Tales From Moominvalley (12 page)

Read Tales From Moominvalley Online

Authors: Tove Jansson

Tags: #General, #Fantasy, #Action & Adventure, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Animals, #Juvenile Nonfiction, #Family, #Classics, #Moomins (Fictitious Characters), #Children's Stories; Swedish, #Dragons; Unicorns & Mythical, #Fantasy Fiction; Swedish, #Short Stories

'How unpleasant,' Moomintroll said.

'Yes, isn't it,' replied Too-ticky. 'This was the way this lady used to talk. She was ironic all day long every day, and finally the kid started to turn pale and fade around the edges, and less and less was seen of her. Last Friday one couldn't catch sight of her at all. The lady gave her away to me and said she really couldn't take care of relatives she couldn't even see.'

'And what did you do to the lady?' My asked with bulging eyes. 'Did you bash her head?'

'That's of no use with the ironic sort,' Too-ticky said. 'I took Ninny home with me, of course. And now I've brought her here for you to make her visible again.'

There was a slight pause. Only the rain was heard, rustling along over the verandah roof. Everybody stared at Too-ticky and thought for a while.

'Does she talk,' Moominpappa asked.

'No. But the lady has hung a small silver bell around her neck so that one can hear where she is.'

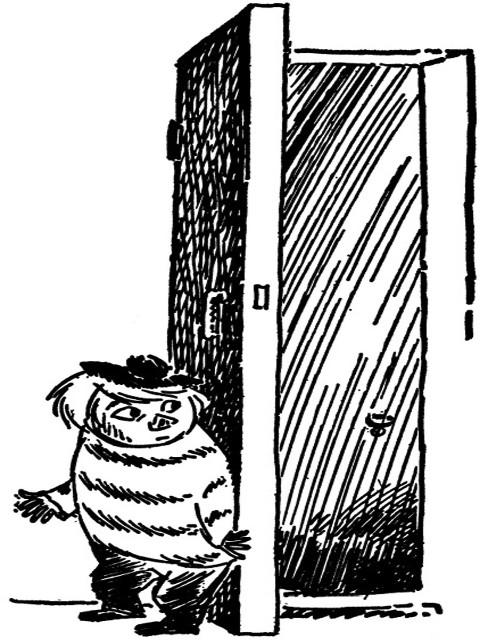

Too-ticky arose and opened the door again. 'Ninny!' she called out in the dark.

The cool smell of autumn crept in from the garden, and a square of light threw itself on the wet grass. After a while there was a slight tinkle outside, rather hesitantly. The sound came up the steps and stopped. A bit above the floor a small silver bell was seen hanging in the air on a black ribbon. Ninny seemed to have a very thin neck.

'All right,' Too-ticky said. 'Now, here's your new family. They're a bit silly at times, but rather decent, largely speaking.'

'Give the kid a chair,' Moominpappa said. 'Does she know how to pick mushrooms?'

'I really know nothing at all about Ninny,' Too-ticky said. 'I've only brought her here and told you what I know. Now I have a few other things to attend to. Please look in some day, won't you, and let me know how you get along. Cheerio.'

When Too-ticky had gone the family sat quite silent, looking at the empty chair and the silver bell. After a while one of the chanterelles slowly rose from the heap on the table. Invisible paws picked it clean from needles and earth. Then it was cut to pieces, and the pieces drifted away and laid themselves in the basin. Another mushroom sailed up from the table.

'Thrilling!' My said with awe. 'Try to give her something to eat. I'd like to know if you can see the food when she swallows it.'

'How on earth does one make her visible again,' Moominpappa said worriedly. 'Should we take her to a doctor?'

'I don't think so,' said Moominmamma. 'I believe she wants to be invisible for a while. Too-ticky said she's shy. Better leave the kid alone until something turns up.'

And so it was decided.

The eastern attic room happened to be unoccupied, so Moominmamma made Ninny a bed there. The silver bell tinkled along after her upstairs and reminded Moominmamma of the cat that once had lived with them. At the bedside she laid out the apple, the glass of juice and the three striped pieces of candy everybody in the house was given at bedtime.

Then she lighted a candle and said:

'Now have a good sleep, Ninny. Sleep as late as you can. There'll be tea for you in the morning any time you want. And if you happen to get a funny feeling or if you want anything, just come downstairs and tinkle.'

Moominmamma saw the quilt raise itself to form a very small mound. A dent appeared in the pillow. She went downstairs again to her own room and started looking through her granny's old notes about Infallible Household Remedies. Evil Eye. Melancholy. Colds. No. There didn't seem to be anything suitable. Yes, there was. Towards the end of the notebook she found a few lines written down at the time when Granny's hand was already rather shaky. 'If people start getting misty and difficult to see.' Good. Moominmamma read the recipe, which was rather complicated, and started at once to mix the medicine for little Ninny.

*

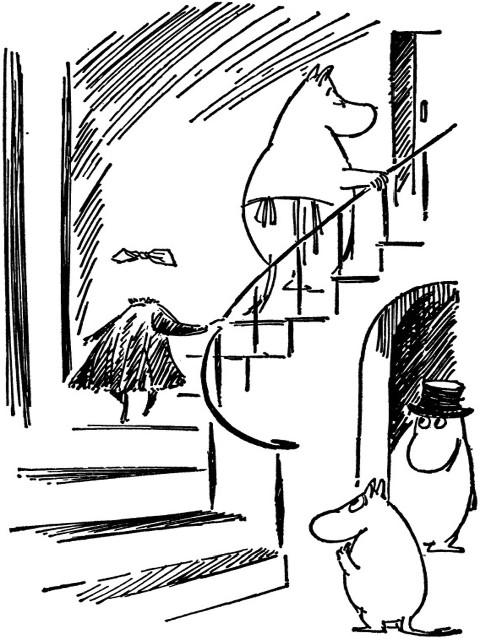

The bell came tinkling downstairs, one step at a time, with a small pause between each step. Moomintroll had waited for it all morning. But the silver bell wasn't the exciting thing. That was the paws. Ninny's paws were coming down the steps. They were very small, with anxiously bunched toes. Nothing else of Ninny was visible. It was very odd.

