Strange Light Afar (5 page)

Read Strange Light Afar Online

Authors: Rui Umezawa

I hear hushed voices over the hedge that evening. They are out in the yard, reminiscing about Shiro and how the dog loved to go for walks along the main road of town. I step outside but remain in the shadows as I draw closer. Sakura puts her loving arm around my brother's shoulders. Perhaps, they muse, they should not have buried Shiro at all. Maybe he would have preferred to be cremated, and to have his ashes scattered along the road.

They decide they could still do this with the ashes of the mortar. They laugh at how they both arrived at this idea at the same time.

The air is cold, though we're well into spring. The unseasonal weather is keeping the cherry blossoms from blooming this year. The trees' bare, twisted limbs hang over the road under the gray skies.

Jirobe walks with Sakura, holding her hand. I follow from a safe distance, slipping in and out from behind the trees. I think of how I was never visible to them anyway. Not to her, even though I have longed for her all my life. Not to my father. Not even to my wife.

Jirobe is carrying an urn full of ash. When they come to what they feel is an appropriate spot, he opens the urn.

A procession advances toward them. I see a gold palanquinÂ

â

an immense, ornate trunk slung on a pole carried by stern-faced porters. It clearly holds someone important. Jirobe hesitates, but a strong wind picks up as if it has been waiting just for this moment. He cries out as he loses his balance along with his grip on the urn. As it tips over, the wind scoops up the falling ashes and casts them high into the bare boughs of the cherry trees.

The foot soldiers in the procession, along with everyone else on the street, pause as the clouds part for the first time that day. The sunlight casts a heavenly aura around the small pink flowers suddenly blossoming on the trees on our side of the path.

The palanquin is placed on the ground and out steps the daimyo. He is a large man. His flamboyant kimono whispers as he walks about. His stern expression is made sterner by a thick moustache. But when he sees the flowers overhead, his face collapses in glee.

His laughter sounds like thunder. “Delightful! I had just been lamenting how the

sakura

trees were not flowering this year!”

As Jirobe stands dumbfounded, the daimyo motions to his procession, and his soldiers come forward to hand one gift after another to my brother and his wife. Before long, Jirobe and Sakura are trying not to fall as the silk robes, gold and lacquerware spill from their arms.

“But what of the trees on the other side of the path?” the daimyo asks. Jirobe looks at the empty urn at his feet.

All I know then is that I am running home as fast as my old legs can carry me. Those were my ashes, after all. They came from my hearth. I hang onto a sliver of hope for some fairness in the world.

Once home, I throw some ashes into an urn and immediately run out again. I am surprised to find myself running faster than I've run in years. Anger and terror and anguish tumble through my mind.

Why? Why? Why?

As I approach the main road, I see the

sakura

trees blossoming in the distance, swaying in the breeze.

The daimyo is still admiring the white-and-pink petals, and he turns as I approach. Without being told, I enthusiastically throw the contents of the pot into the air.

The ashes are just about to fall upon the bare branches when the wind suddenly changes direction. The daimyo and his soldiers unfortunately have their eyes wide open. My ashes never reach the trees and fall onto their faces instead.

They are instantly blinded. Some start choking, while others vomit. The villagers scatter in fear of what they know will follow.

The daimyo walks around with his eyes closed, shrieking like a monkey. A furious monkey who, when his eyes finally open, sees me petrified, clutching the empty pot as if it were the only possession I have left.

And so I have come to this place. My hands are bound behind me as they lead me to the courtyard of the local magistrate. Ahead of me is a samurai waiting in his traditional white kimono, his executioner's sword in its scabbard at his side. But it will not remain sheathed for long.

There is a crowd gathering beyond the open gate. I scan the faces for Jirobe and Sakura, but they are not there. They may be at the back of the horde, or they may not have bothered to come.

For the first time that I can remember, such a thing does not bother me. Even memories of my father do not stir any emotion.

I wonder if he would have cared at all where I wound up?

There is a straw mat in front of the executioner on which I will be made to kneel. The path to it, however, stretches like a snake. I seem to have all the time in the world. Enough time to think deeply about how things had been going so well, if only that cursed dog had not appeared. I had been enjoying passing the days in seclusion. I was even starting not to miss my wife.

They never did find her body, because I'd hidden it so well. And the villagers were all very eager to believe she would leave me. Not even Jirobe or Sakura suspected that I buried her in their yard, just a few feet from where they and that cursed dog found the treasure.

So, fairness has nothing to do with anything. There is no justice in this world.

The sun's warm rays caress my face. I am more content than I have ever been.

Beyond the gates and the restless crowd, I can see the cherry blossoms swaying in the breeze.

FIVE

CAPTIVE

â

H

e left his fish half-eaten like always. Carefully separating the leftover flesh from the bones with his large hands, he prepared three equal servings for his cats. Afterwards, he scooped a live smelt from a pail and threw it into the turtle pen by the window.

