Summer of '68: The Season That Changed Baseball--And America--Forever (31 page)

Read Summer of '68: The Season That Changed Baseball--And America--Forever Online

Authors: Tim Wendel

Tags: #History, #20th Century, #Sports & Recreation, #United States, #Sociology of Sports, #Baseball

When asked about being booed by the St. Louis crowd, fans known for their courtesy and civility, McLain smiled and proved that redemption was perhaps on his mind, after all, “I’ve been booed before and I’ve been booed by better fans than these. I’ve been booed by the best fans in the world in Detroit.”

In his post-game press conference, Tigers’ manager Mayo Smith said, “We were down three to one and we’re happy to be going against Mr. Gibson.”

Then he officially announced what everyone expected: Mickey Lolich would start Game Seven for Detroit. The left-hander, like McLain, would be pitching on short rest. Little brother was going have his chance to be the hero. All he had to do was figure out a way to do what McLain and the rest of the Tigers couldn’t—find a way to beat Bob Gibson.

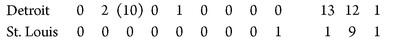

FINAL SCORE: TIGERS 13, CARDINALS 1

Series is tied at three games apiece.

October 10, 1968

Game Seven, Busch Stadium, St. Louis, Missouri

Before Game Seven, several of the Tigers players hung a SOCK IT TO ’EM sign in the visiting clubhouse. The saying was a popular refrain from

Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In

, one of the most popular shows on television, along with

Gomer Pyle, Bonanza,

and

Mayberry R.F.D

. Part rallying cry, part inside joke, SOCK IT TO ’EM summed up the Tigers’ dilemma in going against Bob Gibson again—this time in a winner-take-all.

As scribes eyed the sign, McLain told them that he would join Pat Dobson, John Hiller, Joe Sparma, and Jon Warden in the Detroit bullpen, where he would be “trying to put together a comedy act.”

Manager Mayo Smith explained that he was “not a good psychologist, so he wasn’t sure if his pregame conferences with Norm Cash, Bill Freehan, Dick McAuliffe, and Willie Horton did much good.” As for Gibson, Mayo added that the Cardinals’ ace “is not Superman. He’s beatable.” But his heart didn’t appear to be in such an assessment as he soon added, “But even if we don’t win, we’ve had a hell of a year.”

The capacity crowd in St. Louis gave Gibson a standing ovation after he finished warming up. As was his habit, the Cardinals’ ace stared straight ahead, barely acknowledging the overwhelming show of support. “It was down to me and Lolich in Game Seven,” Gibson wrote in his memoir. “I thrived on this sort of situation—to me, it was the whole reason for being an athlete—and there was no sense of panic on the club even after the disasters of Game Five and Six.”

Over in the Tigers’ bullpen, as Lolich prepared to take the mound, things were far less certain, even bordering upon the chaotic.

“Nobody was sure how far Mickey would go in the game—two, three innings? Nobody really knew,” Jon Warden said. “So everybody was up, doing a little bit to get loose. It was all hands on deck and nobody was sure when they could be going in.”

But as teammates stole glimpses at Lolich, they saw that he was throwing loose and easy. More importantly, his ball exhibited great pace and movement. “I felt fine,” Lolich said. “I wasn’t issuing any guarantees on how many innings I could go. Nothing like that. I was just going to pitch until I wasn’t effective. No more, no less. That kind of freed me up in a way.”

While McLain’s arm had received a shot before his recent victory, Lolich benefited from deep massage. Earlier, back at the team hotel, Dr. Russell Wright rigged up a shock-wave machine for Lolich’s tired left arm. “It was one of those crazy looking machines that look like something out of a

Frankenstein

movie,” the pitcher explained. “It increased the circulation in my arm and left me relaxed.”

With that and a few sleeping tablets, Lolich got a nap and woke ready to pitch. It was time for him to face his own Great Confrontation.

As expected, Bob Gibson came out strong and once again dominated, breaking Sandy Koufax’s single-series World Series record for strikeouts in the second inning. Through six innings, Gibson had sat down twenty of the twenty-one Detroit hitters he had faced. “I firmly believed that if I could hold the Tigers in check awhile, we would get to Lolich by the sixth or seven (inning),” he recalled. “Things were going pretty much as planned, but it was high time to do something about Lolich.”

