Strange Light Afar (7 page)

Read Strange Light Afar Online

Authors: Rui Umezawa

I cannot allow myself not to be a part of it. I am as enlightened as any in the

sangha

, after all. Why should I not partake in this glory also?

“Ah!” I cry out. “Lord Shakyamuni Buddha! So beautiful! So revealing! There is nothing in life more meaningful than this simple flower! Praise be our master and all his wisdom!”

No sooner do I hear myself shouting than a dark shadow casts over everything in sight. The sky quakes, and a frightening, guttural roar echoes across the mountain ridge. Lightning suddenly strikes at the center of the crowd, which scatters, screaming. The winds rise as quick as anger. Rain and dust mingle around my eyes. I squint and see both Brahma and Mahakassapa run off into the distance, faster than anyone else.

As for the Buddha, all calm has drained from his face. His arms wave as he scampers off like the rest of his disciples. I notice for the first time that there is something vaguely familiar about him.

A bolt of lightning obliterates a rock in front of him, making him change direction. Another strike makes him turn abruptly again. The third seems to crush what little hope he might have of escaping, and he falls to his knees, sobbing.

“You dare?”

A voice deeper than the ocean shouts from overhead, and the ground trembles. I look up and nearly fall over when I see the towering figure of Indra, the god of rain and thunderstorms, his face scowling and full of rage. His skin appears as rough as animal hide. His sinewy muscles ripple with every movement as he descends toward the Buddha, who appears to have wet himself.

I might have been absolutely horrified had Indra not thrown another bolt of lightning at the Buddha, resulting in his transformation right before my eyes.

The heavenly aura around his head fades. His eyes shrink and become small black pools. His nose curves into a beak.

When the metamorphosis is complete, I am aghast to realize that he is not at all the Enlightened One but the same

tengu

who offered to grant me my one wish.

He looks at me angrily, sobbing.

“You fool! I told you not to speak! Did I not tell you to be absolutely quiet? Didn't I?”

“Silence!”

Both the

tengu

and I shrink into ourselves when Indra speaks. He looks down upon us, taller than the tallest pine.

“Foolish demon. How dare you assume the form of our Lord Buddha? Is there no limit to your insolence?”

The

tengu

remains on his knees, kowtowing wildly. He talks about me as if I cannot hear him.

“Forgive me, Master! I only wanted to teach this fool a lesson! He is the same idiot who put me in a cage half my size years ago. He kept vermin and other creatures in similar cages outside in all kinds of weather, often forgetting to feed us for days!”

What is this

tengu

going on about? I often marvel at how some people's memories are so unreliable.

Indra shakes his head, which is as large as a house, and extends his immense hand.

“Vengeance is far from a worthy cause, and certainly no excuse for your blasphemous behavior. Come with me and accept your punishment.”

“No!”

The

tengu

suddenly jumps to his feet, and before I can even blink, flies into a crack running down the face of an immense cliff.

I am dumbfounded. The crowd has dispersed, and now only rocks and boulders remain, scattered across the ridge. The sun reappears from behind the clouds. Indra stares for a while at the spot where the

tengu

disappeared, but finally shakes his head before turning to me.

“And what do you have to say for yourself, foolish mortal?”

I resent his presumption. I tell him I am an innocent victim who should be returned to his homeland in Japan.

“You are in Japan.”

“This isn't India?”

Indra throws his head back and laughs.

“No, my friend. I am afraid you are in Satsuma.”

I realize the stifling heat is due to the fact that I am now much farther south than where the

tengu

first spotted me.

“I still need help getting home. I am after all just an innocent victim duped by a misguided demon.”

“You are no innocent,” Indra laughs again. “You consider yourself selfless, but vanity is your greatest sin.”

The words tumbling from his mouth are completely meaningless to me. What is he going on about when he should be helping me to get home?

“I should reprimand you severely as well for not knowing your place, but your presumption amuses me. And your intentions, as misguided as they are, seem virtuous. I shall leave you here on this mountain and consider that adequate punishment.”

He bids me farewell and summons the funnel cloud that lifts him back into the heavens.

When the air stills again, I find the heat suffocating. Nothing but rock all around, and for the first time I fear dying of hunger and thirst. The mountain ridges stand against the scorching rays of the sun, defiant.

I consider Indra's words for a moment but then see a distant village across the valley below. If I am lucky, I shall reach it by nightfall. I shall ask for food and water and, in return, I shall impart to the villagers the story of how I encountered supernatural creatures who envied me for my capacity to love.

My legs find renewed strength when I consider how much this will be appreciated. I make my way down the mountain, humming as if I were once again a small boy.

SEVEN

PARADISE

â

M

y village is at the foot of a mountain, by the seashore. The meltwater flowing from the snow-capped peaks in springtime is perfect for brewing rice wine fit for gods. Where the mouth of the river meets the ocean is bed to a constellation of shellfish.

