Tamar (45 page)

Authors: Mal Peet

I sat there in that unlived-in living room and understood that my dad had been insane. I wondered if he still was. I couldn’t imagine how he could have kept all that stuff dammed up inside him all this time without being at least three parts crazy.

He said, “It turned out to be much harder to disappear than I’d imagined. The practical problems are enormous, actually. After a couple of months, I was living pretty much hand to mouth. Then I had a stroke of luck. I was working in a pub down by the ferry terminal, and I got talking to a man who was waiting to meet some clients off a delayed boat. It turned out to be Colin, the guy who owns this place. One thing led to another, and he offered me a job. I’d been here almost a month before I found out that it was a stone’s throw from the head of the Tamar. It seemed such a beautiful coincidence. Or predestination, if you believe in that sort of thing.”

I didn’t know what I believed. I didn’t know if it was possible to believe in anything anymore.

I said, “I’m sorry, Dad. I can’t get my head round all this. I mean, why didn’t you just get in touch with us? Didn’t you want to? Didn’t you realize we were all off our heads with worry?”

“I couldn’t get in touch. How could I, without explaining why I’d gone? And that was the one thing I couldn’t do.”

“So what were you going to do? Stay here forever?”

“I don’t know. I suppose I was waiting for Hyde, Lubbers, Dart, whoever he is — was — to die.”

Hyde, Lubbers, Dart, whoever he was. Grandad.

“He is dead,” I said, very cold.

The word sat there between us like a toad. Dad didn’t meet my eyes. He poured more wine.

Yoyo said, “Jan, you say he came here. This is something I don’t understand. How did he find you?”

“I didn’t ask. It wasn’t that kind of . . . conversation.”

“What did he say?” I said. “What did he want?”

“Forgiveness.” Dad’s voice was so bitter. “Forgiveness. Can you imagine?”

I could. Very easily. And I thought Dad, of all people, ought to be able to.

Yoyo said, “Sorry, but I am a bit confused. You are saying that he knew you had found out these things about him?”

Dad didn’t answer for a second or two, and he didn’t look up at us.

“Yeah. I wrote to him. Not what you’d call a letter. A few words, several of them obscene. This was a couple of days after I got off the train in Plymouth. I’d been drinking. I was pretty dark, I suppose. I called him Lubbers, and a few other things besides. So yes, he knew.” He took a long drag on his cigarette. “I suppose that’s how he tracked me down. The Plymouth postmark on the letter. He’d have started from there, and . . . I don’t know. He’s a clever bastard.

Was

a clever bastard.”

I thought, He came up the river. I must have said it aloud, because Dad looked at me. “What?”

I shook my head. “It doesn’t matter. I want to know what he said. What did he say?”

“He admitted everything. Said he’d spent the rest of his life horrified by what he’d done, said it was like having cancer. I actually think he expected me to feel sorry for him. Christ! Then he started talking about love. How he’d always loved Mum, always loved me, loved you. Love, love, love. I wanted to strangle him. It was . . . appalling. Vile. And just so bloody untrue. You know how cold he was. He wouldn’t know what love was if it hit him in the face.”

I was tearful again and hated myself for it. I wiped my eyes on my sleeve, hard. “You’re wrong, Dad. I know you are. He did love Gran. I know because when she started going . . . getting ill, it broke his heart. I saw it. I was there, and you weren’t. He was so . . .”

“Guilty.”

“What?”

“Guilty. That’s the word you’re looking for. That’s what he meant by love. He’d spent the rest of his miserable life feeling guilty. Why do you think he killed himself?”

“No, Dad. No. It wasn’t like that. I know it wasn’t. And Gran loved him.”

“Did she?” There was a sneer in the question.

“Yes.

Yes

. I mean, she married him, didn’t she? And stayed with him.”

“Look, Tamar. It’s not hard to figure that out, is it? She didn’t know what he’d done. She believed he’d rescued her, saved her life, even, getting her out of Holland. She thought he was her lover’s best friend. They got to England, where she knew nobody. Didn’t even speak the language. She was pregnant. She depended on him, and he exploited that. Dependence can look like love, in a certain light.”

