Sun in a Bottle (14 page)

Authors: Charles Seife

From fusion scientists’ point of view, this kind of fusion was worthless. Scientists were hoping to get a hot cloud of nuclei fusing with itself, a thermonuclear fusion reaction. Instead, Columbus had made a small handful of very hot nuclei interact with cooler ones. This was roughly equivalent to shooting nuclei at a stationary target, and doing that, scientists had concluded, would always consume more energy than it produced. The neutrons produced by the instability, dubbed

instability neutrons

or

false neutrons

, weren’t a sign of energy production—just the opposite. Columbus’s neutrons were the sign of energy consumption, not energy production. The false neutrons had given the Los Alamos scientists false hope. Even so, the pinch technique still seemed within striking distance of igniting fusion.

instability neutrons

or

false neutrons

, weren’t a sign of energy production—just the opposite. Columbus’s neutrons were the sign of energy consumption, not energy production. The false neutrons had given the Los Alamos scientists false hope. Even so, the pinch technique still seemed within striking distance of igniting fusion.

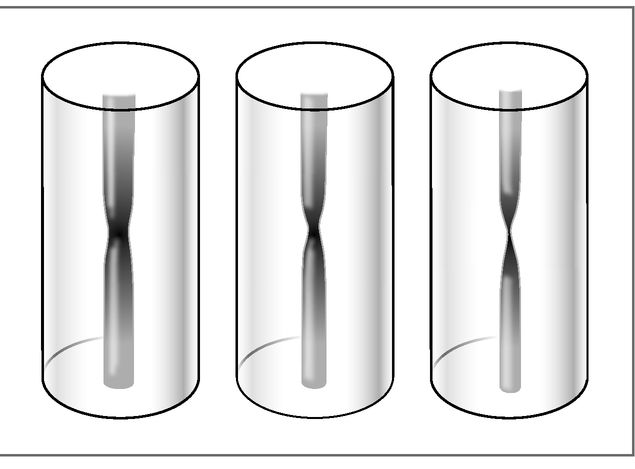

SAUSAGE INSTABILITY:

If a pinching plasma is slightly narrower in one place, that narrowing will get more and more severe and eventually squeeze the plasma to make it look like a pair of sausages.

If a pinching plasma is slightly narrower in one place, that narrowing will get more and more severe and eventually squeeze the plasma to make it look like a pair of sausages.

By this time, the Americans knew they had competition from both the Russians and the British. Project Sherwood poured increasing amounts of money into ever-larger machines of all types. The most expensive one in the Sherwood portfolio was the model-C Stellarator proposed by Spitzer, which would cost roughly $16 million to design and build. So it was a humiliation when it appeared that the British had won the fusion race with a much smaller and less-expensive machine: ZETA.

ZETA, which had cost less than $1 million to build, was a powerful pinch machine. Its name reflected the optimism of its designers; ZETA was an acronym for Zero-Energy Thermonuclear Assembly, thermonuclear because it would achieve fusion and zero-energy because it would produce as much energy as it consumed. It was a very bold claim.

ZETA began operation in mid-August 1957 at the Harwell laboratory near Oxford. It wasn’t long before the machine made a big splash. Late in the evening of August 30, the ZETA device started producing neutrons. The scientists did hasty checks to make sure there wasn’t an equipment failure of any sort; the neutrons were real. Pinch. Neutrons. Pinch. Neutrons. Like their American counterparts before them, the British physicists thought the neutrons were the signature of fusion; after all, neutrons were the smoking gun that everybody had been seeking for so long. There were a few skeptics on the ZETA team—some doubted that ZETA had actually achieved fusion—but the joyful chorus of self-congratulation drowned out the voices of doubt. The mood was jubilant. Most of the ZETA team thought they had finally done it; they had built the first, rudimentary, artificial sun. The physicists present popped open a bunch of beers to celebrate.

