The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less (36 page)

Read The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less Online

Authors: Richard Koch

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Psychology, #Self Help, #Business, #Philosophy

•

The sustainability concern.

If the 80/20 Principle leads to a huge focus on what works today, isn’t there a danger that it won’t work tomorrow? This concern is equally applicable in business and in our broader lives.

•

The balance concern.

As Chow Ching says, the concern is that we can’t focus just on the “best” parts of life, because without the rest of life the best would no longer be the best. Balance doesn’t matter in business, because the way the economy advances is through the battle of highly specialized—and therefore unbalanced—firms. But balance may be essential for human happiness.

TWO DIFFERENT DIMENSIONS OF THE PRINCIPLE

What I have realized from your feedback is that there are really two quite distinct—in some ways even opposite—dimensions or uses of the 80/20 Principle.

On the one hand, there is the

efficiency

dimension. This is where we want to achieve things in the fastest possible way with the least possible effort. Typically this domain involves things that are not hugely significant to us, except as a means to an end. For example, if we look on our work as mainly a means to earn money, because we want to do other things with other people outside of work—and it is these latter things that really matter to us—then work falls squarely into the box marked “efficiency.” We want to use the 80/20 Principle to get our work done as productively and quickly as possible, and get on with our real life. So the 20 percent approach is the way we should use the principle. We focus on the most productive 20 percent, perhaps doubling our time on those matters, and, as far as possible cut out everything that is not in the high-efficiency 20 percent box. In terms of the illustration I gave in Chapter 10 on “Time Revolution,” we should perhaps spend two days on the high-efficiency 20 percent, and then devote the rest of the week to what we really care about. Simplistically, we can expect to increase the value of our work to 160 percent of what it was before (we get two lots of 80 percent, each derived from one day of work, the 20 percent). Where possible, we also reduce our working week to two days.

The efficiency dimension can also be applied to matters outside work that are not really important to us, those that are chores. Into this 20 percent box fall, for example, all the people we have to meet socially but don’t really want to, all the obligations we don’t want but can’t get rid of, doing our taxes, cleaning the garage, doing the gardening if we don’t enjoy it and can’t slough it off onto someone who does, and so forth. The objective is to find the 20 percent that is most important and that gives us 80 percent of the results, and get it out of the way as rapidly and painlessly as we can.

On the other hand, there is the

life-enhancing

dimension of the 80/20 Principle. What belongs in this box is anything that is truly important to our lives, whether it is work, our personal relationships, what we wish to achieve, the hobby that gives us immense pleasure, or anything else that fulfills us and will give us consolation on our deathbed. When we look back on our life to date, and look forward to our life to come, and enjoy our life as it is in the current moment, anything that gives us a warm glow and makes us feel glad to be alive—all of that falls into the life-enhancing box. What the great American industrial psychologist Abraham Maslow labelled “hygiene factors”—food, shelter, material needs—are important when they are not met, but relatively unimportant once they have been satisfied. The hygiene factors, in my terms, fall into the efficiency box and require a 20 percent solution, the most productive solution with the least expenditure of life energy.

The 80/20 Principle is an essential part of realizing and enhancing what we could call the poetry of life, for two reasons. First, the principle can help us confront what is really important in our lives. Who are the few people, what are the few things, which really make our life worthwhile? Unless we are really poor or sad, these are not the instrumental aspects of life, the means to an end, like money, acclaim, important jobs, or status of any kind. These come and they go. They are outward forms, they do not touch our hearts or souls, they do not define who we are. Provided we have food and shelter, what really matters is loving and being loved, self-expression, personal achievement

and

relaxation, the ability to think and create, the chance to connect with nature and other people—above all, enhancing the lives of the friends and family we truly care about.

Second, the principle clears away space for these fantastic facets of life. By doing the non-essential things more briskly and economically, with as little absorption of our life energy as we can contrive, we capture time, territory, and tranquillity for the essential parts of life. Instead of having what matters crammed into the margins and corners of our life, we can put what’s essential where it belongs, center stage, at the heart of our being.

When it comes to the essential parts of life, the 20 percent or less that defines our uniqueness and individual destiny, we should devote our energy and our very soul to such matters, without stinting on time, money, or any other means to that end. Efficiency requires the 20 percent approach. But what is life-enhancing deserves a 200, 2,000, or 2,000,000 percent approach. There is no limit to the amount of effort or time that is appropriate for what enhances—or even defines—our lives.

So to answer the three concerns:

•

Corner cutting.

It’s only within the efficiency segment of our lives that we should aim to cut corners and do things lazily and fast. For anything life enhancing, we take the longest, deepest, or highest possible route.

•

Sustainability.

