Stories for Boys: A Memoir (7 page)

Read Stories for Boys: A Memoir Online

Authors: Gregory Martin

Evan does not need to be protected from me. I did not need to be protected from my father. On the first day of preschool, at the end of the summer of 2007, as Evan was standing and peeing and flushing, as he was washing and drying his hands, I stood in the doorframe and all I wanted to do was scream.

IN

SONG OF MYSELF

, Walt Whitman wrote:

SONG OF MYSELF

, Walt Whitman wrote:

Unscrew the locks from the doors!

Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!Whoever degrades another degrades me;

And whatever is done or said returns at last to me.

The Family Plot

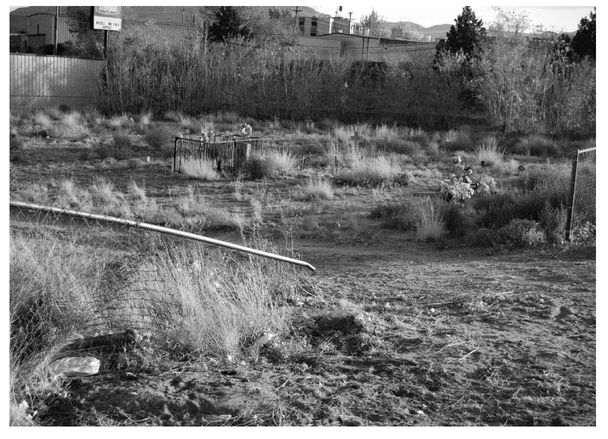

ONE SUNDAY MORNING, I FOUND MYSELF WANDERING through a graveyard near our house, up and down the rows of faded pink cloth roses and sunken headstones. I didn’t know a soul buried there, and I didn’t know what connection or solace I expected to find. All I knew was that, here, if anywhere, was an object lesson on impermanence: hundreds of graves bordered by a six-lane thruway, a storage warehouse, and two used-car lots packed with balloons and SUVs. There was no entrance, just an opening where the drooping chain-link fence fell apart completely. It looked like an urban vacant lot littered with plastic bags, Styrofoam cups, rusted pipes, and crosses.

For five years, I’d been driving past at forty miles an hour on the way to the boys’ preschool, first with Oliver and then with Evan. The graveyard nagged at my conscience. I didn’t know why no one picked the place up. I didn’t know if this bothered anyone but me. This was the closest cemetery to my home in a quiet neighborhood, less than a mile from the university where I was a teacher, but I didn’t know its name.

The first grave beyond the opening in the chain-link fence was the most recent. There was no headstone. A body-sized, dirt mound rose a foot above the earth, surrounded by fist-sized rocks, like a pioneer’s grave on the wagon train west, or a potter’s field grave, dug quickly and late at night. On a small, green metal stand, in a frame under glass, these words were printed on weathered paper:

There was an address and a phone number for the funeral director. I dialed the number on my cellphone. It rang twice and a man named Ed Hatton answered. He seemed unsurprised by my call and the fact that I was standing at Esteban Salido’s grave. He was having Sunday brunch at a restaurant with his family, but he had a few minutes. He seemed like a man accustomed to phone calls involving death and odd circumstances.

He remembered Esteban Salido. I asked him if he knew the name of the graveyard I was standing in. He didn’t. But he said there were other graveyards like it, family graveyards, spread out over the Rio Grande Valley. He named one just off the interstate by the airport and another near the Balloon Fiesta Park. He interrupted himself to order the ranch omelet and then told me about the Albuquerque Indian School graveyard, where Pueblo and Navajo children were buried between 1882 and 1933. There were no signs now at all of their graves; it was a 4-H park and a playground. He said I wouldn’t believe how many graves get dug up each year by construction workers. Our connection went bad for a few seconds but then he was saying how sad it made him that people were losing the sacred places of their family’s past. I could hear, in the background, the clinking of plates and forks, but Ed Hatton was unhurried, eloquent, and I stood there in front of Esteban Salido’s grave, under a hot August sun, and listened. Ed ran a mortuary now, but he had once managed a number of family cemeteries. So many people now lived far away from where their loved ones were buried. They had nowhere to go to mourn. “You have called about something very close to my heart,” he said. I thanked him for taking time away from his family and his breakfast, and he said, “No, thank

you

.”

you

.”

