Tales From Moominvalley (9 page)

Read Tales From Moominvalley Online

Authors: Tove Jansson

Tags: #General, #Fantasy, #Action & Adventure, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Animals, #Juvenile Nonfiction, #Family, #Classics, #Moomins (Fictitious Characters), #Children's Stories; Swedish, #Dragons; Unicorns & Mythical, #Fantasy Fiction; Swedish, #Short Stories

The Hemulen who loved Silence

O

NCE

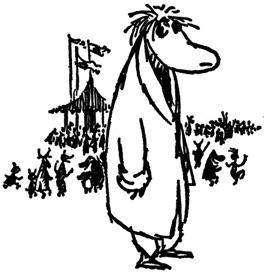

upon a time there was a hemulen who worked in a pleasure-ground, which doesn't necessarily mean having a lot of fun. The hemulen's job was to punch holes in tickets, so that people wouldn't have fun more than once, and such a job is quite enough to make anyone sad if you have to do it all your life.

The hemulen punched and punched, and while punching he used to dream of the things he would do when he got his pension at last.

In case someone doesn't know what a pension is, it means that you can do what you like in all the peace you wish for, when you're old enough. At least that was how the hemulen's relatives had explained it to him.

He had terribly many relatives, a great lot of enormous, rollicking, talkative hemulens who went about slapping each other's backs and bursting into gigantic laughs.

They were joint owners of the pleasure-ground, and in their spare time they blew the trombone or threw the

hammer, told funny stories and frightened people generally. But they did it all with the best of intentions.

The hemulen himself didn't own anything because he was on the side-line, which means only half a relative, and as he never could put his foot down about anything to anyone he always had to do the baby-sitting, to work the big bellows of the merry-go-round, and, most of the time, to punch tickets.

'You're lonely and have nothing to do,' the other hemulens used to tell him in their friendly way. 'So it might cheer you up a bit to lend a hand and be among people.'

'But I'm never lonely,' the hemulen tried to explain. 'I can't find the time to be. There's always such a lot of people who want to cheer me up. If you don't mind, I'd like so much to...'

'Splendid,' the relatives said and slapped his back. 'That's the thing. Never lonely, always on the go.'

The hemulen punched along, dreaming about a great wonderful silent loneliness, and hoped he would grow old as soon as possible.

The whirligigs whirled, the trombones trumpeted, gaffsies and whompers and mymbles shrieked in the roller coaster every night. Edward the Booble won a first prize in china smashing, and all around the sad and dreamy hemulen people danced and whooped, laughed and quarrelled and ate and drank, and by and by the hemulen grew simply afraid of noisy people who were enjoying themselves.

He used to sleep in the hemulen children's dormitory, that was bright and nice in the daytime, and at nights when the kiddies awoke and cried he comforted them with a barrel organ.

The rest of his spare time he lent a hand anywhere it was needed in a large house full of hemulens, and so he had company around the clock, and everybody was in high spirits and told him all about everything they thought and did and planned to do. Only they never gave him time to reply properly.

'Won't I grow old soon?' the hemulen once asked at dinner.

'Old? You?' his uncle shouted. 'Far from it. Buck up, buck up, nobody's older than he feels.'

'But I feel really old,' the hemulen said hopefully.

'Pish, posh,' the uncle said. 'We're going to have extra spot of fireworks tonight, and the brass band will play until sunrise.'

But the fireworks never were touched off, because that same afternoon a great rain started to fall. It continued all night and all the next day, and the next one after that, and then all the following week.

To tell the truth this rain kept up for eight weeks without a stop. No one had ever seen the like.

The pleasure-ground lost its colours, shrank and withered away like a flower. It paled and rusted, and then it slowly started to disperse, because it was built on sand.

The roller coaster railway caved in with a sigh, and the merry-go-rounds went slowly turning around in large grey pools and puddles, until they were swept off, faintly tinkling, by the new rivers that were formed by the rain.

All small kiddies, toffles and woodies and whompers and mymbles, and so forth, were standing days on end with their snouts pressed to the window-panes, looking at their July becoming drenched and their colour and music floating away.

The House of Mirrors came crashing down in millions of wet splinters, and pink drenched paper roses from the Miracle Garden went bobbing off in hundreds over the fields. Over it all rose the wailing chorus of the kiddies.

They were driving their parents to desperation, because they hadn't a single thing to do except grieve over the lost pleasure-ground.

Streamers and empty balloons were drooping from the trees, the Happy House was filled with mud, and the three-headed alligator swam off to the sea. He left two of his heads behind him, because they had been glued on.

The hemulens took it all as a splendid joke. They stood at their windows, laughing and pointing and slapping backs, and shouted:

'Look! There goes the curtain to the Arabian Nights! The dancing floor has come loose! There's five black bats from the Cave of Horror on the fillyjonk's roof! Did you ever!'

They decided in the best of spirits to start a skating rink instead, when the water froze, of course - and they tried to comfort the hemulen by promising him the ticket

punching job again as soon as they could get things going.

'No,' the hemulen suddenly said. 'No, no, no. I don't want to. I want my pension. I want to do what I feel like doing, and I want to be absolutely alone in some silent place.'

'But my dear nephew,' one of his uncles said with enormous astonishment, 'Do you mean what you say?'

'I do,' said the hemulen. 'Every word of it.'

'But why haven't you told us before?' the perplexed relatives asked him. 'We've always believed that you've enjoyed yourself.'

'I never dared tell you,' the hemulen admitted.

At this they all laughed again and thought it terribly funny that the hemulen had had to do things he disliked all his life, only because he hadn't been able to put his foot down.

'Well, now, what

do

you want to do?' his maternal aunt asked cheerfully.

'I'd like to build myself a doll's house,' the hemulen whispered. 'The most beautiful doll's house in the world, with lots and lots of rooms, and all of them silent and solemn and empty.'

Now the hemulens laughed so hard that they had to sit down. They gave each other enormous nudges and shouted: 'A doll's house! Did you hear that! He said a doll's house!' and then they laughed themselves into tears and told him:

'Little dear, by all means do exactly as you like! You can have grandma's big park, very probably it's silent as a grave nowadays. That's the very place for you to rummage

about in and play to your heart's content. Good luck to you, and hope you like it!'

'Thanks,' the hemulen said, feeling a little shrunken inwardly. 'I know you've always wished me well.'

His dream about the doll's house with the calm and beautiful rooms vanished, the hemulens had laughed it to pieces. But it really was no fault of theirs. They would have felt sincerely sorry if anyone had told them that they had spoiled something for the hemulen. And it's a risky thing to talk about one's most secret dreams a bit too early.

The hemulen went along to grandma's old park that was now his own. He had the key in his pocket.

The park had been closed and never used since grandma had set fire to her house with fireworks and moved elsewhere with all her family.