Stories for Boys: A Memoir (6 page)

Read Stories for Boys: A Memoir Online

Authors: Gregory Martin

Should we tell them that Grandpa was gay? Maybe we could tell them that Grandpa was gay for a very long time but he didn’t know how to tell Granny the truth. Maybe that was what we should do. Start there. We’d told Oliver and Evan that for so long in America people who were gay were not just treated cruelly but sometimes even murdered, and that this sometimes even happened now. Yes. For a long time people even thought that if you were gay or lesbian that you were crazy. Some people still believed this. Some people even believed that God thought it was a sin to be gay. Hard to believe, but true.

BUT THERE WAS no way we were going to tell the boys anything about suicide. And no way we would tell them something terrible had happened to Grandpa a long time ago, when he was a little boy. Someone had touched his private parts in an awful way that had hurt him very much. No. This someone was his own father. No.

The boys understood that no one was to ever touch their private parts. Oliver was the only one who touched Oliver ’s private parts. Evan was the only one who touched Evan’s private parts. If Oliver or Evan wanted to touch their own private parts, that was just fine, but they should do this privately, like in their own bed, and not out in the open on the living room floor where they were also playing with Legos. Christine had an amazing ability to say exactly this to the boys, especially when they were four and five, in the most kind, offhand way. “Hey,

name of Cooney-Martin boy

, sweetheart, it’s just fine if you want to touch your penis, but you should touch your penis in your bunkbed and not out in the living room. You can come back and play with your Legos when you’re done.” Sometimes

name of Cooney-Mar - tin boy

simply stopped touching his penis and turned more of his attention to his Legos with a kind of casual “Sure, Mom,” unspoken recognition. Sometimes

name of Cooney-Martin boy

would stop playing Legos and take his mom up on her suggestion and go to his bunkbed for a while and then come back. At such times, I felt toward Christine the way young, untrained Luke Skywalker feels toward Yoda when he levitates Luke’s drowned x-wing fighter out of the Dagobah swamp.

How did you do that?

I watched Christine employ this Jedi suggestion more than a few times before I felt confident enough to attempt it myself. Then I did, and it worked. May the force be with you.

name of Cooney-Martin boy

, sweetheart, it’s just fine if you want to touch your penis, but you should touch your penis in your bunkbed and not out in the living room. You can come back and play with your Legos when you’re done.” Sometimes

name of Cooney-Mar - tin boy

simply stopped touching his penis and turned more of his attention to his Legos with a kind of casual “Sure, Mom,” unspoken recognition. Sometimes

name of Cooney-Martin boy

would stop playing Legos and take his mom up on her suggestion and go to his bunkbed for a while and then come back. At such times, I felt toward Christine the way young, untrained Luke Skywalker feels toward Yoda when he levitates Luke’s drowned x-wing fighter out of the Dagobah swamp.

How did you do that?

I watched Christine employ this Jedi suggestion more than a few times before I felt confident enough to attempt it myself. Then I did, and it worked. May the force be with you.

In that first week after my father attempted suicide, Christine asked the boys if Grandpa had ever touched them inappropriately, and they’d said no and gone back to playing with their matchbox cars. I was still in Spokane when this happened, but I knew what their answer would be. My father had never been in anyway sexually inappropriate with me. I told Christine this, but I knew she needed to ask anyway. I wanted her to ask. I’d asked my father the same thing.

The day after he came out of his coma, I arrived at the hospital early in the morning, took the elevator up to the fifth floor, to the psychiatric ICU. I sat beside my father. He was not asleep. He was staring blankly at the wall. My mother had already been there, but had gone somewhere, and he was alone in the room. I said, “I need to ask you something.”

He looked at me.

“Did you ever, in anyway, abuse Oliver or Evan?”

My father did not seem surprised that I asked him this question. He stared at me coldly.

I said, “Some people who are abused end up abusing others. That’s how it happens.”

My father stared at me some more. Finally he said, “Your mother asked me the same thing. She asked if I ever abused you or your brother. Then she asked if I ever abused your boys.” An awful look came into his face, a rageful look I didn’t think he was capable of. “I would never hurt a child. I have never abused anyone. Never.”

I nodded my head. “I know,” I said. “I just needed to hear you say so.”

