Surveillance or Security?: The Risks Posed by New Wiretapping Technologies (17 page)

Read Surveillance or Security?: The Risks Posed by New Wiretapping Technologies Online

Authors: Susan Landau

The next controversy was over "post-cut-through dialed digits," the

digits punched in after the call has been established by the carrier to a

switch. These might be the actual number you are dialing after reaching

your long-distance provider from a toll-free number, an extension, a bank

account number and the pass code needed to access the account, or a

prescription number to the druggist. Law enforcement agencies argued

that the post-cut-through digits were call-identifying information and

should be included in the transactional data delivered in a pen register; the telephone companies argued it could be content and should not. When

the FCC accepted the FBI's interpretation, the case went to court,103 which

remanded it to the FCC, complaining about the lack of specificity in the

FCC's ruling. The FCC determined that post-cut-through digits should be

supplied with an "appropriate legal instrument," leaving open whether

that meant a pen register for call-identifying information or a full-blown

wiretap order for content.104

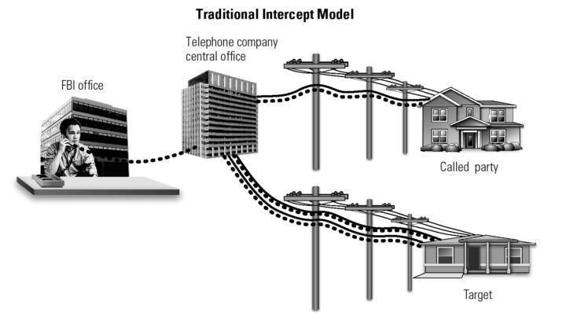

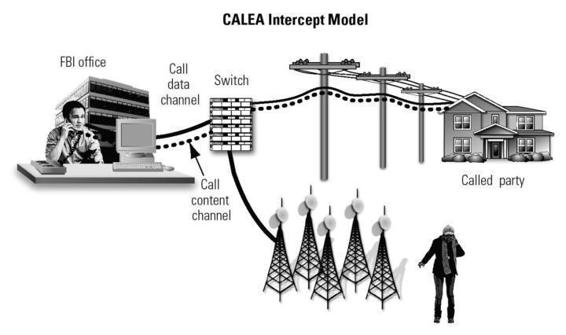

Figure 4.1

Traditional intercept versus CALEA intercept. Illustration by Nancy Snyder.

This case also included a dispute over location information. While

CALEA stated that "such call-identifying information shall not include any

information that may disclose the physical location of the subscriber

(except to the extent that the location may be determined from the telephone number),""' the FBI pressed to have the information-in the form

of the location of the closest antenna tower-included in the signaling

information associated with cell phone communications. The court agreed

to this.

As long as carriers complied with the CALEA standards, regardless of

whether they could actually execute court-ordered wiretaps, the carriers

fell under the "safe-harbor" provision of the law. But for each day that law

enforcement was unable to execute a court-authorized wiretap on a noncompliant system, the telecommunications carrier was subject to a fine of

$10,000. This was not inconsequential. Congress authorized $500 million

to cover telephone-company costs to do the upgrades to CALEA-that was

part of why the telephone companies had dropped their opposition to

CALEA in 1994. As of 2008, only 10 percent of the funds remained,106 while

nearly 40 percent of U.S. switches remained noncompliant.107

CALEA marks a radical transformation of U.S. wiretap law. Title III, FISA,

and ECPA delineated the circumstances under which a wiretap order could

be authorized. Those laws left the customer-facing telephone companies

in charge of determining how to satisfy the government's surveillance

needs. By putting a law enforcement agency into the role of developing

telephone switching standards, CALEA turned this model on its head. The

FBI had little experience with telephone design, and even less with serving

the privacy needs of the public. The process of implementing CALEA, supposed to be in place in 1998, has taken much longer.

There was also the issue of extending the law's reach. FBI Director Louis

Freeh had testified in Congress that the FBI was not seeking to include

voice communications over the Internet within the law's purview108 and

CALEA has a clear exemption for "information services.i109 In 1994

this meant the Internet.110 Neither the legislative commitments nor the

law prevented the FBI from notifying the FCC in 2003 that nascent VoIP services posed a threat to law enforcement wiretapping. The FBI asked that

the FCC extend CALEA to VoIP. In the summer of 2005, mimicking its

decision on how VoIP should handle E911, the FCC extended CALEA to

broadband Internet access providers and providers of interconnected VoIP

services, VoIP that could send and receive calls from the PSTN. In both

instances, the VoIP user is connecting to the PSTN in a fixed, predetermined location, making the location of a tap easy to manage.

To no one's surprise, industry and civil liberties groups took the issue

to court. To many people's surprise, the U.S. Court of Appeals concurred

with the FCC. The dissenting judge told his colleagues to read the law,"'

section 1002 (b)(2)(A) of which explicitly states that assistance capability

requirements "do not extend to information service providers."

Around the same time the FCC decided that VoIP providers connecting

with the public telephone network would be required to give the location

for any E911 calls.112 This was a seemingly reasonable request on its face.

In fact, IP-based networks do not automatically have such location information available, and this requirement is complex to satisfy.

