Stuck in the Middle With You: A Memoir of Parenting in Three Genders (12 page)

Read Stuck in the Middle With You: A Memoir of Parenting in Three Genders Online

Authors: Jennifer Finney Boylan

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Lgbt, #Family & Relationships, #Parenting, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Gay & Lesbian

A month shy of his sixth birthday, DJ came to live with Emily and me.

JFB:

Now I know this is a painful question, but could you talk about what DJ’s life was like before the age of three?

RJS:

His birth mom was very poor. Her husband had left her. She had very serious drug and alcohol problems, was perpetually homeless or living in very, very subpar housing, and was working on and off as a prostitute. I mean, it’s difficult to speak about because—when DJ was attacked in foster care, it later became apparent that he had been sexually abused as well.

JFB:

Had you always wanted to be a father? Or had you decided—long before that moment when DJ banged his forehead against yours—that being a parent was not for you?

RJS:

I had, and still have, a terrible relationship with my own father. I was pretty convinced that I didn’t want to have children. The notion that I would father an autistic child, I mean,

fatherhood

? Are you kidding me?

JFB:

And yet suddenly you’re the father of a severely autistic boy. How did you figure out what to do?

RJS:

First of all, my wife is absolutely amazing. She knows a ton about autism, but more than that, she’s got a kind of Buddhist, still-water-runs-deep kind of calm. Having her model a way to act with DJ was really, really important.

Let me be clear: This is the hardest thing I have ever done. It’s been incredibly demanding; it’s involved enormous sacrifices. But it’s also been the richest thing.

DJ has had a life, and that life sustains us.

JFB:

He’s had a life because of you.

RJS:

I don’t want to sound like some sort of super-good person; I’m radically imperfect. But sometimes I think about where DJ would be now if we hadn’t adopted him. I think about all of the kids our society writes off as having no potential or as being unworthy of love.

Last June my son graduated with highest honors from Grinnell High School and is now off to Oberlin; at six he had been labeled profoundly retarded.

JFB:

How did you teach him language?

RJS:

Imagine a sentence in which every word has Velcro on the back and a word bank to the right of the sentence. Emily would start very, very simply with a picture of a car—a yellow car—whose caption read, “The man got into the _________________ car.” The word bank would contain the words

yellow, red

, and

green

. Emily would pick up the word

yellow

and place it in the blank, pointing at the photograph and modeling both the cognitive and motor actions. She would then have DJ do this. Every object in our house had a photograph, a computer icon, an American Sign Language sign, and a word attached to it. We wanted to immerse DJ in a signifying universe. To say that it was slow going would be an understatement.

But when he finally cracked the code of reading in the third grade, he moved like lightning. Later, he said that the feeling of picking up the Velcro-backed word and palpably putting it into the sentence helped him.

JFB:

Could you tell the story of the trampoline?

RJS:

We began to sense the degree to which DJ seemed to learn more quickly if he was in motion. I convinced Emily to buy a fourteen-foot

trampoline with a netted enclosure. First and foremost, it was a way to wordlessly bond with him and, frankly, to tire him out so that he would sleep at night. Later, we would tie words to the netted enclosure and really make the jumping an affect-laden, cognitive learning activity.

I ended up building an indoor trampoline house after we moved to Iowa, where the trampoline is level with the floor. It’s a six-hundred-square-foot building heated by a woodstove. We jumped every single day, all through the winter.

There’s a karaoke machine, which of course has words on it, and we would sing the songs while jumping and try to get DJ at least to hum them. To this day, he talks of how important that was.

Something about the regular rhythmic bouncing, the proprioceptive input the trampoline gives his body, stabilizes or calms the sensory distortion. It’s as if he were catching a performance-enhancing ride—a taxi with rhythm.

JFB:

So tell me about when DJ began to use the computer to type out words and to express himself that way.

RJS:

The first real breakthrough came when he was reading

Jack and the Beanstalk

at school. DJ had a label-making machine that he used for worksheets, and on this worksheet he encountered an open-ended question about the story’s conclusion: “What are Jack and his mother thinking?” To our everlasting shock, he typed,

Where a Dad?

He was clearly using the story to ask a profound question about his birth family. And then he started getting the hang of grammar, of word choice—all of those things.

I remember DJ’s answer to the question “What is a pyramid?”

A sand triangle

, he typed. “What is a mausoleum?”

Dead people live there

.

Later, text-to-speech software gave him a sense of empowerment. He could now contribute to class discussions. It empowered him to say, “Maybe I

can

learn to speak.”

JFB:

And he did it simply by typing with one finger, right?

RJS:

One finger. Interestingly enough, I typed the book that I wrote about DJ,

Reasonable People

, with one finger—all 496 pages of it! I just sensed that I’d be closer to his way of seeing the world.

JFB:

One of DJ’s favorite expressions is

easy breathing

, which reminds me of a line from Keats, from that poem “A thing of beauty is a joy forever.” That phrase came out of a stressful situation, if I remember right?

