brushed the snow off Searchlight’s back. Then he asked, “Owing all this money is the reason Grandfather got sick, isn’t it?”

“I believe it is, Willy,” she agreed.

“So if I pay the taxes, Grandfather will get better, won’t he?”

Doc Smith rubbed the wrinkles below her eyes. “You just better do what I told you before, let Mrs. Peacock take care of your grandfather and—”

“But he will, he’ll get better, won’t he?”

“Yes, I’m sure he would. But, child, where are you going to get five hundred dollars?”

“I don’t know. But I will. You’ll see.”

That afternoon little Willy stepped into the bank wearing his blue suit and his blue tie. His

hair was so slicked down that it looked like wet paint. He asked to see Mr. Foster, the president of the bank.

Mr. Foster was a big man with a big cigar stuck right in the center of his big mouth. When he talked, the cigar bobbled up and down, and little Willy wondered why the ash didn’t fall off the end of it.

Little Willy showed Mr. Foster the papers from Grandfather’s strongbox and told him everything Clifford Snyder, the tax man, had said.

“Sell,” Mr. Foster recommended after studying the papers. The cigar bobbled up and down. “Sell the farm and pay the taxes. If you don’t, they can take the farm away from you. They have the right.”

“I’ll be eleven next year. I’ll grow more potatoes than anybody’s ever seen. You’ll see…”

“You need five hundred dollars, Willy. Do you know how much that is? And anyway, there isn’t enough time. Of course, the bank could loan you

the money, but how could you pay it back? Then what about next year? No. I say sell before you end up with nothing.” The cigar ash fell onto the desk.

“I have fifty dollars in my savings account.”

“I’m sorry, Willy,” Mr. Foster said as he wiped the ash off onto the floor.

As little Willy walked out of the bank with his head down, Searchlight greeted him by placing two muddy paws on his chest. Little Willy smiled and grabbed Searchlight around the neck and squeezed her as hard as he could. “We’ll do it, girl. You and me. We’ll find the way.”

The next day little Willy talked to everybody he could think of. He talked with his teacher, Miss Williams. He talked with Lester at the general store. He even talked with Hank, who swept up over at the post office.

They all agreed…sell the farm. That was the only answer.

There was only one person left to talk to. If only he could. “Should we sell?” little Willy asked.

Palm up meant “yes.” Palm down meant “no.” Grandfather’s hand lay motionless on the bed. Searchlight barked. Grandfather’s fingers twitched. But that was all.

Things looked hopeless.

And then little Willy found the way.

He was at Lester’s General Store when it happened. When he saw the poster.

Every February the National Dogsled Races were held in Jackson, Wyoming. People came from all over to enter the race, and some of the finest dog teams in the country were represented. It was an open race—any number of dogs could be entered. Even one. The race covered ten miles of snow-covered countryside, starting and ending on Main Street right in

front of the old church. There was a cash prize for the winner. The amount varied from year to year. This year it just happened to be five hundred dollars.

“Sure,” Lester said as he pried the nail loose and handed little Willy the poster. “I’ll pick up another at the mayor’s office.” Lester was skinny but strong, wore a white apron, and talked with saliva on his lips. “Gonna be a good one this year. They say that mountain man, the Indian

called Stone Fox, might come. Never lost a race. No wonder, with five Samoyeds.”

But little Willy wasn’t listening as he ran out of the store, clutching the poster in his hand. “Thank you, Lester. Thank you!”

Grandfather’s eyes were fixed on the ceiling. Little Willy had to stand on his toes in order to position the poster directly in front of Grandfather’s face.

“I’ll win!” little Willy said. “You’ll see. They’ll never take this farm away.”

Searchlight barked and put one paw up on the bed. Grandfather closed his eyes, squeezing out a tear that rolled down and filled up his ear. Little Willy gave Grandfather a big hug, and Searchlight barked again.