38

38

After weighing the evidence and crunching the numbers, the physicists at Harwell concluded that the plasma in the ZETA machine was reaching a temperature of five million degrees with every pinch, creating thermonuclear reactions and producing neutrons. If so, this was big news. It would be the first time that scientists had achieved fusion in a controlled environment. The British team naturally wanted to release their initial results right away, revealing the brilliant future of limitless energy to the public. But the Americans balked.

Earlier in the year, the British and Americans had decided to share data on fusion reactors with each other, and they were to decide jointly when and how to declassify the data and release it to the public. This last point became a source of contention. The Americans were reluctant to make an announcement about ZETA, in part because Project Sherwood had no signal achievements to brag about at the time. It looked as though the Brits had beaten the pants off the Yanks, so the Yanks needed some time to catch up. Thus, citing security issues, the United States tried to delay the announcement for a year. A second United Nations conference was scheduled for 1958, and what better place was there, U.S. officials argued, to release the results?

The British were unhappy about the American insistence on secrecy, and it is hard to keep a secret if one party wants to reveal it. Naturally, the secret didn’t stay secret for very long. By early September, news of ZETA’s success was leaking out. The English press was buzzing with rumors of successful nuclear fusion in the ZETA machine. By October, British scientists—including the Nobel laureate and Harwell lab head, John Cockcroft—hinted at encouraging results from the device. However, in deference to the Americans, nobody made an official pronouncement.

Hints about ZETA’s success got harder and harder to ignore. In November, a spokesperson for the British Atomic Energy Authority (BAEA) stated, “The indications are that fusion has been achieved” at ZETA, but gave no further details. English scientists briefed the House of Commons on their achievement. But the weeks ticked away without any description of what, exactly, had happened at Harwell.

The mystery deepened in December. Even as the BAEA denied that the United States was deliberately “gagging” ZETA scientists, preventing them from releasing their results, a BAEA spokesman admitted that Britain was awaiting American approval to publish the details of the Harwell experiment. The British press was infuriated and accused the United States of playing politics with a crucial scientific achievement, of needlessly delaying publication of an important experimental result. The British had beaten the Americans at their own game, and Lewis Strauss and the Project Sherwood crew seemed to be holding up the declassification process to give themselves time to catch up to the Brits.

39

39

To the ZETA scientists, it was more than merely frustrating. Without a publication, it was as if the experiment had never happened. In science, publication is everything; without it, an experiment is worthless. It is easy for anybody to make an outrageous scientific-sounding claim. If you use the right buzzwords, you can make it extremely convincing; you can easily make the public believe that your claim is true. That’s what happened with Ronald Richter. Given a platform by Juan Perón, Richter trumpeted a remarkable achievement—based on pseudoscience—around the globe. Important people, including Perón, believed him. But very few scientists did. That is because Richter did not publish any scientific data that would have allowed specialists to verify his claim. To a scientist, an experiment is not believable without the precise details of how it was run and what the researchers involved observed. Only when scientists reveal the inner workings of an experiment to the world can their peers scrutinize the work and confirm or refute it. Only then will they be taken seriously. By blocking the publication of the ZETA results, the Americans were denying the British their chance at scientific glory.

Finally, the Americans succumbed to the pressure and gave Britain the go-ahead to publish the ZETA findings. When the Harwell scientists announced, in mid-January, that they were publishing their results in

Nature

at the end of the month, the British press was ecstatic. When they learned that the ZETA papers were to be accompanied by papers about Project Sherwood’s pinch project, the press was absolutely livid. It looked as if Lewis Strauss and the Americans, with their expensive machines, were trying to steal some of the Harwell laboratory’s glory. “Admiral Strauss’ tactics have soured what should be an exciting announcement of scientific progress so that it has become a sordid episode of prestige politics,” blared the British Sunday

Observer

. Despite the hurt feelings, everyone was relieved that the long wait was about to end.

