Stories for Boys: A Memoir (19 page)

Read Stories for Boys: A Memoir Online

Authors: Gregory Martin

Beside the door, he stepped into his boat shoes. He took his jacket from its hook. He turned the deadbolt, let himself out the side door, and walked down the rickety wooden steps to the red Ford Escort in the open carport. He turned the key in the ignition and the engine coughed and turned over. He opened the glove compartment and reached his arm behind the back panel and pulled out his cigarettes. He shook one out and put it to his lips. He wouldn’t light it until he got there, until he was outside the car, waiting. He backed out of the driveway and drove off.

Self-Promotion

WALT WHITMAN IS NOT KNOWN FOR RESTRAINT OR SELF-CENSORSHIP. The man wrote and published not one but several glowing, anonymous reviews of his own book.

An American Bard at last! One of the roughs, large, proud, affectionate, eating, drinking, and breeding, his costume manly and free, his face sunburnt and bearded, his posture strong and erect, his voice bringing hope and prophecy to the generous races of young and old. We shall cease shamming and be what we really are…No sniveler, or tea-drinking poet, no puny clawback or prude, is Walt Whitman… The body, he teaches, is beautiful. Sex is also beautiful. Are you to be put down, he seems to ask, to that shallow level of literature and conversation that stops a man’s recognizing the delicious pleasure of his sex, or a woman hers?

In the third edition of

Leaves of Grass

, Walt Whitman added an untitled poem believed to be an account of the aftermath of Whitman’s love affair with a younger Irishman named George Vaughan. But Whitman cut this poem from the fourth edition and all subsequent editions of

Leaves of Grass

. It’s nowhere to be found in my Modern Library copy (the “deathbed” edition). In the poem, Whitman is not his affirming, universal, celebratory self. He is abandoned and bereft.

Leaves of Grass

, Walt Whitman added an untitled poem believed to be an account of the aftermath of Whitman’s love affair with a younger Irishman named George Vaughan. But Whitman cut this poem from the fourth edition and all subsequent editions of

Leaves of Grass

. It’s nowhere to be found in my Modern Library copy (the “deathbed” edition). In the poem, Whitman is not his affirming, universal, celebratory self. He is abandoned and bereft.

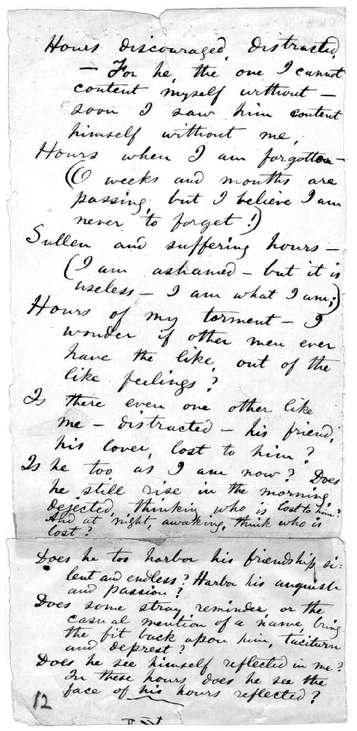

Sullen and suffering hours – (I am ashamed – but it is useless – I am what I am;)Hours of my torment – I wonder if other men ever have the like out of the like feelings?Is there even one other like me – distracted – his friend, his lover, lost to him?Is he too as I am now? Does he still rise in the morning, dejected, thinking who is lost to him? And at night, awaking, think who is lost?Does he too harbor his friendship silent and endless? Harbor his anguish and passion?Does some stray reminder, or the casual mention of a name, bring the fit back upon him, taciturn and deprest?Does he see himself reflected in me? In these hours does he see the face of his hours reflected?

My father is one other like Whitman – rising in the morning, dejected, thinking who is lost to him. And at night, awaking, thinking who is lost. My father harbors his friendship silent and endless. He harbors his anguish. Stray reminders, or the casual mention of a name, brings the fit back upon him, taciturn and depressed. Unlike Whitman, my father has never – to my knowledge – felt this way about another man. My father feels this way – he will always feel this way – about my mother.

