Ten Pound Pom (19 page)

Authors: Niall Griffiths

The plane leaves Australian airspace and the pains leave the mother’s legs. As if they’re umbilically linked to Australia; they stretch as the plane moves away from the country and eventually snap and are twanged back to Oz earth like severed hamstrings.

An age later they land in London and get on a train to Liverpool. The parents give each other a look as the train starts to slow at Edge Hill along trash-strewn railway tracks beneath a sky the colour of drain-water. On the platform at Lime Street, the mother’s mother is there to greet them, wearing a headscarf and mac and holding a plastic bag. The father’s face falls further.

And they grow and age and change. It is discovered that Nicola has a serious heart defect – due, maybe, to the

travel-sickness

pills which the mother took on the trek across the

Nullarbor – which needs to be treated with a big and invasive operation. She is in hospital for a long time, and the boy weeps when he sees her; tiny, octopus’d by tubes. But the operation is successful. The father discovers an off-licence on Myrtle Parade, close to the hospital, that sells his favourite Swan lager. The boy, in later years, will use this off-licence when staying with his girlfriend on Bedford Street South and when all goods in the shop are protected by smash-proof perspex and it is run by the most hilariously rude man the boy, or the young man he will then be, has ever met.

Jump to 2000. Nicola, a woman now, is working in Liverpool Museum. She is approached by a couple who ask her if she remembers them. They are Lily and Jerry. They last saw Nickie when she was an infant, and it is truly incredible that they recognise her now.

Five years or so later, there’s an unexpected knock at the mother’s and father’s door. The dad opens it. There’s Peter Higgins on the doorstep, Higgy, soon to become the Mighty Hig.

Soon after that, Nickie and her husband return to Australia, and New Zealand, for a long holiday. Shortly after that, Tony does the same thing with his second wife, soon to become his second ex. And shortly after that, I too go back. And, of course, return.

They grow, and age, and change.

The plane takes off at 11 a.m. I’m in the air for twelve hours and I land in Los Angeles at 7 a.m. the same morning. Hate long-hauls. I don’t understand them. Some hours to kill in LA

so I get a cabbie to drive me around and show me some sights and I’m unimpressed and then I board the plane to Vancouver and I’m utterly exhausted and the world swims and spins and Vancouver customs take over two hours to clear, the interrogation at the desk taking half an hour itself, and another cabbie drives me into a city of sparkling towers surrounded by huge and snow-veiled mountains and at a traffic light the driver of the next car has a tattoo on his arm which reads ‘FILIPINO THRU N FUCKIN THRU’ and I check into my hotel, the Quality Hotel at 1335 Howe Street, and sleep for a few hours then I go exploring and drinking and in the morning my pockets are filled with beermats and cigarette papers with various names and numbers scrawled on them by the lovely citizens of this lovely city which Dylan Thomas called ‘a handsome hellhole’ and which I grow to think of, affectionately you understand, as ‘a stunning shitpit’. I’m in it for five days. I drink a lot and walk a lot in a kind of relaxed rush and slowly feel a very heavy weight lift off my shoulders and I gradually realise how glad I am to be out of Australia. It was getting to me, that country, and I don’t realise how much so until I wake up on my second day in Vancouver and breathe a deep sigh of relief. I spend a lot of time gazing at the mountains and the inland sea. I explore Gastown and, again, narrowly miss a mugging on Hastings and Main. Glittering bigness of the city. Even the beggars are sweet: ‘Good morning sir, and excuse me, but can I be a pain in the ass and trouble you for fifty cents?’ I’ve been in Canada before, in Ottawa, and was a tad underwhelmed then, but Vancouver I love. I could stay here longer. It’s not Australia.

I have a bulkhead seat back to London next to a sweet German girl, only eighteen, who’d just had a holiday in

Vancouver on her own, and we land ten hours later and I’m exhausted and the plane to Manchester is delayed three hours and then when I’m on it it sits on the tarmac for a further two and the flight itself takes twenty mere minutes and I think of asking the steward to ask the pilot if he can empty the

shit-tanks

over Old Trafford but don’t and we land and I can hardly walk I’m so tired but there’s my girlfriend who I haven’t seen for seven weeks and we have a rib-cracking hug and my luggage has been lost but I’m past caring. We drive back to my parents’ house and I go in and the first thing I say to them is: ‘Thank

Christ

you brought us back from Oz’. And that’s it.