Finally, he replenished the dish of uncooked rice in the birdcage.

The sea was just beyond the hill, and on most days he could hear the waves crashing on jagged, unforgiving rock. Strong winds noisily brushed the branches of the high pines surrounding his secluded hut. Seagulls cried sadly throughout the day.

Hakuryo had stayed ashore that day to repair the fishing nets. He spent half the morning restringing gaps in the section he had hung across a few posts in the sand. He only went back to his hut for a brief meal, then resumed his work in the afternoon.

He did not realize until Saburo appeared from beyond the dunes that this was the day when he always bought kelp and dried bonito from the old vendor. Sabu somehow always knew what Hakuryo wanted and how much.

“Probably for the best that you didn't go out this morning,” the wrinkled man with dark, rugged skin said as he placed the bonito blocks on a cloth he had laid on the sand. He massaged his hip and straightened his back. “Wind's too high.”

Haku shrugged his mountainous shoulders and grunted. Sabu did not expect anything more.

Hakuryo only said what was necessary. No more or less. His father had been one of Saburo's customers a long time ago.

Haku's father had insisted on going out on a morning even more windy than this. Sabu still vividly recalled the colossal dark clouds that had gathered over the horizon at dawn. He had advised Haku's father to forget about the day's catch, but there were always debts to pay.

It turned out the storm collected another kind of debt that day.

Still, it was only when his mother also disappeared that Haku stopped talking. Sabu could not blame the woman for leaving a life that consisted of avoiding angry debt collectors. But why could she not have taken her boy with her? He knew the question bothered Haku every day. It was no wonder the boy had turned out so peculiar.

He also knew that others in town were not as compassionate in their view. Their idea of charity was just leaving the young man be. Everyone had their own troubles.

“Are you coming to the festival later?” Saburo asked, though he knew the answer.

Haku shook his head. The old merchant left, leaving a block of bonito and a stack of dried kelp tied with cord.

Music rode the sea breeze to Hakuryo's hut as evening fell. In the distance he could see the dim light of the bonfire he knew was blazing on the beach. Men and women would be dancing around it, drinking and flirting and drinking some more. The summer night was balmy and humid. The noise would continue until close to morning. Sleep would not be easy.

He rose and lit a fire in the brazier cut into the hut's floor. His cats purred as they nestled close. He scratched his favorite behind its ears and made sure the others were not ignored. The music and merriment swelled and permeated the walls. At the same time, the silence inside the hut was deafening.

After a while, he was overcome by a heaviness he could not explain. He stepped out into the warm breeze that stirred the darkness.

Haku looked up at the starless sky. The waves breathed in the opaque night. He felt utterly alone.