Nature

at the end of the month, the British press was ecstatic. When they learned that the ZETA papers were to be accompanied by papers about Project Sherwood’s pinch project, the press was absolutely livid. It looked as if Lewis Strauss and the Americans, with their expensive machines, were trying to steal some of the Harwell laboratory’s glory. “Admiral Strauss’ tactics have soured what should be an exciting announcement of scientific progress so that it has become a sordid episode of prestige politics,” blared the British Sunday

Observer

. Despite the hurt feelings, everyone was relieved that the long wait was about to end.

When the

Nature

papers finally came out on January 24, the British and American scientists held a joint press conference. John Cockcroft announced that it was “90% certain” that ZETA’s neutrons had come from fusion, and outlined a twenty-year research plan that would lead to fusion reactors. The Americans presented their results, too, but they weren’t nearly as striking as ZETA’s. The press in the United States spun the story as a great British-American achievement. “Gains in Harnessing Power of H-Bomb Reported Jointly by U.S. and Britain,” the

New York Times

declared; “Nations Called Equal—Many Questions to Be Resolved.” America’s Columbus II machine was given pride of place above Britain’s ZETA, and the newspaper emphasized that the two nations were “neck and neck.” However, the rest of the world’s press ignored the American research and celebrated Britain’s triumphant conquest of fusion energy. In England, tabloid papers blasted the news across their pages, promising “UNLIMITED POWER from SEA WATER”: no more electricity bills, no more smog, no need for coal, power that would last for a billion years. Newspapers around the globe followed suit; they were quick to trumpet the prospect of limitless energy, energy that would be at humanity’s fingertips within two decades. No longer would any nation be held hostage because of a lack of oil. Even the Soviets congratulated the British—pointedly ignoring the Americans—on their “achievement in harnessing thermonuclear energy” and expressed their “admiration.”

40

ZETA seemed to have begun a new era of humanity, the era of unlimited fusion energy, and it was the envy of the world.

Nature

papers finally came out on January 24, the British and American scientists held a joint press conference. John Cockcroft announced that it was “90% certain” that ZETA’s neutrons had come from fusion, and outlined a twenty-year research plan that would lead to fusion reactors. The Americans presented their results, too, but they weren’t nearly as striking as ZETA’s. The press in the United States spun the story as a great British-American achievement. “Gains in Harnessing Power of H-Bomb Reported Jointly by U.S. and Britain,” the

New York Times

declared; “Nations Called Equal—Many Questions to Be Resolved.” America’s Columbus II machine was given pride of place above Britain’s ZETA, and the newspaper emphasized that the two nations were “neck and neck.” However, the rest of the world’s press ignored the American research and celebrated Britain’s triumphant conquest of fusion energy. In England, tabloid papers blasted the news across their pages, promising “UNLIMITED POWER from SEA WATER”: no more electricity bills, no more smog, no need for coal, power that would last for a billion years. Newspapers around the globe followed suit; they were quick to trumpet the prospect of limitless energy, energy that would be at humanity’s fingertips within two decades. No longer would any nation be held hostage because of a lack of oil. Even the Soviets congratulated the British—pointedly ignoring the Americans—on their “achievement in harnessing thermonuclear energy” and expressed their “admiration.”

40

ZETA seemed to have begun a new era of humanity, the era of unlimited fusion energy, and it was the envy of the world.

Other nations began to emulate the British. The Swedes announced that they were building a ZETA-like device that could compete with the one at Harwell. Just two weeks after the announcement, Japanese scientists announced that they, too, had achieved thermonuclear fusion—and they were producing more neutrons than the British were. The Russians also started building a ZETA clone. But the Britons weren’t going to fall behind: by early May, they were busy upgrading ZETA and were planning a more powerful (and more expensive, at $14 million) machine, ZETA II. Its designers thought that ZETA II would heat plasmas to one hundred million degrees and produce more energy than it consumed. It would be the world’s first fusion power plant. On May 7, the

New York Times

optimistically reported on the characteristics of the new machine: “Britain Indicates Reactor Advance” read the headline. The following week, though, the paper planned a much less adulatory article: “H-Bomb Untamed, Britain Admits.” The dream had come crashing down. Once again, the culprit was those damn false neutrons.