Though not quite as impressive, Lolich somehow matched the Cardinals’ ace, zero for zero, on the scoreboard. Through five innings, he had allowed only two singles.

“Frankly, I don’t know how I got to that point in the game,” Lolich said. “I wasn’t feeling that good really. Every time I got back to the dugout, I told them to make sure to have people warmed up and good and ready. I didn’t know how long I’d last.”

In the bottom of the sixth inning, Lou Brock singled to left field and everybody in the ballpark knew what was coming next. Brock would try to pick up his eighth steal of the Series. Tigers’ catcher Bill Freehan went out to the mound to talk to Lolich, resulting in perhaps one of the most curious conversations in Fall Classic history.

“You all right?” Freehan asked his pitcher. “Anything I can do for you?”

“Yeah,” Lolich replied. “Can you get me a couple of hamburgers between innings?”

“What’s the matter?” Freehan said.

“Can’t get myself together,” Lolich explained. “I don’t know what I’m doing wrong.”

Usually Freehan didn’t coach his pitchers, especially in the middle of a contest as intense as Game Seven. He left that up to legendary pitching coach Johnny Sain. But with no burgers on hand, and the whole world watching, Freehan decided to throw in his two cents’ worth. The Tigers catcher suggested that Lolich was trying to throw too hard. He told him to keep his front shoulder in, instead of rearing back too much. “Just try to throw strikes,” Freehan said, “and you’ll still get good velocity from there.”

Through it all, Brock remained patiently, for the moment, at first base. Often when he would take off for second base he would beat the relay throw from the first baseman. The key to stopping him was to have Brock make the first move, to briefly hold him in his tracks, which didn’t allow him to reach full speed in a hurry.

With the conference over, Brock edged off first, taking a fifteen-foot lead, ready to break for second. Lolich kept an eye on him, refusing to deliver the ball to the plate. It was a showdown, reminiscent of the old-style Westerns that were so popular on television. Who would draw first? That’s when Lolich suddenly snapped a throw over to Detroit first baseman Norm Cash. And Brock took off for second base. At the time, many in baseball felt he was the fastest man on the base paths. Still, there are times to run and times to stay put.

“I really don’t understand why he did it,” Cash said. “That was too much of a risk with the score tied in a game like this.”

Cash got the ball out of his glove as fast as he could, throwing on to Mickey Stanley, who had shifted over to cover second base. In a split-second play, Stanley slapped down the tag and Brock was out, caught stealing. For one of the few times in the Series, the Tigers had stopped the Cardinals’ speed game.

Yet that single putout didn’t mean Lolich was out of the woods. But it helped when the Cardinals’ next batter, Julian Javier, lined out to Stanley. If Brock had safely reached second base on the play before, the infield would have been drawn in and the drive would likely have been a hit, probably scoring Brock. Thanks to the pick-off, the game remained scoreless.

Afterward, Curt Flood beat out an infield hit and the St. Louis running game was back in business. Even though he was often lost in Brock’s shadow, Flood also certainly had the wheels to steal a base. Like Brock before him, Flood took a long lead, waiting for Lolich to throw home. But once again the Tiger’s left-hander won the waiting game. After another beat or two, he threw over to Cash, a perfect pick-off move, and Flood was caught in no man’s land. In between bases, Flood tried to race on to second, only to be tagged out. Amazingly, Lolich had gotten out of the inning by picking off the Cardinals’ top two threats on the base paths.

The game remained scoreless with Gibson realizing he now “had to navigate one more time through the fat part of Detroit’s lineup.”

Mickey Stanley led off for Detroit in the top of the seventh inning and Gibson promptly struck him out. For a moment, it appeared it would be another easy inning for the St. Louis ace as Al Kaline then grounded out to Cardinals’ Mike Shannon for the second out. Still, often the most memorable moments begin with small, almost innocent events. So it was in the seventh.

Concerned that Norm Cash could hit one out of the ballpark, breaking up the scoreless tie, Gibson kept the ball low in the strike zone, and Cash got enough of the bat on the ball to bounce one over Javier’s head and into right field. Willie Horton followed him by grounding a single through the left side of the Cardinals’ infield.