And the fish! Every season brings a bounty. Fatty yellowtail in winter. The barracuda are fine in the summer, raw with a touch of vinegar and soy sauce.

All this under a sky that is mostly blue with just the right amount of rain.

And yet, whatever the season, I can hardly drag myself from my futon in the morning.

My mother inevitably calls from the kitchen once, then twice. After three times, she stops. I would go back to sleep, except I can hear her muttering under her breath, which is worse than yelling.

It's my turn to yell when I see that she's hidden the sake again.

“But it's still morning,” she pleads. “Too early for rice wine.”

My anger feels like it belongs to someone elseÂ

â

someone who does not see the tears that trace the same tracks along the folds on her face every morning. Where is my sake? There is a vague sense of relief as my arms flail, throwing whatever it finds against the walls. Anger spills out of me. My rice bowl shatters against the frame of the door.

Then, as she does every morning, my mother brings me the hollow gourd that is my wine flask. The jagged edge of the morning is smoothed over after a couple of mouthfuls. I feel better and would apologize for my outburst, but there is no point. She knows our daily routine will repeat itself until one of us dies or runs away.

Any change would be a blessing. In the meantime, there is the sake.

I chew on grilled fish and pickled radish, but I have no appetite. Leaving half the breakfast she has prepared, I get up and walk to the door. My nets lie tangled in a heap. I lift the mess that still smells of fish, even though no fish has touched it for weeks.

“The boats are gone,” she says. “They cast off three hours ago. In fact, they'll probably be back soon.”

I know this. She knows I know this. I throw the nets on the floor and grab a fishing rod instead. She does not look up from clearing my plates.

The salt winds swell my breath when I step into the sun. The high branches of black pines sway and murmur. The fresh air clears most of the mist from my mind. I try to rid what remains with more wine.

Laughter drifts from the beach where a group of children huddle over a rock on the sand. As I draw closer, I see the rock inch toward the circle of feet.

One of the larger boys pokes the turtle with a stick. It retreats into its shell lazily and lies unmoving as the boys taunt and spit on it.

When an animal knows there is no hope, it smothers its own will to survive. Otherwise, life becomes too painful to bear. I've seen it in fish. I've seen it in nestlings that have fallen from trees.

And now there is this turtle.

The boys notice me.

“There's Taro!”

“What're you looking at, Taro?”

I draw closer. The turtle shell remains at their feet, unmoving. One of the runts pinches his nose.

“You smell like sake, Taro.”

“Don't you know it's still morning, Taro?”

I try to think of something clever to say.

“Shut up.”

“Oooh, one tough mama's boy.”

“Does your mama know you missed the boats again, Taro?”

From the way they talk, you would never guess that I am nearly twice their age and three times their size.

I push my way into their circle and pick up the turtle. I feel the tip of a stick poke my shoulder. I hear them snickering. A chill crawls down my skin like ants.

“What do you think you're doing, mama's boy?”

“I said shut up!”

I turn and scowl. One of them swings his stick at my bare ankle. The sting is sharp and focused at first. Then the pain dulls and spreads.

This almost feels good. Soon they're laughing and cursing and throwing stones at my back. Nothing hurts too badly. Ignoring them is easy. I press the turtle against my chest and leave them to look for something else to do on this day that is as empty as any other.

I walk along the beach, where the sand lifts, then falls in the wind. I place the turtle at the edge of the tide. The waves breathe. The soft ground below the turtle erodes, and the creature tips slightly into the water. The next wave takes it away.

I watch dumbly. The sake is nearly gone. The water laps at my feet as I lie down on the warm sand.

Time passes, and I drift into the void behind my eyelids.

“You can leave this place, you know.”

I sit up. The turtle has grown as large as a rowboat. Its voice is deep and soothing. It speaks our village dialect. It crawls slowly out of the water toward me.

I suddenly realize that I'm not afraid. There are times when my own lack of emotion surprises even myself. I did not cry when my father died, as my mother is fond of reminding me. The only emotion I ever express to her is anger. And I am angry at her every single day.

“Where would I go?” It is as though I meet talking turtles every day.

“I can take you to a beautiful palace I know. It's under the sea.”

“Then how can I get there? I don't breathe water.”

“You can ride on my back. As long as you have hold of me, you will be fine. There is no need to be afraid.”