Moomintroll drew back behind the porcelain stove and stared bewitchedly at the paws that passed him on their way to the verandah. Now she served herself some tea. The cup was raised in the air and sank back again. She ate some bread and butter and marmalade. Then the cup and saucer drifted away to the kitchen, were washed and put away in the closet. You see, Ninny was a very orderly little child.

Moomintroll rushed out in the garden and shouted: 'Mamma! She's got paws! You can see her paws!'

I thought as much, Moominmamma was thinking where she sat high in the apple tree. Granny knew a thing or two. Now when the medicine starts to work we'll be on the right way.

'Splendid,' said Moominpappa. 'And better still when she shows her snout one day. It makes me feel sad to talk with people who are invisible. And who never answer me.'

'Hush, dear,' Moominmamma said warningly. Ninny's paws were standing in the grass among the fallen apples.

'Hello Ninny,' shouted My. 'You've slept like a hog. When are you going to show your snout? You must look a fright if you've wanted to be invisible.'

'Shut up,' Moomintroll whispered, 'she'll be hurt.' He went running up to Ninny and said:

'Never mind My. She's hardboiled. You're really safe here among us. Don't even think about that horrid lady. She can't come here and take you away...'

In a moment Ninny's paws had faded away and become nearly indistinguishable from the grass.

'Darling, you're an ass,' said Moominmamma. 'You can't go about reminding the kid about those things. Now pick apples and don't talk rubbish.'

They all picked apples.

After a while Ninny's paws became clearer again and climbed one of the trees.

It was a beautiful autumn morning. The shadows made one's snout a little chilly but the sunshine felt nearly like summer. Everything was wet from the night's rain, and all colours were strong and clear. When all the apples were picked or shaken down Moominpappa carried the biggest apple mincer out in the garden, and they started making apple-cheese.

Moomintroll turned the handle, Moominmamma fed the mincer with apples and Moominpappa carried the filled jars to the verandah. Little My sat in a tree singing the Big Apple Song.

Suddenly there was a crash.

On the garden path appeared a large heap of apple-cheese, all prickly with glass splinters. Beside the heap one could see Ninny's paws, rapidly fading away.

'Oh,' said Moominmamma. 'That was the jar we use to give to the bumble-bees. Now we needn't carry it down to the field. And Granny always said that if you want the earth to grow something for you, then you have to give it a present in the autumn.'

Ninny's paws appeared back again, and above them a pair of spindly legs came to view. Above the legs one could see the faint outline of a brown dress hem.

'I can see her legs!' cried Moomintroll.

'Congrats,' said little My, looking down out of her tree. 'Not bad. But the Groke knows why you must wear snuff-brown.'

Moominmamma nodded to herself and sent a thought to her Granny and the medicine.

Ninny padded along after them all day. They became used to the tinkle and no longer thought Ninny very remarkable.

By evening they had nearly forgotten about her. But when everybody was in bed Moominmamma took out a rose-pink shawl of hers and made it into a little dress. When it was ready she carried it upstairs to the eastern attic room and cautiously laid it out on a chair. Then she made a broad hair ribbon out of the material left over.

Moominmamma was enjoying herself tremendously. It was exactly like sewing doll's clothes again. And the funny thing was that one didn't know if the doll had yellow or black hair.

*

The following day Ninny had her dress on. She was visible up to her neck, and when she came down to morning tea she bobbed and piped:

'Thank you all ever so much.'

The family felt very embarrassed, and no one found anything to say. Also it was hard to know where to look when one talked to Ninny. Of course one tried to look a bit above the bell where Ninny was supposed to have her eyes. But then very easily one found oneself staring at some of the visible things further down instead, and it gave one an impolite feeling.

Moominpappa cleared his throat. 'We're happy to see,' he started, 'that we see more of Ninny today. The more we see the happier we are...'

My gave a laugh and banged the table with her spoon. 'Fine that you've started talking,' she said. 'Hope you have anything to say. Do you know any good games?'

'No,' Ninny piped. 'But I've heard about games.'

Moomintroll was delighted. He decided to teach Ninny all the games he knew.

After coffee all three of them went down to the river to play. Only Ninny turned out to be quite impossible. She bobbed and nodded and very seriously replied, quite, and how funny, and of course, but it was clear to all that she played only from politeness and not to have fun.

'Run, run, can't you!' My cried. 'Or can't you even jump?'

Ninny's thin legs dutifully ran and jumped. Then she stood still again with arms dangling. The empty dress neck over the bell was looking strangely helpless.

'D'you think anybody likes that?' My cried. 'Haven't you any life in you? D'you want a biff on the nose?'

'Rather not,' Ninny piped humbly.

'She can't play,' mumbled Moomintroll.

'She can't get angry,' little My said. 'That's what's wrong with her. Listen, you,' My continued and went

close to Ninny with a menacing look. 'You'll never have a face of your own until you've learned to fight. Believe me.'

'Yes, of course,' Ninny replied, cautiously backing away.

*

There was no further turn for the better.

At last they stopped trying to teach Ninny to play. She didn't like funny stories either. She never laughed at the right places. She never laughed at all, in fact. This had a depressing effect on the person who told the story. And she was left alone to herself.

Days went by, and Ninny was still without a face.