Activities were proceeding on other fronts as well. In July 2000, the Wall

Street Journal reported the FBI had developed a tool with the poorly chosen

name of Carnivore for wiretapping at ISPs.13 Carnivore was a packet sniffer

designed to execute legally authorized wiretaps and pen-register orders at

ISPs. The FBI argued that Carnivore was simply a natural application of

wiretapping technology to the Internet, but the differing nature of the two

networks suggested otherwise. There was concern over privacy of the users

not targeted by the system, but nonetheless "seen" by it. Carnivore, later

renamed DCS3000, had not been built with privacy in mind.14 The ISPs

were not pleased by the FBI solution, and, in at least one case, had gone

to court over it.115

As the public and Congress raised questions about Carnivore, the

Department of Justice seemed to be backing away from the tool. In the

summer of 2001, the department agreed to a policy review of issues raised

by the packet sniffer. But then September 11 occurred. With it, everything

changed.

4.5 Wiretapping Post-September 11

The attacks of September 11, 2001, were an enormous shock to the United

States. In one way, however, the Department of Justice was very prepared;

just eight days after the planes flew into the buildings, Attorney General

John Ashcroft provided Congress with a forty-page draft antiterrorism bill.116

There were any number of mistakes made by U.S. intelligence that

allowed the events of September 11 to occur.117 Nonetheless the immediate

reaction after the events of that day was not to look at where government

institutions had failed-indeed it took over a year before the September 11

commission was established-but instead to focus on giving the government additional tools to stop such an event from recurring."' Congress

and the White House swung into action.

While initial administration and congressional efforts were bipartisan,

within two weeks the White House began pressing hard for the adoption

of its draft legislation. The discussion became partisan, and there was little

room for public discussion of civil liberties issues.119 Even focusing only on

electronic surveillance-the legislation was much broader than that-the

new law was quite expansive.

The most important change in the law was the transformation from

foreign intelligence being the "primary" purpose to simply a "significant"

purpose of the surveillance (§218). Other important interception aspects of

the USA PATRIOT Act included: §203(b), permitting law enforcement officers to share wiretap information with other federal officials if the information contains foreign intelligence or counterintelligence; §206, which

expanded FISA to roving wiretaps; §214, which weakened standards for FISA

use of pen registers and trap-and-trace devices; §216, which stated that a

pen register and trap-and-trace order applied nationally, not just in the

jurisdiction in which it was issued;12' §217, which eliminated the need for

an interception order in cases where law enforcement sought to monitor

activities of a computer trespasser.121 In addition, the law added several crimes

to the list of serious crimes for which an intercept order was warranted.

One section that was problematic was §216, which updated the law

regarding pen registers and trap-and-trace orders to ensure they applied to

the Internet. There was no definition of what "routing" and "addressing"

meant in the context of pen registers and trap-and-trace devices, 112 an

omission that the Department of Justice agreed left open the possibility

that "reasonable minds may differ as to whether, and at what stage, URL

information might be construed as content."123 There was also initial

concern that §217 might be used by law enforcement to monitor users

simply with the consent of an ISP. However, the law was written to limit

such interception to genuine trespassers and not to users of the system

(whether paid subscribers, students on a university system, etc.).124

Several sections of the law were due to expire in 2005.125 In the end, all

but one-§203(b), which was modified-were renewed. It looked as though

the United States, over a twenty-seven-year period from 1978 to 2005, had put together a robust legal regime for foreign-intelligence wiretapping.

There was, however, a loophole.

4.6 Warrantless Wiretapping

When FISA was passed in 1978, it permitted the warrantless wiretapping

of radio communications within the United States if at least one party on

the communication was outside the country-as long as the government

was not using the warrantless exemption as a way to target a known, particular U.S. person inside the United States. This exemption was intended

to be temporary, with the expectation that Congress would provide legislation for radio surveillance later.126 Congress never did. With time, the

National Security Agency (NSA), the U.S. government's eavesdropping

agency, grew to depend on this exception. And with time, the government

came to believe that the exception could grow. Fiber-optic cables were

replacing radio, and the decreasing percentage of overseas communications being sent by satellite was thwarting the warrantless exemption

present in FISA.127 The government argued for extending the old warrantless regime to a new communications technology. There was certainly a

rationale for the U.S. government's warrantless surveillance.

The fiber-optic build-out that occurred in the last two decades of the

twentieth century made the United States a communications transit point

for the entire world. As is shown in figure 4.2, connections between Europe

and Asia, between South America and Europe, and even between South

America and South America, or Asia and Asia, went through the United

States. There were any number of reasons for this geographic oddity. One

was that U.S. providers underbid overpriced regional carriers, which

explains why inter-South American traffic might travel via Miami. A

second cause was politics: sometimes communications could not travel

directly between two nations, but could go via a third party (for some time

this was the case with Taiwan and China). A third reason was technology.

The United States is home to many of the world's email servers (Yahoo

Mail, Hotmail, Gmail).'2$ Thus email between two people in Quetta and

Kabul, for example, may travel via a server in Oregon. If any of those communications had gone by satellite, the NSA would have been able to simply

pluck the signal out of the air. But modern technology meant that these

communications were arriving in the United States by fiber-optic cable and

that complicated the situation.

On December 16, 2005, the New York Times broke a story it had been

holding for a year at the government's request, namely that since shortly after the attacks of September 11, 2001, the United States had been monitoring the international communications of hundreds, if not thousands, of

people within the United States without a warrant. At any one time up to

five hundred people were being monitored. The Times reported government

claims that only international communications were targeted and no

purely domestic calls had fallen into the intelligence agency net. The government also stated that the eavesdropping uncovered a number of plots,

including that of lyman Faris, a Kashmir-born truck driver who had plotted

with Al-Qaeda to destroy the Brooklyn Bridge, and threats of fertilizer-based

bombs at British pubs and train stations.129 It was said that the program

began "on the fly" in the panic-stricken days after the attacks and initially

monitored calls between the United States and Afghanistan.13°