I LEFT BEHIND Estaban Salido’s grave and walked among the haphazard rows of graves, headstones weathered, cracked, the letters faded or nearly illegible. Some were ringed by rocks, railroad ties, rotted two-by-fours, or bricks. Wooden crosses, rebar crosses. Discarded pipes and plumbing, a rain-soaked mattress, faded pink flip-flops, a sun-bleached teddy bear.

All that summer I’d felt out of place in the most literal sense. Not one of the familiar places in my life – my home, my neighborhood, my office, the playground, the swimming pool – gave me any solace. Not one of those places could contain my sorrow for my father and mother or my own feelings of confusion. But as I walked among the abandoned dead that August morning, my heart felt strangely light. I was happier than I had been in months. I was so surprised by the dissonance between the neglect before me and the way I was feeling that I laughed out loud.

A graveyard is a wilderness, a place beyond boundaries, a home for unknowns and loss.

MY FATHER DID not attend his father’s funeral. I don’t know the name or location of the graveyard where my father’s father is buried. I don’t know the year he died or how old he was or what condition or event killed him. I never met him. I have never seen his picture. I don’t know if my father resembles him, or if I resemble him, or if my sons resemble him. My father rarely spoke of him, except to say that he was a violent drunk who beat his mom and sisters – he never once beat my father.

I don’t want to know where my father’s father is buried. I don’t want to go there with my shovel and my rage and unearth his skeleton and tear it apart, bone by bone, then smash each bone to pieces and take what remains far away to a place where no one ever knew or loved him and scatter it all in a vacant lot.

ON AUGUST 16TH, the same day Christine and I celebrated our tenth wedding anniversary, my parents signed the papers making official their divorce. The next day, my mother’s Last Will and Testament arrived in the mail.

I, DOLORES (DEE) TREMEWAN MARTIN, a single woman, of Spokane, Washington, being of sound and disposing mind and memory, and not acting under any duress, menace, fraud or the undue influence of any persons, make my Last Will and Testament, revoking all previous wills and codicils.

On page three, my mother states that her remains shall be cremated and her ashes buried in Elko, Nevada, in the center of the Tremewan Family Plot.

My headstone will read: Dolores Tremewan Martin, June 11, 1940 – “date of death”.

My mother will be buried in the town where she was born, beside her mother and father and sisters, beside her aunts and uncles and cousins, beside the friends of her childhood, and the childhood friends of her parents. My mother has not lived in Elko for more than fifty years.

In the six-page document, there is not a single mention of my father.

My father will be cremated. He has told me that he does not care what happens to his ashes.

MY FATHER’S SUICIDE attempt was an exhumation. The person he could not speak of had been unearthed. My father was more alive, and more alone, than ever.

Epiphany

MY FATHER’S SECRET LIFE WAS UNDONE BY TECHNOLOGICAL, not social, progress – an innovation known as “tabbed browsing.” He’d recently downloaded the new Microsoft Internet Explorer 7 on the home computer and was just getting the hang of it. The window he left open was unincriminating, a news website; the tabbed window behind this was not. The pornographic images of men my mother discovered on the screen left nothing to the imagination.

My father put it this way in an email:

A small change in the web page structure caught me in an unguarded moment and changed the lives of the entire family.

The word “epiphany” comes from an ancient Greek word meaning “manifestation” or “striking appearance.” James Joyce took this concept and adapted it to his theory of storytelling. In a letter to his brother Stanislaus, Joyce explained that epiphanies were “inadvertent revelations … by which people betrayed the very things they were most careful to conceal.”

