Summer of '68: The Season That Changed Baseball--And America--Forever (27 page)

Read Summer of '68: The Season That Changed Baseball--And America--Forever Online

Authors: Tim Wendel

Tags: #History, #20th Century, #Sports & Recreation, #United States, #Sociology of Sports, #Baseball

A year after dominating the Red Sox in the ’67 World Series—in which he hit .414 and stole seven bases—Brock was back at it against another American League foe. He wasn’t satisfied with merely getting on base, however. He wanted to excel at all facets of the game.

“Look at Ty Cobb,” Brock said. “He stole 892 bases but people say, ‘Hey, Ty Cobb got 4,000 hits; he must’ve been a great hitter, too.’

“But what do people say about Maury Wills now? They say, ‘That guy, Maury Wills, stole 104 bases one season. He must’ve been fast, good on the bases.’ When I leave the game, I want to be remembered as a complete ballplayer—not only as a good base-stealer. . . . If you leave the stats in the record book, they speak for themselves.”

Speed can unnerve the best of opponents. With Brock on second and Curt Flood up, Wilson hurried his delivery, slipping as he followed through to the plate. Tigers’ catcher Bill Freehan called time and spoke with Wilson on the mound. While the Detroit starter admitted that he may have pulled a muscle in his leg, he was determined to get out of the inning. Yet when Flood doubled, bringing around Brock, and Roger Maris then walked, Smith had no choice but take Wilson out of the game.

The manager’s reasoning behind flipping Wilson and Mickey Lolich in the postseason rotation had been to have Wilson’s bat in the lineup at the smaller Tiger Stadium. But with Wilson now sidelined, the better-hitting pitcher had gone just 0 for 1 in Game Three, while Lolich had hit his improbable home run in Game Two at Busch Stadium.

“Is there any way to stop Brock from stealing,” Smith was later asked.

“Sure,” the Tigers manager replied. “All we have to do is play without bases.”

Right-hander Pat Dobson relieved Wilson, and after he got Orlando Cepeda to pop up he served up a three-run home run to Tim McCarver. In the span of five hitters, the Cardinals had taken a 4–2 lead. “That’s how quickly the Cardinals of that era could strike,” baseball historian William Mead said. “They always had speed with Brock and Flood. The pitching with Gibson and the others was there. The defense was excellent, too. So when the power came around for them, it was a very potent combination and pretty much unbeatable.”

Less than a month after pitching a no-hitter against San Francisco, Ray Washburn went just one inning longer than Wilson. Yet that was good enough to secure the victory on this blustery afternoon in downtown Detroit. “It was cold out there,” Washburn said of the temperatures in the mid-fifties, “but it wasn’t that bad. My control of the curve just wasn’t good. It’s the worst my control has been in some time.”

In the bottom of the fifth inning Dick McAuliffe launched a solo homer off Washburn that pulled the Tigers within a run, at 4–3. When Washburn walked Horton and Norm Cash with one out in the sixth, it looked as though Detroit was on the verge of another signature comeback. But St. Louis manager Red Schoendienst lifted Washburn and called on reliever Joe Hoerner of fungo bat fame. Hoerner snuffed out the rally, along with the Tigers’ hopes of winning Game Three, retiring Jim Northrup and Freehan.

In the top of the next inning, the Cardinals’ Cepeda blasted a three-run shot off Detroit reliever Don McMahon. The home run was Cepeda’s first in sixty World Series at-bats. With some daring-do on the base paths, coupled with a pair of home runs, St. Louis had jumped out to a commanding 7–3 lead. “Even now I can close my eyes and still see innings like that in my head,” Cepeda said. “It was beautiful what we could do sometimes. When it all came together for us.”

On the other side, everything came unhinged for the Tigers’ bullpen, a cruel reminder of the final days of the ’67 season, when another championship had been within their grasp only to slip away. After Wilson allowed three earned runs in four and one-third innings, Dobson quickly gave up another earned run in two-thirds of an inning. McMahon was rocked for three runs in an inning and John Hiller serving up four hits in his two innings of action.