THOSE FIRST MONTHS after my father’s suicide, Christine and I talked about what we should tell the boys. I kept bringing it up. I could not help myself. I asked her at night before we went to sleep and in the morning before the kids woke up. I said, “Don’t you think we should tell them?” I asked her when we were driving the kids to the swimming pool or to the zoo, so that Oliver or Evan would shout out, “Tell them what? What should you tell us?” Sometimes I said, “When do you think we should tell them?” Because that was a question about timing, and not about whether we would tell them or not. I drank my second cup of coffee and waited for Christine to wake up, and I said, “I think we should tell them today.”

Christine didn’t think we needed to tell them anything. Not now. They were too little. We would wait until they were older, until they were old enough to understand. And even then, we wouldn’t tell them everything. We would tell them that Grandpa was gay, but we might never tell them about incest or suicide. For her, there was no real dilemma.

Besides bringing it up too much, I didn’t really argue, but I couldn’t come close to Christine’s certainty, her conviction. In those first months after my father’s suicide attempt, my mind didn’t work well. It was all a sad, confusing, inarticulate muddle. In my memory, our conversations ended in paralysis and indecision. But Christine remembers differently. She remembers a fierce clarity, an instinctive determination to protect the boys from psychological harm. She remembers not indecision, but anger at the very fact that our little boys were in danger of ever discovering this knowledge, this truth.

I nodded, I agreed, I said okay. But telling the boys nothing did not sit well with me. The idea that there were things about our family we might never tell the boys burned inside me. And I didn’t know why. No, it’s more true to say that I didn’t think to ask myself why. I just wanted to tell them. I didn’t want there to be any secrets between us. I wanted to just start telling them, and see where that lead us. I wanted to tell them more than I wanted to protect them from what I might tell them. I wanted to tell them more than I wanted them to understand. Understanding would come later. A part of me knew this was irrational, though I never articulated it to myself, much less to Christine. So after a while, I stuffed this impulse when it came to me, which was often, sometimes several times a day.

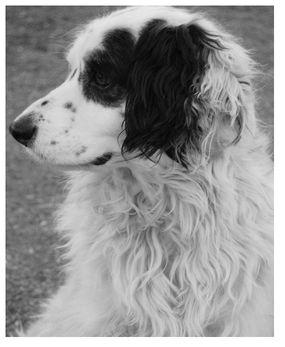

Rocky

I WOKE UP EACH MORNING AT FOUR-THIRTY OR FIVE. I couldn’t sleep. I peed. I let Rocky out to pee. I made coffee. I let Rocky back in. I fed him. I was exhausted. I didn’t turn the lights on. I sat down at the kitchen table and looked out the window. Mostly I saw my own reflection. My sadness was like a low-grade fever that wouldn’t come down. I did not want to “sit” with my feelings, but there I was. I liked to think of myself as “a man of action.” Christine sometimes called me “Mr. Incredible” after the chubby, forced-into-early-retirement dad/superhero of the Pixar movie,

The Incredibles

. But there was no villain to defeat, no one to rescue. I could not keep my father from sitting alone at his card table in his cheap apartment. I could not keep him from his shame. I could not keep my mother from reconfiguring her memories, from replaying the tape of thirty-nine years of marriage and doubting even the smallest of moments. I could not return her trust to her. I could not explain to my children why their grandparents had divorced and why I was so sad. There was nothing to do. So I sat there and waited for the day to start. Dawn came slowly. Coffee helped some. Rocky sat at my feet at the kitchen table.

The Incredibles

. But there was no villain to defeat, no one to rescue. I could not keep my father from sitting alone at his card table in his cheap apartment. I could not keep him from his shame. I could not keep my mother from reconfiguring her memories, from replaying the tape of thirty-nine years of marriage and doubting even the smallest of moments. I could not return her trust to her. I could not explain to my children why their grandparents had divorced and why I was so sad. There was nothing to do. So I sat there and waited for the day to start. Dawn came slowly. Coffee helped some. Rocky sat at my feet at the kitchen table.