“Gates [Brown] had been in my ear about Gibson,” recalled Horton, who was 0-for-7 against Gibson in the Series coming into the game and zero for two in this contest. “He was telling to me to get that ball in play, just put it out there and see what happens. We had to do better against Gibson than just going up there and striking out all the time.”

Years later, those two pedestrian singles would grate on Mike Shannon, the Cardinals’ third baseman that afternoon. Cash’s hit was a bad hop past Javier, while Shannon believes he could have corralled Horton’s single if he hadn’t been guarding the third-base line so closely. In any event, the Tigers had two men on, two out, with Jim Northrup stepping up to the plate. He was the last guy Gibson wanted to see in this situation. Later, Gibson said that Northrup “had given me more trouble than any other Tiger.”

With two men on, Gibson couldn’t afford to walk a batter. He needed to get ahead in the count, move the odds in his favor. Unfortunately, for the Cardinals and their hopes for a repeat championship, Northrup was thinking the same thing.

Gibson threw a fastball, looking for strike one. Northrup was ready for it and laced a solid line drive to center field. When Gibson turned to follow the flight of the ball, his first thought was that Curt Flood, his good friend and roommate, would track this one down as he had done so many times before. But Flood initially broke in a few steps before reversing direction in an attempt to catch up with Northrup’s hard liner. Later, Flood said that he initially lost sight of the ball in the background of white shirts in the stands behind home plate.

To this day, Flood’s teammates defend his play on the ball.

McCarver said the wet field caused the centerfielder to slip. “On a dry field, he gobbles that ball up,” he said.

Shannon added that Flood “didn’t misjudge” the line drive. “His first step was in,” Shannon said. “That’s what you’re supposed to do. When the ball’s hit over your head, you’ve got to come in a little to push off and go back. He slipped.”

The condition of the outfield certainly didn’t help Flood at this pivotal moment. Four afternoons before, the hometown football Cardinals had hosted the Dallas Cowboys at Busch. “Most of the football games were played in the outfield area,” grounds superintendent Barney Rogers said. “They didn’t dig up around the pitcher’s mound or home plate too much.”

To the Cardinals’ surprise, Northrup’s liner soared past the Cardinals’ center fielder and bounced against the wall for a triple. Cash and Horton came around to score. Two runs that at that point seemed to Gibson “like two thousand.” Reeling from the blow, Gibson gave up a double to Bill Freehan. When the inning ended, the defending champions trailed Lolich and the Tigers, 3–0.

Back in the Cardinals’ dugout, Flood apologized to Gibson.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “It was my fault.”

“Like hell,” Gibson told him. “It was nobody’s fault.”

Years later, Gibson added, “What is often forgotten about that play is the fact that Northrup hit the damn ball four hundred feet.”

For his part, Northrup absolutely agreed. “I hit the crap out of it,” he said years later. “Everybody wants to talk about Flood and how he should have played it. But I know I hit that fastball of Gibson’s a ton.”

Whether the play would be remembered as a miscue or a solid shot depended on whom you were rooting for. The fact was the Cardinals now trailed by three runs with only three innings left. And despite pitching on short rest, Lolich didn’t show any signs of letting St. Louis off the hook.

The great Cardinals’ teams of the 1960s were built upon pitching, defense, and speed. What they lacked was an abundance of power. Now trailing 3–0 to Detroit, the St. Louis offense desperately sought any break it could get. With one out in the bottom of the seventh, Northrup did his best to accommodate them when he booted a ball, putting Shannon on first base. The Cardinals were unable to take advantage, however, as Tim McCarver flied out and then Roger Maris popped out to shortstop.

After Gibson made quick work of the Tigers in the top of the eighth, he expected that his day would be over. Manager Red Schoendienst would look to his bench to generate some kind of attack. Indeed, Phil Gagliano pinch-hit for shortstop Dal Maxvill (who to that point in the Series had gone 0–22 and whose overall World Series batting record is a record low for a position player) to start the inning. In the on-deck circle, Gibson watched Gagliano ground out. At this point, the Cardinals’ ace expected to be called back to the dugout, with Dick Schofield or Bobby Tolan taking his turn at the plate. Yet in a surprise move, perhaps an indication of how well Lolich was pitching on this day, but also surely a nod to how effective Gibson had been in the Cardinals’ epic championship run, Schoendienst gestured for the pitcher to bat. Gibson went down swinging, taking a big cut on a Lolich fastball.