Through it all, Detroit rookie pitcher Jon Warden stayed loose, ready to pitch. But he never got into the ballgame.

After the Cardinals’ 7–3 victory, McLain couldn’t help thinking that the Tigers “were cooked.”

Just like that, whatever momentum Detroit had gained by winning Game Two appeared to be lost.

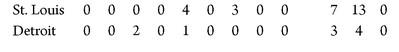

FINAL SCORE, CARDINALS 7, TIGERS 3

St. Louis leads Series, two games to one

October 6, 1968

Game Four, Tiger Stadium, Detroit, Michigan

The rain came down in buckets, reminding Gates Brown of that Beatles song they played on the radio. The one with the chorus that stretched out the word itself, “Raaaaiiiaaaiiiaaaiiinnnn, I don’t mind.”

Baseball commissioner William D. Eckert likely didn’t have such lyrics running through his head on this gloomy Sunday afternoon in Motown. Before the game, he walked the field and stared up at the heavens, as if asking for divine intervention. Clearly none was forthcoming as the rain continued to fall.

Across the country, everybody was talking baseball, eager to tune in for round two of the “Great Confrontation” between Bob Gibson and Denny McLain. On the presidential campaign trail, Richard Nixon, much more of a football fan, couldn’t resist a baseball allusion or two. In a stop in Hempstead, New York, he noted that Bob Gibson stuck out seventeen batters in Game One, adding, “This administration has struck out for America. It struck out on peace aboard; it struck out on peace at home; it struck out on stopping the rise in crime and it struck out in stopping rising prices.”

In comparison, Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey took the afternoon off to attend the game, now ready to cheer for the hometown Tigers. In both clubhouses, the players expected the game to be played at some point, no matter how hard it rained down on Tiger Stadium. “Too many people watching on TV, too much money to be had,” Gates Brown recalled. “No way the big bosses would pass that up.”

After a thirty-seven-minute rain delay, the pivotal Game Four began in the darkness and mist. On its biggest stage, with so many tuning in, baseball was about to give itself another black eye. Once again many in sports would blame Eckert, pointing out it was the second major decision of the season he had whiffed mightily on. Usually the umpires have the final say on weather—if a game will be played or not, or when it would be stopped. But for World Series play, the commissioner decided he would make the final call.

“For 162 games a year we’re permitted to decide rain or shine whether a game is going to be played,” umpire Jim Honochick told pool reporters Milt Richman of United Press International and Murray Chass of the Associated Press. “Then suddenly along comes the World Series games and they take it away from us.”

Before the rain came, Al Kaline had been concerned about facing Bob Gibson at Tiger Stadium. He couldn’t help worrying about how the shadows usually fell down over the field late in the day, and how Gibson’s blazing fastball would be coming right out of that darkness. Of course, with the rain and overcast conditions shadows weren’t the issue on this day. Still, Gibson promised to be a formidable foe. He didn’t mind pitching in the rain. On May 22, he battled the elements for eight innings while narrowly dropping a 2–0 decision to the Dodgers’ Don Drysdale (the third consecutive shutout in Drysdale’s record-setting streak).

In comparison, the Game Four rain delay and slippery conditions created havoc with McLain’s pregame preparations. The Tigers’ right-hander used the extra time to take a hot shower, trying to loosen up his sore right shoulder. Yet by the time the game actually started, it was no good. “I’m not a mudder, and Game Four was as bad as it gets,” McLain said. “When I walked out for the first inning, it was drizzling, and when I threw the first pitch, it was coming down in buckets. Actually, the first pitch went OK. It was the second pitch that (Lou) Brock hit into the center-field stands four hundred and thirty feet away.”