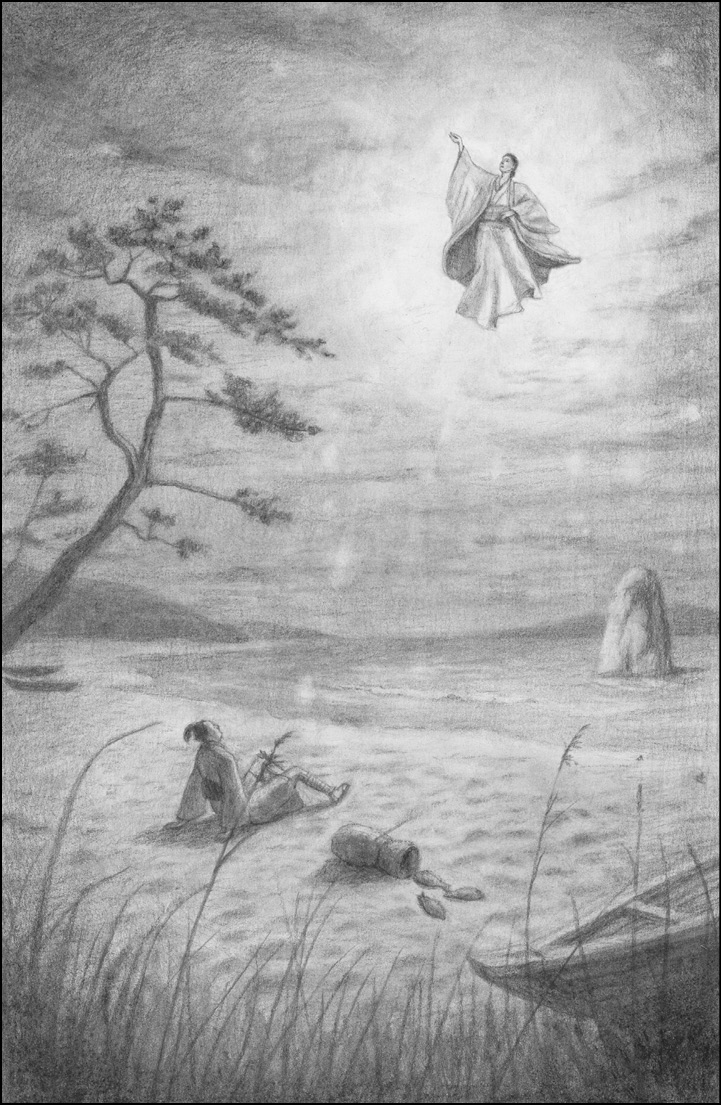

Something like a spark flickered on a pine branch overhead. He looked closely and saw something hanging on the gnarled limb, reflecting the faint light coming from the hut. He scurried back inside and emerged with a lit torch. Edging close to the tree, it took a moment for him to understand what he saw.

The robe was delicate and adorned with gold feathers that shimmered back at the flame. It fluttered in the wind but remained wrapped around the old tree branch like a fish caught in one of Haku's nets. He wondered how much the exotic fabric might be worth at the market.

He grasped the branch immediately below the robe and hiked himself high enough to take hold of the garment's hem. He unwound the robe from the tree and hopped back down onto the warm sand.

The fabric was light and the feathers soft. He smelled sweet incense when he held it to his face.

“Please unhand that at once!”

Hakuryo turned, startled. A woman with fair skin and long hair flowing like a silk river stood a few feet away. She was dressed in the formal kimono of a court maiden. Pleading eyesÂ

â

deep, dark pools that seemed bottomlessÂ

â

drew something warm and long forgotten from the hollows of his chest.

Then he remembered the robe.

“This is mine. I found it.”

“No, it is mine,” the woman asserted. “I merely hung it on that tree while I looked in on the festivities in your village.”

“So you say.”

Hakuryo rolled the robe under his arm before turning to go back inside. The woman followed him.

“Yes, I certainly do say, because that is the truth. Please give it back to me.”

Haku sat and poured himself a cup of well water. He tried not to look at her, afraid to weaken his resolve. Furtive glances were enough to see that her skin was as flawless as freshwater pearls, and her fine features glowed in the firelight.

Still, the robe remained firmly in his arm.

The stranger once again angrily demanded the return of the robe. Then she pleaded, as the fisherman impassively watched the fire.

“Please. You must give it back to me. I cannot return home without it.”

She said her name was Otoki. Although she was a celestial maiden who lived above the stars, she often liked to descend to earth to see how mortals occupied the short lives they were given. She had heard the villagers speak time and again of festivals and how entertaining they were, so she was compelled to see for herself. She used the power of flight accorded by the feathered robe to come down to earth.

Without it, however, she could not ascend back to the sky.

Others in heaven would worry if she did not return, she said.

Hakuryo feigned disinterest as he petted one of his cats. He refilled their water dish and checked the cage where the bird appeared to be asleep. Otoki smiled when a cat rubbed against her ankle. Animals always lifted her spirits.

Disappointment, however, fell onto her face when she saw Hakuryo prepare his bedding. Dousing the fire in the brazier, he tucked himself under a thin futon, the robe still rolled tightly under his arm. Otoki bit her lip and remained standing while the cats inspected her, puzzled.

Time passed slowly. The music from the beach eventually faded away.

Finally, she sat down in the corner of the hut and watched the fisherman sleep until morning. His chest rose and fell with the sound of the ocean.

Haku awoke to the smell of grilling fish. He saw that the brazier had been lit, and a couple of bluefish were cooking on stakes, their oily skin crackling. Otoki stirred a pot of soup above the flame, her hair tied neatly back. The whiff of bonito broth tickled Haku's nose.

They ate in silence. Otoki no longer badgered him about the robe. Haku held onto it firmly nonetheless, even though this meant he had to eat with one hand.

Later, as he set out for his boat, she told him, “I understand you have no reason to trust me when I tell you that the robe is mine. So I will tend to your needs until you see that I am an honest person. Perhaps then you will return my possession to me.”

Haku looked into the maiden's eyes. She tried desperately to maintain her composure and not burst into tears. His face softened, just a little.

“It was good,” he said.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Breakfast this morning. It was good.”

And with that, he was gone.

Otoki tried not to think about her home as she tidied the fisherman's hut. The cats seemed pleased when she fed them, and the turtle in the back pen quickly ate the shellfish she gave it. Surely someone who cared for so many animals must have a good heart, she thought. She would eventually convince him to return the robe to her. Of this she was certain.

The skies were clear but the winds were high. Otoki did not expect Hakuryo to return before evening, but he suddenly appeared at the door in mid-afternoon. The first thing she noticed was that he was soaking wet from head to toe. The second thing she noticed was that he did not have her robe with him.