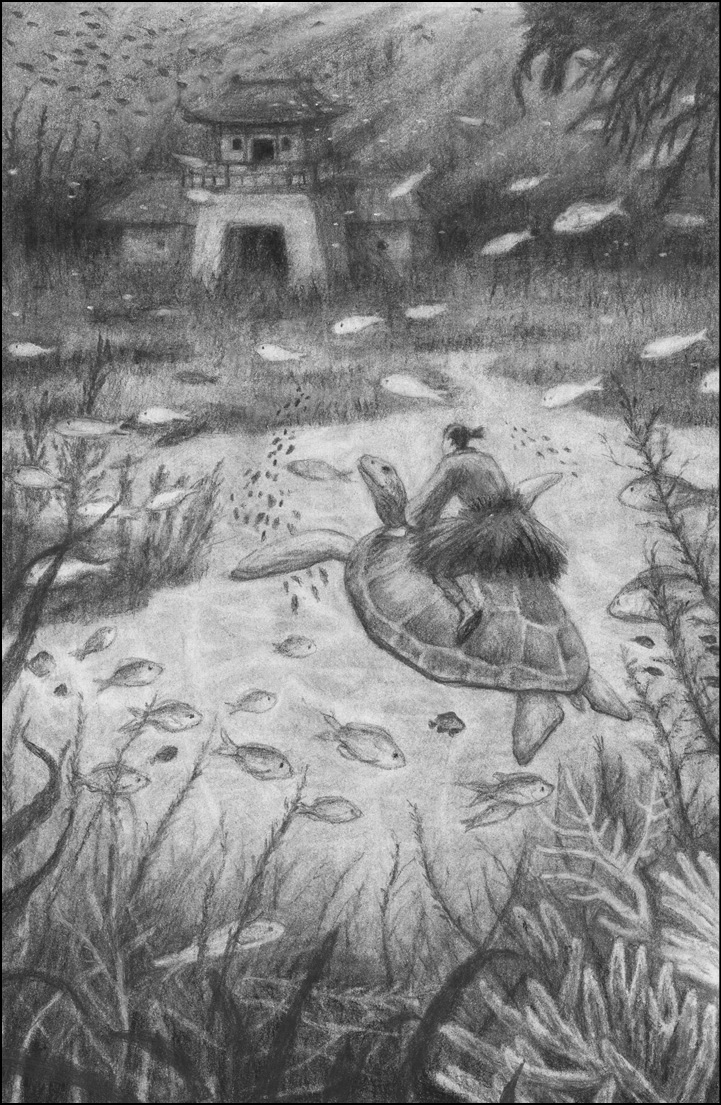

I honestly am not. There is so little to lose or fear. I think of my mother. I see her gathering what little food there is around the house for supper. I shake the image from my head before climbing onto the turtle's shell.

“Will there be sake?” I remember to ask too late, as we submerge under the white crests.

The sea is warmer than it has ever been. I can barely feel the water as schools of fish swim by. They do not seem surprised to see me. We swim over kelp growing among bright coral. Shellfish and crab stroll along the sea floor.

Hard to believe all of these creatures kill and eat each other to survive.

“We only eat what we need.”

The turtle speaks directly to my mind, which is how I understand that it can also hear my thoughts.

From the murky depths emerges a high wall that is made of crystal of all hues, glowing in the dim darkness. The wall is as high as a cliff, and I understand for the first time the depths we have reached. Underneath its jagged surface, luminous colors move and shift, fragmented light shimmering in the crystals.

The turtle calls it Ryugu Palace. I nearly fall off its shell when I realize we are on our way to the home of the Dragon King. He could have mentioned this earlier, I think. The Dragon King is said to capsize ships and feed on its sailors. I would not have been so eager to come to a place where I am considered a delicacy.

“There is no need to worry,” the turtle says, chuckling. “You are my invited guest.”

We approach an archway at the foot of the wall. An iron gate swings back slowly.

When we swim through it, I see that we are in a long corridor. At the other end, a light grows brighter and larger as we draw near. The turtle and I float upward, and we soon break the water's surface. I find myself in an immense hall lit with countless oil lamps, but the air is as fresh as it is by the seashore.

“You can get off me now.”

I hesitate. Despite my claim to have nothing to lose, my arms and legs apparently think otherwise. Slowly I coax one foot onto the edge of the pale marble floor, then the other. I regain my balance as the turtle laboriously crawls out of the water.

Iron columns support the ceiling. At the base of each one stands a bronze statue of an imperial guard clad in armor. The far wall consists of ornate screen doors that are shut. Gold carvings of turtles and fish reflect the lamplight.

A small moth flies about my head before I wave it away. I thirst for sake to calm my trembling hand. I think of my hollow gourd left back on the beach.

The screen doors suddenly part, and the Dragon King reveals only his head, which is large enough to take up half the chamber. His neck elongates its way to where I stand. His eyes are burning gold, peering at me curiously. Green scales glimmer, as jagged as glass fragments.

When he speaks, it is as if I am standing in a windstorm. His voice rumbles like an erupting volcano.

“Who is this?”

“A kind and virtuous soul, sire,” replies the turtle. I try to stand taller despite my petrified bladder.

