Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism (22 page)

Read Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism Online

Authors: James W. Loewen

BOOK: Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism

5.04Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Most suburbs incorporated between 1900 and 1968. Often they formed in the first place to become sundown towns. According to John Denton, who studied housing in the San Francisco Bay area, “One of the principal purposes (if not the entire purpose) of suburban incorporations is to give their populations control of the racial composition of their communities.” When they incorporated, suburbs typically drew their boundaries to exclude African American neighborhoods. In 1912, white voters in Brentwood, Maryland, rejected incorporation with tiny adjoining North Brentwood, majority black, so in 1924, North Brentwood incorporated separately. Two Texas sundown suburbs—Highland Park and University Park—are entirely surrounded by Dallas, which tried to annex them repeatedly between 1919 and 1945. The “Park Cities,” as they call themselves, repeatedly rebuffed Dallas. Under Texas law, if one municipality entirely surrounds another, the larger can absorb the smaller. Although Dallas encircles the Park Cities, it can annex neither, because on one side each borders “another” city—the other Park City. I put quotation marks around “another” because the Park Cities are alike and even form one school system.

68

68

In 1960, white city officials of Phoenix, Illinois, another south suburb of Chicago, pulled off what suburban expert Larry McClellan calls “a stunning example of racial politics.” Instead of using municipal boundaries to keep African Americans out, they redrew the city limits to create white flight without ever moving! In the 1950s, Phoenix was going black, so in 1960, its white city officials “de-annexed” the part of the city where most whites lived, ceding themselves to Harvey, the next suburb west, and leaving Phoenix to the African Americans. It didn’t work: Harvey also proceeded to go majority-black.

69

Regardless of the Creation, the Result Was the Same69

How a town went sundown—owing to a violent expulsion, a quiet ordinance, or a more subtle freeze-out or buyout—made no consistent difference over time. Either way, African Americans lost their homes and jobs, or their chance for homes and jobs. Either way, the town defined itself as sundown for many decades, and that decision had to be defended.

The white townspeople of Sheridan, Arkansas, for instance, were probably no more racist than residents of many other Arkansas towns until 1954. Indeed, they may have been

less

racist than many: as Chapter 7 tells, they almost chose to desegregate their schools in response to

Brown,

a step taken by only two towns in Arkansas. After the 1954 buyout, however, Sheridan’s notoriety grew. As a lifelong resident said in 2001, the town “developed a reputation that was perhaps more aggressive than it really deserved. For years, black people wouldn’t even stop in Sheridan for gas.” In fact, Sheridan probably deserved its new reputation. Although originally prompted by a single individual, no Sheridan resident lifted a voice to protest the forced buyout of its black community. On the contrary, two different Sheridan residents said in separate conversations in 2001, “You know, that solved the problem!” Implicitly they defined “the problem” as school desegregation, or more accurately, the existence of African American children. With a definition like that, inducing blacks to leave indeed “solved the problem.” Having accepted that “solution,” whites in Sheridan were left predisposed to further racism. According to reports, they posted signs, “Nigger, Don’t Let the Sun Set On You Here.” Long after non-sundown towns in Arkansas desegregated their schools, Sheridan fans developed a reputation for bigotry when their high school played interracial teams in athletic contests. This reputation grew in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Sheridan played rival Searcy, a majority-white town, but not a sundown town. Searcy had a talented African American on its roster, and when he got the ball in games played in Sheridan, white parents and Sheridan students would yell “Get the nigger” and similar phrases.

70

less

racist than many: as Chapter 7 tells, they almost chose to desegregate their schools in response to

Brown,

a step taken by only two towns in Arkansas. After the 1954 buyout, however, Sheridan’s notoriety grew. As a lifelong resident said in 2001, the town “developed a reputation that was perhaps more aggressive than it really deserved. For years, black people wouldn’t even stop in Sheridan for gas.” In fact, Sheridan probably deserved its new reputation. Although originally prompted by a single individual, no Sheridan resident lifted a voice to protest the forced buyout of its black community. On the contrary, two different Sheridan residents said in separate conversations in 2001, “You know, that solved the problem!” Implicitly they defined “the problem” as school desegregation, or more accurately, the existence of African American children. With a definition like that, inducing blacks to leave indeed “solved the problem.” Having accepted that “solution,” whites in Sheridan were left predisposed to further racism. According to reports, they posted signs, “Nigger, Don’t Let the Sun Set On You Here.” Long after non-sundown towns in Arkansas desegregated their schools, Sheridan fans developed a reputation for bigotry when their high school played interracial teams in athletic contests. This reputation grew in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Sheridan played rival Searcy, a majority-white town, but not a sundown town. Searcy had a talented African American on its roster, and when he got the ball in games played in Sheridan, white parents and Sheridan students would yell “Get the nigger” and similar phrases.