New York Times

optimistically reported on the characteristics of the new machine: “Britain Indicates Reactor Advance” read the headline. The following week, though, the paper planned a much less adulatory article: “H-Bomb Untamed, Britain Admits.” The dream had come crashing down. Once again, the culprit was those damn false neutrons.

Even while the ZETA scientists were cracking open beers, toasting their first fusion reactions, Basil Rose, a physicist at Harwell, was consumed by skepticism. He was unconvinced that the ZETA neutrons were truly from thermonuclear fusion. While Cockcroft and others plotted their twenty-year path to fusion energy, Rose racked his brain for a way to allay his doubts. He simply had to come up with a way of proving that the neutrons were coming from fusion and not from a bizarre instability.

The method he came up with was analogous to what the Columbus scientists had done several years before: he would look at the symmetry of the system. Rose ran the ZETA machine twice, once in its normal operating mode and once with magnetic fields and currents reversed. If the neutrons were coming from a true thermonuclear reaction, the neutrons would have the same energies, no matter whether the machine was running normally or in reverse. The reaction should be symmetrical. It wasn’t. The neutrons generated by normal ZETA had energies different from those produced by reverse ZETA. The neutrons weren’t coming from thermonuclear fusion. They, too, were false neutrons.

As soon as Rose published his results in

Nature

—on June 14, a month after Britain revealed its plans for the ZETA II—it became obvious that scientists at the Harwell lab had deceived themselves. John Cockcroft immediately regretted his “90% certain” remark and assured the public that ZETA was a success even though it hadn’t achieved thermonuclear fusion. “It is doing exactly the job we expected it would do and is functioning exactly the way we hoped it would,” he sheepishly explained. However, the damage had been done.

Nature

—on June 14, a month after Britain revealed its plans for the ZETA II—it became obvious that scientists at the Harwell lab had deceived themselves. John Cockcroft immediately regretted his “90% certain” remark and assured the public that ZETA was a success even though it hadn’t achieved thermonuclear fusion. “It is doing exactly the job we expected it would do and is functioning exactly the way we hoped it would,” he sheepishly explained. However, the damage had been done.

Like Richter before them, the British had gotten burned for crying fusion. Driven by their optimism and goaded by their egotistical desire for glory, the ZETA scientists had humiliated themselves in front of the world. The stakes of fusion energy were so high—virtually unlimited power to the nation that controlled it—that scientists couldn’t resist staking an early claim in achieving that lofty goal.

ZETA was a public relations disaster. For years, the cloud of ZETA hung over fusion scientists all over the world. In America, Project Sherwood physicists, despite their relief at not losing the race to the Brits, were despondent about what had happened. Fusion scientists were beginning to realize that fusion energy would be much more difficult to harness than they had thought. Fast pinches were not enough. There was no easy road to building a power plant with a magnetic bottle.

Even as scientists learned more about fusion, the dream of unlimited power seemed to slip further away. Another contender, though, was on the horizon, another way to confine a plasma and initiate a fusion reaction that would ignite another race for fusion energy.

CHAPTER 5

HEAT AND LIGHT

Other books

The Unifying Force by James Luceno

Tales of Wonder by Jane Yolen

Wash by Margaret Wrinkle

Mirror Image Seduction (Feline Shifters of Down Under Book 1) by Tamsin Baker, Khloe Wren

My Roman Conquest by Ashley Fox

One More Day by Hadley, Auryn

Nightwitch by Ken Douglas

Beneath An Ivy Moon (Legacy Of Magick Series, Book 4) by Ellen Dugan

Peter Pan by James Matthew Barrie

The Selected Poetry of Yehuda Amichai by Chana Bloch and Stephen Mitchell