But the weight of a long history is a good one to carry. I dwell on this as we drive back, the next day, to Wales. The castles, the hill-forts, the old houses, the standing stones and cairns on the mountain tops and in the green fields. A depth of human life is open and available here, at your shoulder, ready to hand, and there’s a heft to it but it’s a good weight to carry, like muscle or a favourite coat. Makes you feel part of a grand and epic story. And the seasons turn around you, here, come and come again, alternately turning your skin pink then brown, pink then brown. Measure your life in the appearance and disappearance of swallows.

At home, there’s a parcel waiting for me; a copy of

Diary of a Welsh Swagman.

I’d tracked it down on-line in an internet caff in Vancouver. Thirty quid. I’d forgotten I’d ordered it. My eyelids are closing as if made of iron and it’s all I can do to stay upright and my words are slurred and I don’t feel good so I’ll start reading it tomorrow, when I feel better.

I'm sure it's obvious from the text who I wish to thank by name, but further thanks must go to Tony, Higgy, Uncle Roy, my mum and dad, and Ian Peddie. Also to the many Aussies I know and love in that country and this, not least among them Pete Salmon and Kerry Watson of The Hurst.

Niall Griffiths was born in Liverpool in 1966 and now lives and works in Aberystwyth.

His novels are:

Grits

(2000), a tale of addicts and drifters in rural Wales;

Sheepshagger

(2001), the story of Ianto, a feral mountain boy;

Kelly

+

Victor

(2002),

Stump

(2003), which won two Book of the Year awards;

Wreckage

(2004) and

Runt

(2006). There is also a work for younger readers,

Bring it Back Home

; a book in a series of Mabinogion re-tellings,

The Dreams of Max and Ronnie

; and two works of non-fiction,

Real Aberystwyth

and

Real Liverpool

.

Niall Griffiths also writes travel pieces, restaurant and book reviews, and radio plays.

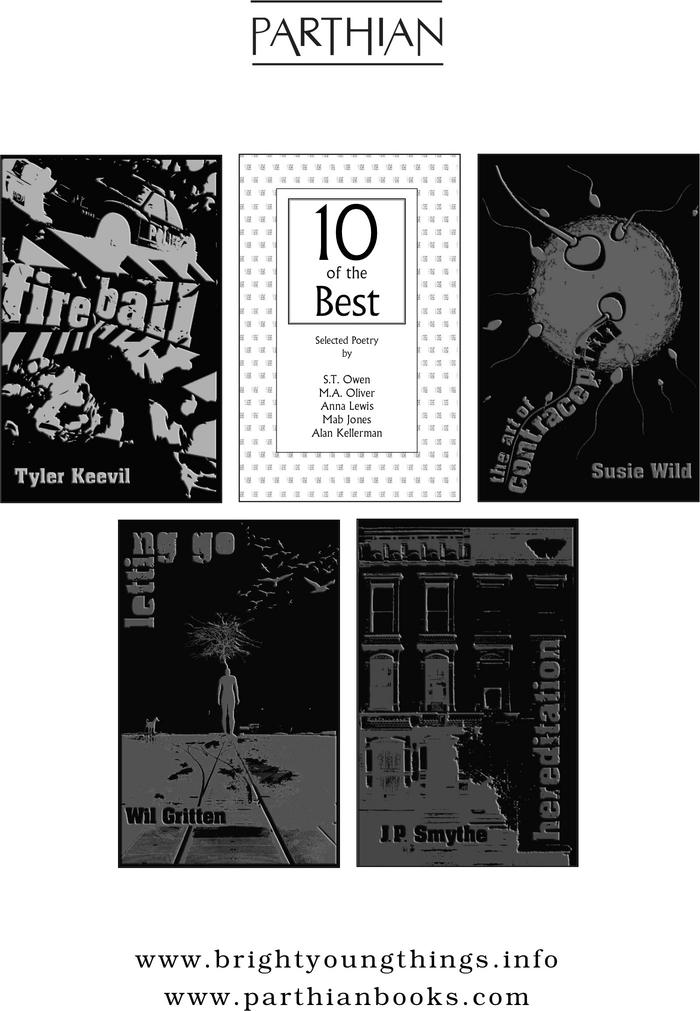

First published in 2011

by Parthian

The Old Surgery

Napier Street

Cardigan

SA43 1ED

www.parthianbooks.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

The publisher acknowledges the financial support of the Welsh Books Council.

All rights reserved

© Niall Griffiths 2011

The right of Niall Griffiths to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Editor: Lucy Llewellyn

Cover illustration by Chris Iliff

Cover design by www.theundercard.co.uk

Typesetting by Lucy Llewellyn

ISBN 9781908069542

If you enjoyed this book, please visit

www.parthianbooks.com

for information on our other publications.