70

The methods blur into each other on a continuum. Towns that went all-white nonviolently frequently employed violence to stay that way. A city official in tiny De Land remembers as a child in about 1960 overhearing an adult conversation to the effect that a black family recently moved into De Land, but there was a mysterious fire in their house and they left. “De Land had a sundown rule,” the adults went on, “so what did they expect?” In this case, the passage of an ordinance probably contributed to private violence by heightening white outrage at the violation of community mores. Whether a given town became all-white violently or nonviolently, formally or informally, does not predict how it will behave later.

71

71

Because suburbs got organized later than most independent towns, after the Nadir was well under way, a much higher proportion of them were created as sundown towns from the beginning, as the next chapter shows.

5

Sundown Suburbs

No lot shall ever be sold, conveyed, leased, or rented to any person other than one of the white or Caucasian race, nor shall any lot ever be used or occupied by any person other than one of the white or Caucasian race, except such as may be serving as domestics for the owner or tenant of said lot, while said owner or tenant is residing thereon. All restrictions, except those in paragraph 8 (racial exclusion), shall terminate on January 1, 1964.—Typical restrictive covenant for property in Edina, Minnesota, sundown suburb of Minneapolis

1

A

CROSS AMERICA, most suburbs, and in some metropolitan areas almost all of them, excluded African Americans (and often Jews). This pattern of suburban exclusion became so thorough, even in the traditional South, and especially in the older metropolitan areas of the Northeast and Midwest, that Americans today express no surprise when inner cities are mostly black while suburbs are overwhelmingly white.

CROSS AMERICA, most suburbs, and in some metropolitan areas almost all of them, excluded African Americans (and often Jews). This pattern of suburban exclusion became so thorough, even in the traditional South, and especially in the older metropolitan areas of the Northeast and Midwest, that Americans today express no surprise when inner cities are mostly black while suburbs are overwhelmingly white.

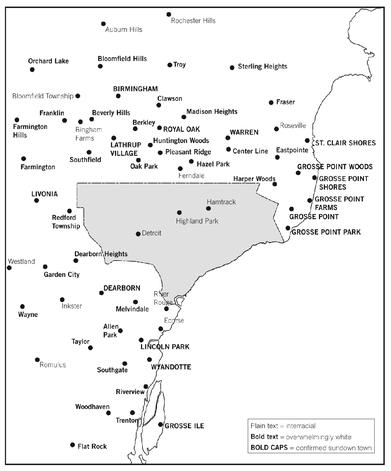

After 1900, precisely as the suburbs unfolded, African Americans were moving to northern metropolitan areas as part of the Great Retreat and, beginning around 1915, as part of the Great Migration. But the suburbs kept them out. Detroit, for example, slowly became overwhelmingly black, even though it touches at least four sundown suburbs—Dearborn, Grosse Pointe, Melvindale, and Warren. Map 4 shows these contiguous sundown suburbs and many others. Some black families from Detroit would have moved to these suburbs the way whites did, had they been allowed. Indeed, Inkster, a majority-black suburb founded in 1921, lies just beyond Dearborn, farther from Detroit. Yet while Inkster to the west and Detroit to the north and east grew in black population, Dearborn, between them, grew even whiter. Many of its residents took pride in the saying, “The sun never set on a Negro in Dearborn,” according to historians August Meier and Elliott Rudwick. Dear born’s longtime mayor Orville Hubbard, who held office from 1942 to 1978, told a reporter that “as far as he was concerned, it was against the law for Negroes to live in his suburb.” Dearborn was an extraordinary case because Hubbard was so outspoken, but David Good, Hubbard’s biographer, cautions us not to see him as unique: “In a sense, Orville Hubbard’s view was no different from that in any of a dozen or more other segregated suburbs that ringed the city of Detroit—or in hundreds of other such communities scattered across the country.”

2

2

Map 4. Detroit Suburbs

At least 47 of 59 suburbs outside Detroit were overwhelmingly white, decade after decade. Eleven were interracial and one requires more census study. I have confirmed only 15 of the 47 as sundown suburbs, but further research would surely confirm most of the rest. In 1960, for example, Garden City, which abuts interracial Inkster, had just two African Americans, both women, probably both live-in maids, among its nearly 40,000 residents. Twenty years later, large suburbs like Berkley, Clawson, Farmington, and Harper Woods had not one black inhabitant. Such numbers imply exclusion.

Moreover, of the 11 interracial suburbs, several were not meaningfully integrated; the black/white border merely happened to run through the suburb. In 1940, for example, 1,800 African Americans lived in Ecorse, but not one east of the tracks, where the whites lived. In 1970, whites in River Rouge could recall only one black family, “the first in 50 years,” that lived on the east side, and they were intimidated into leaving.

a

a

In time, suburbs came to dominate our nation. Between 1950 and 1970, the suburban population doubled from 36 million to 74 million as 83% of the nation’s population growth took place in the suburbs. By 1970, for the first time, more people lived in suburbs than in central cities or rural areas. Thirty years later, more lived in suburbs than in cities and rural areas combined. Since suburbanites vote at higher rates than anyone else, they are now by far the dominant political force in the United States. Thomas and Mary Edsall provide these statistics: during the twenty years from 1968 to 1988, the percentage of the presidential vote cast in suburbs grew from 36% to 48%. The rural vote declined from 35% to 22% while central cities stayed constant at about 29.5%. “What all this suggests,” they conclude, “is that a politics of suburban hegemony will come to characterize presidential elections.”