The Cardinals tacked on another run when McLain stumbled trying to cover first base on Roger Maris’s dribbler and then Mickey Stanley couldn’t come up with Mike Shannon’s grounder deep in the hole. At the end of the first inning, the Cardinals held a 2–0 lead, and the skies showed little chance of clearing. For McLain, the fun-loving days of summer seemed long ago.

In the third inning, the Cardinals doubled their total against McLain. Curt Flood singled and came around on Tim McCarver’s triple. McCarver then scored on Mike Shannon’s double. After Julian Javier walked, the rain began to come down even harder and home plate umpire Bill Kinnamon suspended play. While commissioner Eckert would be the final arbitrator if the game was called or not, Humphrey had already cast his vote. After joining Eckert in the commissioner’s box for early innings, the presidential candidate ducked and ran for cover.

By the time Bob Gibson appeared in his second consecutive World Series in 1968, opposing players had learned never to get the Cardinal’s ace hot under the collar. One would have thought fans would have gotten the message, too.

The year before, on the eve of Game Seven against the Red Sox in Boston, Gibson had tried to share breakfast with teammates Tim McCarver and Dal Maxvill and the players’ families at the Sheraton Motor Inn in Quincy, Massachusetts. Everyone else’s order promptly arrived, except for Gibson’s. After forty-five minutes, and several complaints, the waitress brought out burnt toast for the Cardinals’ ace.

“This toast is burnt,” Gibson told the waitress. “Please take it away.”

“We’ll take you away,” the waitress replied.

Gibson got by with a ham-and-egg sandwich, purchased by the

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

’s Bob Broeg at a diner near Fenway Park. Gibson won Game Seven over the Red Sox’s ace Jim Lonborg. “It was evident by that time, and to my good fortune, that Boston didn’t understand me,” Gibson wrote in his autobiography. “Anger was a part of my preparation. The people at the hotel, despite their best efforts to the contrary, were getting me extremely ready for the ballgame.”

A year later, in their own sweet way, Detroit fans did their part to assist Gibson in his game preparation, as well. The night before Game Four, after taping

The Bob Hope Show

with McLain of all people, Gibson returned to the team hotel in Detroit around midnight. At two in the morning, somebody hammered on his door yelling, “Telegram.” When Gibson opened the door, nobody was there. An hour later, the telephone rang. When he picked it up, the person on the other end of the line asked, “Is Denny McLain there?” and promptly hung up.

After a fitful night, Gibson awoke to find the hallway outside his hotel room decorated with flowers. Within baseball circles, flowers are considered bad luck, especially before a big game.

Gibson took such abuse in stride, however. While McLain was busy soaking his aching shoulder in a hot shower during the rain delay, Gibson ate an ice cream cone and worked on a crossword puzzle in Tiger Stadium’s visiting clubhouse.

After a second rain delay, this one lasting an hour and fourteen minutes, Game Four continued. But Denny McLain was no longer involved as Detroit manager Mayo Smith lifted him for right-hander Joe Sparma. The Tigers’ starter had lasted only two and two-thirds innings, giving up four runs, three of which were earned.

Of all the characters on the Tigers’ pitching staff, Sparma was the one nobody could really figure out. He possessed perhaps the best fastball on the ballclub, coupled with a hard-breaking overhand curveball. A well-rounded athlete, he played quarterback for Woody Hayes at Ohio State, keying the Buckeyes’ 50–20 victory over rival Michigan in 1961. Yet despite all the tools, Sparma was inconsistent at best on the mound. Perhaps it seemed only fitting then that he would be called on to throw in a ballgame that would soon turn into a fiasco.

“Rain, rain, rain,” the Tigers’ fans chanted, eager for the game to be called due to the weather. Their ranks on this blustery afternoon included actor George C. Scott and his wife, actress Colleen Dewhurst. Despite the outcry, commissioner Eckert ordered the infield tarp rolled up and the game continued. As the sporting world watched, baseball once again made a mockery of itself.