RJS:

He loves the phrase

easy breathing

because he has lots and lots of anxiety—in part from his autism and in part from his childhood trauma. And, I must say, in part from living in a terribly stigmatizing world. It’s a big deal to try to stay calm.

His philosophy of life can be summed up by a memorable line from the sixth grade: “Reasonable people promote very, very easy breathing.” He’s sort of like an anxiety seismograph.

I remember at one point he was having some dental work done, and he had been anesthetized. He seemed to wake up very, very slowly and it was making me nervous. When he was half or three-quarters awake, he typed out on the labeler, “Easy breathing forever.” It took being anesthetized for this boy to feel at peace!

JFB:

How will your life change when DJ goes to college?

RJS:

I don’t think I fully appreciated until now how much I enjoy hanging out with him, conversing with him, hearing his little autistic chorus in the background. I am going to miss him terribly. We’re very close.

DJ loved the fact that Oberlin admitted the first female and African-American students in the U.S. He wanted to be its first nonspeaking student—and the first nonspeaking student

anywhere

to live in the dorms. He worked like crazy to get into this school, and so we said, Let’s figure out how to do it.

Look at what this kid has shown is possible.

When Dr. Sanjay Gupta asked him in an interview on CNN, “Should autism be treated?” DJ had the presence of mind, and media savvy, to type out, “Yes, treated with respect.”

JFB:

What advice would you give to dads out there in the broad world? What do you know now that you wish you had known before?

RJS:

Love your kid for who he or she is. Build self-esteem.

It’s pretty common for the parents of newly diagnosed autistic kids to go through a grieving process. I tell them: Don’t waste time. Your

culture has taught you to believe that autism is devastating and that you’ll never get the love you want as a parent.

For Father’s Day some ten years ago—I still have the card on my desk—DJ typed:

Dear Dad

,

You are the dad I awesomely try to be loved by. Please don’t hear my years of hurt. Until you yearned to be my dad, playing was treated as too hard. Until you loved me, I loved only myself. You taught me how to play. You taught me how to love. I love you

.

Your Son, DJ Savarese

If I had remained attached to normalcy, I would have missed the richness that comes in another form. So love your kid. Make it a little bit less about you, and you’ll be able to relax about who he or she is.

And have easy breathing forever.

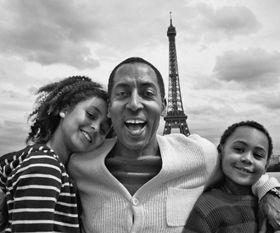

TREY ELLIS

Courtesy of Trey Ellis

How can a woman compete for the oceanic love I feel for my two soft miniatures?

Trey Ellis

is the author of three novels, including

Platitudes

and

Right Here, Right Now

, which received an American Book Award. A professor at Columbia University, for years he wrote the

Father of the Year

blog, about his experiences as an African-American single father. We first met in 1981, when we were both young writers working on

American Bystander

magazine. Thirty years later, on the night before Ellis’s forty-ninth birthday, we met in the Columbia Student Union, two old friends surrounded by young people.

J

ENNIFER

F

INNEY

B

OYLAN:

Do you remember

American Bystander

, you and me and all those young writers, the early eighties in New York? The magazine that was supposed to make us all rich?

T

REY

E

LLIS:

It was funded by the original cast of

Saturday Night Live

.

JFB:

Although we never saw them. I met John Belushi one time. I remember I went to the editor’s house, and Belushi was there. And he threw me up in the air, and he caught me. And he said, “There you go, kid,” and then he left. That’s my whole memory of John Belushi, being thrown in the air.

TE:

Well, at least he caught you.

JFB:

Our friendship was the friendship of young men in their feckless twenties; there was so much we didn’t know about the world. Back then, were children on the radar for you? Did you always think to

yourself, “Someday, I’m going to be that guy who’s going to have a great family”?

TE:

No, I didn’t. My own parents fought all the time. The house was just a sad, crazy, dysfunctional marriage. I never saw them once kiss.

So, I never had a real relationship to observe and model after when I was a kid. I just invented relationships, these perfect things, in my imagination.

JFB:

Is that how you became a romantic?

TE:

I’m a sap.

JFB:

Did that make it harder to find a relationship, after your wife left you, and you found yourself a single dad with two tiny children?

TE:

Yeah, because, in some ways, there’s something infantile about sappiness. I started dating so late that everything was all virtual for me. The romantic has blinders to the complications of life and thinks, Yeah, I should be able to find a woman who is just perfect and everything is uncomplicated. She’s a great mom, and she’s great in bed, and she’s a great cook.

But life isn’t like that. That’s part of growing up. With my new wife, it’s like the Grace Jones line, “I’m not perfect, but I’m perfect for you.”

JFB:

In your memoir

Bedtime Stories

, you write about the loss of your first marriage and about your time as a single father after the divorce. But there’s a fairly long stretch in the middle when the marriage seems doomed—at least to your readers—and you’re still trying to make it work. You make room for her new Rasta boyfriend; you try to have an “open relationship.” I thought of the line in Thurber, “Sometimes it is better to fall flat on your face than bend over too far backwards.”