The Feast of the Epiphany, in the Catholic liturgical calendar, falls on the 6th of January, but my mother entered the upstairs office and was confronted with an inadvertent revelation that led to an epiphany on March 17th, St. Patrick’s Day. It can’t help that her memories of the men on that computer screen have become associated with leprechauns.

Much later, my mother told me, “We went to a wedding that night. Neither one of us said a word. When we came home, I said, ‘What is going on?’ I hadn’t put it together. I can see now that I was in complete denial. We hadn’t had sex in more than ten years. When I tried to talk about this with him, he would get angry, come up with all kinds of excuses – like that his back hurt.” My mother interrupted herself to laugh out loud. “He refused to see a marriage counselor. He stayed up for hours after I had gone to bed. But I just couldn’t see the big picture. I thought it shouldn’t matter. We were happy. I didn’t want to see the big picture.

“Your father said, ‘Do you want me to leave?’ I told him I wanted him to tell me the truth. I shouted this at him. I was mad as hell. I still didn’t get it. I was thinking, he better give me some explanation. I still thought there must be some explanation, and that this explanation would make things right. That’s when he told me that his father had molested him when he was a boy. That he’d been molested for years. But he didn’t cry when he told me this. I didn’t cry, either. I was too confused, too much in shock.”

My mother and father remained living together in a cold, awful silence for six more weeks. My father denied that he was gay. He met her questions with silence. He stared at her until she walked away. Or he walked away. In the mornings, they went to work. In the evenings, they came home, ate dinner and slept in the same bed. They had increasingly escalated arguments. My mother went to see a counselor, who said, “I think your husband is gay.” The counselor told my mother to confront him. Ask him. My mother said she already had. The counselor told her to confront him again.

My mother confronted my father again, “Are you gay?”

“No,” he said.

My father refused to see this counselor with my mother. My mother told him to pack his bags. My father agreed to see this counselor with my mother.

The counselor asked my father, “Are you gay?”

My father said, “Yes, and I have been all my life.”

THESE LONG, AWFUL, six weeks included the non-celebration of their 39th anniversary, on April 1st, which every year is April Fool’s Day – a day that had always involved happiness, gratitude, and some kind of playful practical joke, a day that had never before been laced with such poisonous irony. At least not for my mother.

Can We Make Patients Better Off by Prolonging Their Pain?

1

1

FOR BOTH MY MOTHER AND FATHER, THE MEMORY OF those six weeks, that time when the life they shared together unraveled, was made measurably worse by my father’s suicide attempt, according to the research of the psychologist and Nobel Laureate, Daniel Kahneman.

Kahneman discovered, among other things, that the character of our memory is determined largely by the peak intensity experienced during an episode, and by the intensity of when the episode ends. He found, as you would guess, that less painful endings generated better memories than severely painful endings.

2

But Kahneman also found something deeply counterintuitive:

2

But Kahneman also found something deeply counterintuitive:

…an episode of 60 seconds during which one hand is immersed in painfully cold water will leave a more aversive memory than a longer episode, in which the same 60 seconds are followed by another 30 seconds during which the temperature rises slightly. Although the extra 30 seconds are painful, they provide an improved end. When experimental participants are exposed to the two episodes, then given a choice of which to repeat, most choose the longer one.

Other books

Death Bringer (Soul Justice) by Pearce, Kate

Hallowed by Bryant Delafosse

Wumbers by Amy Krouse Rosenthal

Across a Thousand Miles by Nadia Nichols

Breakthrough by J.H. Knight

Paradise Hops by Crowe, Liz

Long Black Curl by Alex Bledsoe

Gypsy by J. Robert Janes

In The Shadows of the Cavern of Death (Shadows of Death Book 1) by Angelique Jones

Broken Ground by Karen Halvorsen Schreck