I got up. “I’m going for a walk,” I said. Yoyo looked at me. “By myself,” I said.

I went through into the kitchen and stopped to put on the sweatshirt I’d left there when we came in. I heard Yoyo say, “Jan, I must ask you this. Do you feel some pity at all for this man?”

And Dad said, “No, Johannes. I hope he rots in hell.”

I went back to the living-room doorway and said, “Remind me again, Dad — who was it who asked you to name me after your father?”

Then I walked out into what was left of the daylight.

I went a little way up the drive and then climbed the slope that rose away from Dad’s cottage. When I got to the top I could see the main house, a rambling white-faced building with lights on in several windows. Wisps of music. The big lawn had been mown in very precise light and darker green stripes: my father’s work, I supposed. The sunset was perfect. Soft streamers of peach-coloured cloud hung in a blue-washed sky above distant indigo hills. It all looked no more real than flimsy scenery for a school play.

Below me, off to the right, light glittered on water. I headed that way and came to an ornamental garden with, at its centre, a large pond. A weeping willow leaned over the water, its trailing branches touching their own reflections. The air was rich with the scent of jasmine. I heard voices speaking a strange language, a series of fast, broken sounds. Two men were squatting on their heels at the edge of the pond, one of them pointing at something I couldn’t see. When they stood up, I saw that they were Japanese, slim men in pale short-sleeved shirts. They stood silently for a time, then one looked at his watch and spoke. They turned and walked away along a path towards the school. Where the path emerged from the garden, a white marble statue stood on a pedestal: a naked goddess with an arm raised as if beckoning to the upstairs windows. As they passed her, one of the men reached up and patted her backside. When their laughter had faded, I went down to the pond.

Much of it was in deep shade, but where the last light fell on the water, it looked like golden oil. At first I couldn’t see what the Japanese men had been looking at. Then the willow whispered, and the same breath of wind brought the little boat out of the shadow. It was smaller than the palm of my hand and woven, like basketwork, from long slender leaves. The mast was a peeled twig, the sail a small blank sheet of paper. It carried a fragile cargo of jasmine blossom, and it drifted towards me, tilting but not toppling, trailing black ripples through the gold.

It’s time to put all this stuff away. The creased English maps, a tatty fragment of silk, a photo of two young men who might have been brothers, a still unfinished crossword puzzle: the surviving items from Grandad’s box. Yes, I still think of him as that, call him that. It’s as real as any of his other names. The one thing that’s missing — apart from the money, of course — is Christiaan Boogart’s fake identity. I let Dad keep that. Whether it eases or feeds his bitterness, I couldn’t really say.

The past is a dark house, and we have only torches with dying batteries. It’s probably best not to spend too much time in there in case the rotten floor gives way beneath our feet, like it did for Dad. Like it nearly did for me.

Yoyo said to me recently, “Love and pain, that’s what families are, and they fit together like this” — he slotted the tips of our fingers together — “like cogs.” Then he smiled and put a hand on my swollen belly. “And what makes these cogs turn is hope, of course.”

“Or ignorance,” I said.

He thought about it. “Yes, or ignorance. But hope is more reliable.”

The sun has left our street now, but the late day is still warm. Through the open window I can hear, faintly, the guides’ commentaries from the tourist boats gliding along the Prinsengracht. They’ll have left the Anne Frank House behind them, and now the passengers will be aiming their cameras at the giant gaudy crown perched on the spire of the Westerkerk. Soon Yoyo will be home, and because it’s my birthday we’ll go out for something to eat. We’ll probably end up at the usual place. It’s just ten minutes away, and I can’t walk much farther than that now that the Lump has got so heavy. That’s what he calls it. It’s what he’ll say as soon as he’s come in and kissed me: “How is the Lump today?”