THIS POEM THAT Whitman cut from the fourth edition of

Leaves of Grass

was one of twelve poems that appear in Whitman’s notebooks, known to scholars as the “Live Oak, with Moss” sequence. In these poems, Whitman is unambiguously homosexual. Whitman had written of “manly love” before, but abstractly, celebrating human sexuality in all its forms – what one scholar called Whitman’s “cosmo-eroticism.” Nowhere else in Whitman’s poetry is there such a sustained account of homosexual love. Nowhere else in more than half a century of publishing poems is Whitman so personal or direct. Scholars speculate that, had Whitman published these twelve poems intact, they would have been the first homosexual coming out account in American literature.

Leaves of Grass

was one of twelve poems that appear in Whitman’s notebooks, known to scholars as the “Live Oak, with Moss” sequence. In these poems, Whitman is unambiguously homosexual. Whitman had written of “manly love” before, but abstractly, celebrating human sexuality in all its forms – what one scholar called Whitman’s “cosmo-eroticism.” Nowhere else in Whitman’s poetry is there such a sustained account of homosexual love. Nowhere else in more than half a century of publishing poems is Whitman so personal or direct. Scholars speculate that, had Whitman published these twelve poems intact, they would have been the first homosexual coming out account in American literature.

But Whitman broke up the sequence, distributing them out of their chronology among the forty-five poems of the newly added “Calumus” section of the third edition (1860) of Leaves of Grass before cutting the most personal of the poems from the fourth edition (1867).

Whitman didn’t just cut the poems from Leaves of Grass; he cut them from his notebooks. He took scissors and literally cut them out. One hundred years later a scholar put them back together again – humpty-dumpty style – following the order of the numbers Whitman used to title the sequence. If you look at the archive photographs of the poems you can see the joints where they’ve been taped back together. One hundred years later this handwritten poem sequence was made whole again.

What Walt Whitman cut from Leaves of Grass was his shame. His shame is even contained by parentheses,

(I am ashamed –but it is useless – I am what I am;)

as if to acknowledge it at all is barely speakable – as if he is ashamed of his shame. Perhaps not. Perhaps he wanted nothing in his work to undermine his life-long affirmation of human sexuality in all its complexity. Or perhaps he found the poems self-pitying. I don’t. I find Whitman more human, more universal without the grand first person plural, more sympathetic, because he is in so much doubt and despair, because he is, as always, seeking connection.

IN AN EMAIL he sent me less than three months after his suicide attempt, my father wrote:

I have thought many times in my life that if I could start over again, I would find a way to not be the way I am. Unfortunately, there is no way to turn the clock back and do it over. I am who I am and must find a way to live with this self and this way of life.

Acclimation

CHRISTINE, THE BOYS, AND I WENT OUT TO DINNER WITH my father on one of his visits. We went to Bumblebees, a chain Mexican restaurant within walking distance of our house, in a hip-for-Albuquerque neighborhood called Nob Hill. We sat down at a table next to six men. Three couples. They were all approximately my age, in their late thirties or early forties. They were talking and laughing. My father did not stare. He ate his burrito. He patiently listened to plot summaries of the morning’s cartoons. He ranked his favorite superheroes and provided convincing justifications. He gave no sign that he was interested in the conver - sation at the table next to us. Three years earlier, I would have thought nothing of this. I would not have been in awe of his ability to appear as if there was nothing he longed for in that restaurant that he did not have.

When we were done with dinner, my father held the door, and we all walked out of the restaurant. When he let the door go, I looked my father in the eye. “You heard every word they said.”

He nodded. “They were just talking about their lives.”

I put my hand on his shoulder, and we stood there for a moment as Christine and the boys walked down the sidewalk. The cars on Central rushed by. My father and I started to follow. My father said, “I can’t get used to it.”