3

4

3

4

Not only in politics do suburbs rule. In his 1995 primer

The Suburbs,

John Palen notes the increasing influence of suburbs in economic and cultural spheres:

The Suburbs,

John Palen notes the increasing influence of suburbs in economic and cultural spheres:

Suburbs have gone from being fringe commuter areas to being the modal locations for American living and working. There has been a suburban revolution that has changed suburbs from being places on the periphery of the urban cores to being the economic and commercial centers of a new metropolitan area form. Increasingly, it is the suburbs that are central with the cities being peripheral.

As early as 1978, a

New York Times

survey of suburban New Yorkers found that more than half did not feel they belonged to the New York metropolitan area at all, and a fourth never went to the city even once in the previous year. By 1987, suburban shopping malls accounted for 54% of all sales of personal and household items. Suburbs now contain two-thirds of our office space. Palen notes that “more than ¾ of the job growth during the 1980s in America’s twenty largest metropolitan areas occurred in the suburbs.” He claims that the suburbs are also becoming dominant culturally. Many of the sporting and cultural events that used to take place downtown now play in suburban arenas and concert halls. In short, “although it somewhat twists the language, suburbs are more and more frequently the center of the metropolitan area.”

5

The Good LifeNew York Times

survey of suburban New Yorkers found that more than half did not feel they belonged to the New York metropolitan area at all, and a fourth never went to the city even once in the previous year. By 1987, suburban shopping malls accounted for 54% of all sales of personal and household items. Suburbs now contain two-thirds of our office space. Palen notes that “more than ¾ of the job growth during the 1980s in America’s twenty largest metropolitan areas occurred in the suburbs.” He claims that the suburbs are also becoming dominant culturally. Many of the sporting and cultural events that used to take place downtown now play in suburban arenas and concert halls. In short, “although it somewhat twists the language, suburbs are more and more frequently the center of the metropolitan area.”

5

Why did this happen? The American rush to the suburbs wasn’t just to avoid African Americans. Indeed, it wasn’t

primarily

to avoid African Americans. It took place in metropolitan areas with few African Americans as well as areas such as Detroit whose core cities became majority-black. Families moved to the suburbs for two principal reasons: first, it seemed the proper way to bring up children, and second, it both showed and secured social status. That is, Americans saw suburbs as the solution to two problems: having a family and having prestige. Suburban dwellers wanted to raise their children to be safe, happy, and well educated in metropolitan areas. They also wanted to be upwardly mobile and to display their upward mobility.

primarily

to avoid African Americans. It took place in metropolitan areas with few African Americans as well as areas such as Detroit whose core cities became majority-black. Families moved to the suburbs for two principal reasons: first, it seemed the proper way to bring up children, and second, it both showed and secured social status. That is, Americans saw suburbs as the solution to two problems: having a family and having prestige. Suburban dwellers wanted to raise their children to be safe, happy, and well educated in metropolitan areas. They also wanted to be upwardly mobile and to display their upward mobility.

The two functions were closely related, since “living well” begets status. As the twentieth century wore on, Americans told themselves increasingly that children need their own grass to play on and their own trees to play under, and families need their own plots of earth in which to put down roots. Today this idea is so firmly embedded in our national culture, at least that of our lower-upper and middle classes, as to seem “natural.”

6

Of course, by “natural” we really mean so deep in our culture that we do not—perhaps cannot—question it. And of course, communities that embody such “obvious” values are by definition better—hence more prestigious—places to live.

6

Of course, by “natural” we really mean so deep in our culture that we do not—perhaps cannot—question it. And of course, communities that embody such “obvious” values are by definition better—hence more prestigious—places to live.

Not all suburbs fit the same mold, of course. Some are centered around industry, such as Dearborn, Michigan, around Ford, and Granite City, Illinois, around the graniteware plant and several steel mills. Some of these working-class suburbs were founded as white enclaves; some, like Dearborn and Granite City, became sundown suburbs by forcing out their African Americans; still others remained interracial, especially if they had begun as interracial independent cities, as did Pontiac, Michigan. Among the benefits that sundown suburbs confer is participation in what political scientist Larry Peterson calls a “type of Americanization”—leaving the old Polish, Greek, or Italian city neighborhood for a new, ethnically mixed, but all-white neighborhood in the suburbs.

7

7

Other books

Suspicions: A Twist of Fate\Tears of Pride by Lisa Jackson

Iron Disciples MC 1 Joy Ride by Eliza Stout

The Complete Drive-In by Lansdale, Joe R.

Loving Jay by Renae Kaye

Love Rekindled (Love Surfaced) by Michelle Lynn

Warehouse 13: A Touch of Fever by Cox, Greg

To Kiss A Kilted Warrior by Rowan Keats

Purple Golf Cart: The Misadventures of a Lesbian Grandma by Ronni Sanlo

Maelstrom by Taylor Anderson