Haku stumbled into his hut and sat down, out of breath. A dark cloud spread across Otoki's chest. Still, she fetched him a cup of water.

“I'm sorry,” he gasped as he drank. “I've lost your robe out at sea.”

Color ebbed from her beautiful face. It was her turn to sit down. He recounted how he feared letting go of the robe even for a moment. After what she had told him, he said, he thought it might even fly off on its own. So he cast his nets from his boat with just one hand. The waves were rough, however, and he lost his balance. He fell off the side with the robe still in his hand.

“When I managed to pull myself back onto the boat, I realized that I had let go of your robe. I looked for hours, but to no avail. It has likely drifted off or sunk.”

Hakuryo saw tears on Otoki's face for the first time. Short breaths fluttered as she tried to speak.

“I cannot ⦠I cannot go home. I have nowhere to go.”

The fisherman fell into his usual silence.

Over the next few days, Hakuryo tended to Otoki, who had fallen into a deep depression. He let her sleep as much as she wanted in his futon, only rousing her to feed her.

He prepared each meal with the deft skill and care of someone who had been cooking for himself for a long time. He boiled shaved bonito flakes along with kelp before mixing it with fresh miso. He sliced tuna, carefully avoiding the tendons, and arranged the pieces on a plate.

But she ate next to nothing. The cats were overjoyed with the abundance of leftovers.

Eddies of cold emotion swirled in Otoki as Haku tended to her. Time and again she thought of him and her robe on a wobbly boat. She could not believe his carelessness.

But what was done could not be undone, and he was clearly trying to make amends. He continued to go out to fish during the day but spent the evenings nursing her. He slept on the bare floor while she remained in his bedding. And he never once complained.

She found her anger slowly turning and receding like the tide. Her immortal elders had taught her the virtues of benevolence and forgiveness. These teachings returned to her little by little.

Then on a day when the seas were particularly calm, Hakuryo returned to his hut to find Otoki up and about. The hut had been tidied so neatly that he hardly recognized his home. And she told him it was now her turn again to cook for him.

Haku felt his knees give way. Kneeling at her feet, he sobbed into his hands and begged for her forgiveness.

“Forgiveness is already yours,” she told him kindly. “You must know that.”

Their lives quickly fell into a routine. He went on his boat each morning to fish and did not come home until late afternoon. She tended to the hut and the meals. Haku procured more bedding from the village, and they laid their futons side by side each night. He also brought home some clothing, and now she looked just like a woman from the village.

Sabu returned one day with more dried bonito and seaweed to sell. The old man's jaw fell when he saw an unfamiliar but beautiful woman cleaning the hut. Otoki inspected his merchandise and negotiated prices as if she had lived there for years.

The sun was already slanting toward the west, and Haku appeared before long with the day's catch. His heavy steps paused when he saw Sabu talking with Otoki over tea, but otherwise he did not react to the merchant's presence.

Otoki poured him his own tea.

“She is perfect for you,” Sabu whispered to Haku while Otoki tended to the animals. “Where did she come from?”

Haku sipped his tea in silence. He only betrayed emotion when Otoki opened the birdcage to clean it.

“Be careful!” he shouted. “Or it will get away!”

“Easy now,” Sabu said, resting a hand on Haku's shoulder. “Nothing to be upset about. She is only trying to help.”

Otoki smiled at them both.

She had grown content in her new role. She only felt a bit uneasy whenever she overheard Haku talking to his pets. It was not anything in particular that he said to the cats and the bird and the turtle. She only wished he would have as much to say to her.

Still, he was genuinely kind to her. He brought her colorful conch and abalone shells. He was attentive when she recounted stories about the heavenly palaces.

On the few occasions when she could not help crying as she reminisced, he was tender and understanding, brewing her tea and listening to her recall her life in a place higher in the sky than he could ever imagine.

They never spoke of how long she might stay. They both knew she had nowhere to go. He also knew he did not want her to leave.

Ribbons of early light spilled through thick clouds one morning after a heavy rain the night before. A light breeze brushed away the lingering humidity. Otoki closed her eyes and allowed the coolness to wash over her hair.

“You can stay as long as you'd like,” Haku finally told her. “Truth be told, I am hoping you will decide to live here with me forever.”

The implication of his words was clear, and she was surprised to find that they pleased her. Without another word, he draped his nets over his shoulder and left the hut. She watched his back disappear toward his fishing boat. His wide shoulders reminded her of a mountain range, silent and unchanging.

In heaven, she had been an immortal. Now, a life on earth with a man who cared for her was perhaps the best she could hope for. It was a life different from what she had expected, but one to which she was becoming accustomed.

Later that day, as she prepared the evening meal, she saw that they were out of kelp. She knew Sabu was not scheduled to come by for another week, so set off toward the village to find him.