Affective Forecasting

WHEN MY MOTHER INSPECTS HER MEMORY, SHE REMEMBERS many times when she should have wondered out loud, to my father: Where were you? Why were you out so late? WHAT were you doing? Really? Are you lying to me? How do I know that what you’re telling me is true? What is going on? My mother knew risk theory. She knew that loss aversion induced a strong bias toward the status quo. She just wasn’t aware that she was failing to apply this fundamental principle to her marriage. Or to say that another way: in hindsight, she can see how many times she looked the other way.

When my mother divorced my father – when she chose to never see him again – she did not base this decision on social science. But it turns out that this was the best thing she could have done for both of them, according to research in the relatively new field of affective forecasting – the study of how we predict we will feel in the future. In one study, conducted by the psychologist Daniel Gilbert, undergraduates chose two favorite photographs from photographs they had taken all over campus, and they developed and blew these two photos up in a darkroom into black and white eight-by-ten glossies. Then they were told to pick one and give Gilbert the other. They couldn’t have both.

… Now there are two conditions in this experiment. In one case, the students are told, ‘But you know, if you want to change your mind, I’ll always have the other one here …’The other half of the students are told exactly the opposite. ‘Make your choice.’… right before the swap and five days later, people who are stuck with that picture, who have no choice, who can never change their mind, like it a lot! And people who are deliberating, ‘Should I return it? Have I gotten the right one? Maybe this isn’t the good one? Maybe I left the good one?’ – have killed themselves. They don’t like their picture.

Gilbert doesn’t mean the students really killed themselves. That’s a figure of speech. Here’s what he means. “The psychological immune system works best when we are totally stuck. When we are trapped …”

When there is no longer any possibility of a shared future. When there is nothing left but memories.

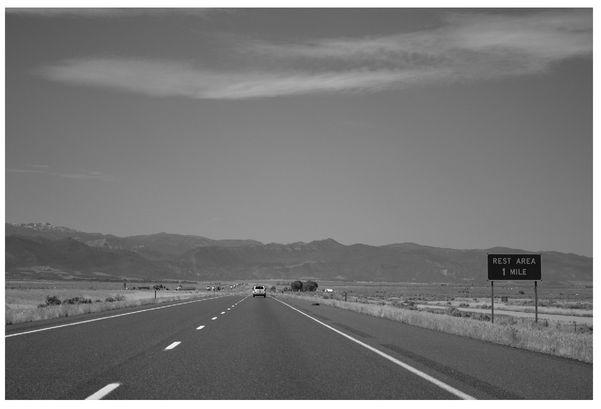

Rest Area

WE’RE DRIVING I-80, FROM our home in Lincoln, Nebraska, to northern Nevada, to visit my grandparents – my mother’s parents. I am six or seven years old. Western Nebraska, northern Colorado, Utah. We stop at a rest stop. I enter the dim concrete, bunker-like men’s room with my brother and my father. We all pee next to each other, the three of us in a row. I’m just tall enough to use the urinal. I don’t have to go inside the stall anymore to pee.

We come back out of the building. I’m wearing my Sinclair hat, with its signature green brontosaurus logo, which my parents bought me earlier that day. The visor of my Sinclair hat helps block the bright Utah sun.

My father turns and takes a knee, so he can look my brother and me in the eyes. He says, “I don’t want you to ever go into a rest area bathroom without an adult. Do you understand?” His tone is not at all harsh, but he’s serious.

Why?

“I’ll tell you. Bad people can be in rest area bathrooms. A man pulled a knife on me one time in a rest area bathroom. I thought he was going to kill me.”

Why did he do that?

“He wanted my billfold.”

Did you give it to him?

“I did.”

Other books

A Lady Never Trifles with Thieves by Suzann Ledbetter

The Ghost in the Third Row by Bruce Coville

The Morgue and Me by John C. Ford

H. M. S. Cockerel by Dewey Lambdin

Wide Open by Tracey Ward

Gale Force by Rachel Caine

The Duchess Diaries: The Bridal Pleasures Series by Jillian Hunter

Darkness Betrayed (Torn) by Hughes, Christine

The Wages of Sin [The Mysterious] by Alex Beecroft