Rocky and I had been spending a lot more time together lately. He had uncanny emotional radar. If someone was sad or having a hard time, Rocky jumped up on the couch beside them, put his head in their lap, and gave them the opportunity to feel better by petting him. If Christine and I had any kind of disagreement, however mild, the winner was the one Rocky stood beside. It did not matter if you were right. It mattered how sad you were. I did not win often. But that was changing. Rocky liked me better broken. He didn’t need to know why. He’d always treated me with the wary affection of the beta male, ever ready to roll over and bare his throat and belly. Now he rested his chin on my slippers, so that I couldn’t move my feet. I felt powerfully sorry for myself. I had been cured of my optimism bias and become more like a citizen of Denmark. The Danes, according to

The New York Times

, “are perennial pessimists, always reporting low expectations for the year to come. They then find themselves pleasantly surprised when things turn out rather better than expected.”

The New York Times

, “are perennial pessimists, always reporting low expectations for the year to come. They then find themselves pleasantly surprised when things turn out rather better than expected.”

Subject: What’s going on in my lifeDate Fri, 20 July 2007I really am sorry I was so inconsiderate for not responding to your email, the book and the CD. I am really appreciative of the Kingston Trio CD. I have it in my CD player in the car (as I don’t have one in the apartment) and listen to it anytime I go anywhere. Those are two great albums and bring back many fond memories of my early days as a Folk aficionado. I find myself singing/humming one or another of the tunes frequently at work. I’m glad Oliver is enjoying the water squirter. I picked one with two squirt guns so he could share with Evan and have someone to play with, especially when no other kids were around.As to what else is going on in my life, it is basically the same as it was before, with the exception that I am unable to share it with Dee, and to share in her daily life. Of course I miss her enormously and will probably do so for the rest of my life. Your Mother was my life. I didn’t have friends outside her circle of friends and acquaintances. There is now a gargantuan hole where a normal existence used to be. Don’t tell me this isn’t penance or consequence. When anyone asks, “How are you?” the response is, “Well, OK” or “As well as can be expected, I guess.” I can’t even begin to describe the depth of that hole. Now, given that, please don’t think that your Mother’s grief is not wider and deeper. I am aware that all these years, I knew what I was doing and she didn’t. I am also aware of how deeply she loved me and how utterly devastated she must be. As bad as I feel, her pain is worse than mine. I wish there was something I could do to alleviate that pain. I will try to find some way if I can.Thanks for bringing me to task. I clearly needed it. I love you and please give my love to Christine, Oliver, and Evan – even Rocky.Dad

Stand and Deliver

THE POET WILLIAM STAFFORD WROTE OF THE “REMOTE important region in all who talk.” In 1945, when my father was four years old, that remote, important region inside him was desecrated.

Evan was four years old the summer after my father attempted suicide, and he was an accomplished talker. He talked about past and future playdates, the plots of his favorite cartoons, the girls he and Oliver chased on the playground at the park. He was capable of monologues of ten minutes or more. But there were many moments when I couldn’t listen because images of Evan combined with what I imagined had happened to my father into an awful mixture of revulsion and rage and helplessness, and Evan would see that I was not really there, and he’d say, “Daddy, what’s the matter?”

ON THE FIRST day of preschool, Evan marched into the bathroom like a kid with something to prove. A few weeks earlier, he’d decided it was time to stand and pee. His aim was unreliable, but that wasn’t the point. He was a big boy. He was thirty-seven inches tall, his belly convexly toddlerish, not flat like his seven-year-old brother. He weighed thirty-five pounds. He could pull up his underpants and then his shorts, all by himself, to his great pride and mine. Related complex tasks, once beyond him, had become routine. Standing on the stool in front of the sink, he could:

1. turn on the faucet and wet his hands

2. push down a fat dollop of soap from the dispenser

3. vigorously rub his hands together

4. rinse

5. turn off the faucet, and

6. dry his hands with a towel instead of his shirt.

The preschool bathroom has no door. What is beautiful about this is that Evan and his pre-schoolmates don’t care. What is beautiful is their innocence, their trust, their absence of self-consciousness, their absence of shame. They do not need a door. What is abhorrent and ugly is that, because of the corrosion of some people’s hearts, there must be no door.

Other books

Howl (Howl #1) by Morse, Jody, Morse, Jayme

Gutted by Tony Black

Putting Out the Stars by Roisin Meaney

The Great Destroyer by Jack Thorlin

Walking on Air by Janann Sherman

Homewrecker (Into the Flames #1) by Cat Mason, Katheryn Kiden

Mafia Trilogy 03 - The Scythe by Saul, Jonas

City of Hope by Kate Kerrigan

Silencer by James W. Hall

Kill All the Judges by William Deverell