“Hmm,” the king says. “If you say so. What is your name, young man?”

“T-t-taro.”

I feel like a fish about to be gutted.

“Well, Taro-san. I am glad you are here, especially if you are as virtuous as our friend here says. I have a daughter who is in need of human companionship. Her loneliness has robbed her of appetite and vigor. Why, it's now mid-day and I believe she is still in her bed chamber. I will have her sent down.”

It dawns on me that the turtle has not brought me here simply out of gratitude. A wall of warm air shifts as the immense head retreats. Reflections from the Dragon King's scales shimmer on the walls.

“Excuse me,” he says. “I have things to which I must attend.”

“I shall take my leave also,” the turtle says. “I hope you enjoy the comforts of the palace.”

It drops back into the water and sinks into inky darkness.

I am left alone. I try to puzzle over what has just been said. The Dragon King seems to want me somehow to tend to his daughter. How does a human tend to a dragon?

However, it is clearly a human woman who now appears from behind the screen doors. She is gently attractive. Her brightly colored silk robe flows around her hips and shoulders as if alive. She seems as perplexed as I am.

“My name is Oto. My father has instructed me to offer you respite and refreshments. Please follow me.”

We move to a room where a large table holds countless delicacies, many of which I have never seen before. There is fresh sashimi of vibrant red and pink. Bowls of dark kelp garnished with carrots and daikon radish. Sticky rice steamed with red beans.

She motions me over to a chair. The heavy wooden arms have been carved into dragons with their mouths gaping. She stands over my shoulder and pours me a cup of sake.

I have never tasted anything quite like it. A sweet fruity fragrance overwhelms the slight pinch on the tongue. The subtle flavor wraps around the piece of fish that slides between my lips. Fresh tofu blends with savory soy sauce and ginger.

Oto pours me another cup of wine. The fish my mother grilled for me just that morning becomes a forgotten, insignificant dream.

Oto sits across the table and relaxes, even smiling quietly every time I show surprise at each new delicacy.

I say I would have been nicer to more turtles had I known what would come of it. She laughs for the first time. We talk. She tells me how each dish was prepared, and which are her own favorites.

“How did you come to be here?”

She pours herself some sake, then takes an elegant sip.

“My father is the elder of a fishing village probably very similar to yours but far to the south. Some years ago, I was put on a ship to travel to a neighboring island where I was to wed. When our boat capsized in a sudden storm, everyone drowned, but the good Dragon King rescued me. He has treated me like his daughter ever since.”

“But don't you wish to return home?”

“I often consider it, but in truth, the village where I was born has not been my home since my wedding was decided. And my intended new home is a place I have never seen. In a way, I feel things turned out for the best. There is food and shelter here. And now I have your company.”

She smiles again. She brings more food and continues to pour the sake until I beg her to stop.

No one awakens me the next morning. No one shouts in my ear or pulls the covers away. I swim in the delicious warmth beneath my futon, my eyes closed, unwilling to let go of the darkness. It occurs to me between fits of dreams that I am not hung over in the least. My mind floats in a carefree quiet until pangs of hunger pull me toward the light.

I emerge from eddies of wrinkled bed sheets. Oto immediately appears carrying a tray of food. A cloud of steam rises from the bowl of rice soup. The hot gruel seasoned with sea salt and ginger has been poured over slices of raw yellowtail tuna and scallops, half-cooking their tender flesh. Pickled radish lies on a side plate.

To my delight, she has brought sake with breakfast.

“I can't thank you and your father enough for your hospitality.”

“It is our great pleasure. I hope you can stay with us for a few days.”

I consider this for a moment, then shake my head sadly. “I am afraid my mother will be worried.”

“Oh, but you must! You have not yet seen the rest of the palace or tasted all the delicacies our kitchen has to offer.”

I agree to stay for another day, but insist I cannot stay any longer. I have work to do at home, after all. Oto claps her delicate hands in delight.

Later that morning, she takes me for a stroll through the palace. Then we eat some more. I drink. She tells me of her home village. The salty sea breeze. The long sunsets beyond the flat horizon. Children's laughter always in the wind.

It sounds awfully like my own village. I pour myself another drink.

Just when even the food, the sake and the playful fish swimming by the windows start to bore me, animated marble statues of musicians and dancers enter the chamber where we are lounging. Melodies like colorful corals weave through the room. Mimes tell of ancient legends that reveal the mysteries of the depths. Laughter comes in waves, over and over.

I awake the next morning to find Oto's hand stroking my face. Pinpricks of light swim on the ceiling as the sea turns and twists beyond the window. Her smile is as soft as her face, which is warm to the touch of my fingers. She squeezes my hand in hers, then stands and brings over another tray of food.

I briefly imagine my mother's worried face.