We’ve still not decided what to call it if it’s a boy. If it’s a girl — and for some reason I’m sure it is — she’ll be Marijke. That’s something we agreed on from the start.

NOTES AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In part,

Tamar

is a historical novel, a mix of fact and fiction. Real events gave me the bones of the story, but I’ve taken liberties with them. For example, it is true that SS Lieutenant General Hanns Albin Rauter was ambushed on a country road on the night of 6th March 1945, but not by a group of men led by Koop de Vries; they exist only in the pages of this book. Likewise, you’ll not find Mendlo or Sanctuary Farm on any real map.

I gathered the facts and assembled the skeleton of the story from a number of sources. Four books were especially helpful:

The Hunger Winter: Occupied Holland, 1944–45

by Henri A. van der Zee;

The SOE in the Low Countries

by M. R. D. Foot;

Secret Warfare

by Pierre Lorain; and

Between Silk and Cyanide: A Codemaker’s War, 1941–1945

by Leo Marks. I based the account of Rauter’s shooting and its terrible aftermath on an article by Karel Margry in volume 56 of

After the Battle

.

I am extremely grateful to the kind (and bilingual) staff of the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation in Amsterdam; they even allowed me to work there when it was supposed to be closed.

I have an enormous and now unrepayable debt to Paul Peters, whose account of his experiences as an SOE wireless operator in occupied Holland urged me to write this novel. Not long before he died, I sat with him and his wife, Marijke, in their garden in Laren, Holland, and we discussed such merry topics as handguns, hunger, amphetamine dependence, suitcase transceivers, code silks, and suicide pills, Marijke, shared her still-vivid memories of being a teenage “hunger tripper.” At one point I asked Paul what it had felt like, being “underground,” living in dread of raids and Nazi detector cars. It was a stupid question, I suppose, but he considered it carefully (like a squirrel looking for the best way into a nut) and eventually said, “Boring.” It was the most interesting use of the word I’d ever heard, and it gave me my way into the story.

My editor at Walker Books is Averil Whitehouse. For her creativity, diligence, and patience, no expression of thanks could be adequate. After working with me, it’s a miracle that she’s not trapping clouds with her feet or chatting to invisible angels.

Finally, an apology, if you happen to be Dutch. I’ve used the terms

Holland

and

the Netherlands

as though they mean the same thing. That’s wrong, but it’s what we British do, and I couldn’t find a convenient place in the story to explain the difference.

Mal Peet

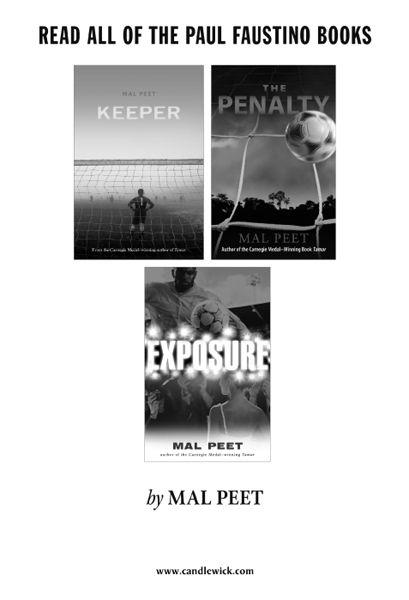

is the author of several books for young adults, including

Keeper,

an American Library Association Best Book for Young Adults. About

Tamar,

he says, “I belong to a generation whose fathers were soldiers, sailors, or airmen during the Second World War. Some of these men were willing to talk about their experiences; some were not. My own father wasn’t. (Or perhaps I didn’t want to listen.) A friend of mine had a father whose wartime experiences were actually secret. He worked underground for the British secret services in Nazi-occupied Holland. He still had his silks, the sheets of code used for his radio transmissions. These scraps of fabric were my starting point for

Tamar

. It’s a story about secrets, lies, false identities, and coded messages. It’s also, I hope, a plea for forgiveness.” Mal Peet lives in Devon, England.