A sensible use of the principle requires a long-term view, and an awareness of potential unintended consequences if we assume that the current position with regard to effort and reward will not change. For example, 10 percent of customers may currently give us (say) 80 percent of profits. But maybe, if a new competitor focuses on our super-profitable customers, our profits won’t last. Moreover, hidden away within the 90 percent of marginal or unprofitable customers may be a fast-growth company that could, if carefully cultivated, end up being a new winning account. In the fishing example, too great a focus on the super-abundant waters, without building in some restraints to allow the fish to reproduce, leads to disaster.

In the broader areas of life, too, our focus on what enhances our life needs to be long-term and intelligent. Skills and relationships require investment. We should be selective about which abilities and friends really matter, and then take time and extraordinarily patient effort to build the foundations of a lifetime commitment. No corner cutting here, and equally no instant gratification! It’s a mistake to work for the sake of work or to amass riches by doing something we hate. But it’s very wise to make a huge commitment to developing skills and relationships that make our lives different, enjoyable, and worthwhile.

•

Balance.

Should we be balanced or unbalanced? Both. We should be unbalanced on the efficiency stuff, on everything that is not critical to our place in the world. And in a way, we should be unbalanced on the life-enhancing matters too, carefully targeting the few activities and relationships that have the greatest value and potential value for us. But within the life-enhancing domain we need a balance of work and leisure, of self-directed and shared projects, of time for ourselves and time for others, of enjoyment of current enthusiasms and investment to build the future. We can find our yin and yang within the life-enhancing sector. Were it otherwise, we would never find people who enjoy their work and their play, who are happy because wherever they are, they love what they do and they do what they love.

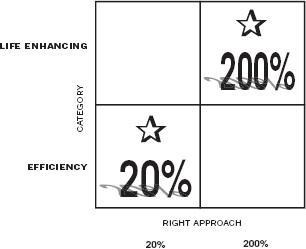

Figure 40 Allocation of our time and energy relative to today

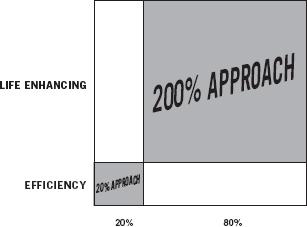

Figure 41 New allocation of time and energy (as percentage of new total)

Figure 40 shows the two dimensions of the principle and the right approach for each.

Once we have made the right decision for parts of our life that fall into each box, we can draw the matrix in a way that reflects the relative proportions. In Figure 41, the efficiency elements have been squashed up so that they only consume 20 percent of our time and energy. The 20 percent of life-enhancing areas of life are freed up to take 80 percent of our life.

Work can fall into either the efficient or the life-enhancing category. Almost certainly, you have some work that falls into each. The trick is to do progressively less of the former and more of the latter, until you reach the happy state where work really is more fun than fun.

Life outside work, too, almost certainly falls into both categories. The answer is the same. Spend less and less time and vitality on the efficiency box, and more and more on the life-enhancing box.

It’s worth asking yourself, if you could spend your time and vigor on what counts most for you, what would be the division of work and play? And how would the two relate? Most people who’ve answered this question for me say they’d spend roughly equal time on “work” and “non-work,” although “work” is self-defined and not necessarily paid work. Those who have embraced the principle find that the line between work and non-work becomes increasingly blurred.

In this sense, the yin and yang of life are re-established. Although there are two apparently opposite dimensions to the 80/20 Principle—efficiency and life enhancement—the dimensions are entirely complementary and interwoven. The efficiency dimension allows us room for the life-enhancing dimension. The common thread is knowing what gives us the results we want, and knowing what matters. Always, both for efficiency and life enhancement, the answer is a small part of the total. Always, we progress through subtraction and focus. Equally, however, 80/20 is a sterile philosophy if it just leads to efficiency. There is no point in becoming more efficient or wealthier unless there is some other goal in our mind, the goal of the soul. Those who would put 80/20 firmly back into its traditional work box are missing the point.

Let me give an example from my own life. Every day, when I am living in London or in southern Spain, I take an hour or two to cycle. This is definitely a life-enhancing activity for me: it is wonderful exercise, I travel through great scenery (Richmond Park with its deer, or mountain views in Spain) and I let my thoughts hang out as I ride and often come up with fresh ideas as a result. But it is not effortless. I reckon that 10 percent of the route in Richmond Park and 15 percent in Spain is seriously uphill; no doubt taking my heart rate up to the highest levels on the route and constituting more than 80 percent of the exercise benefit! I’m not a fanatical cyclist and I don’t really like hills—I’m glad when I can sail down the other side. But I wouldn’t choose a flat route instead. The hills, though in some ways unpleasant, add to the grandeur of the setting and provide me with “yin” activity to leaven the “yang” of riding flat or downhill.

I can tell you from personal experience and the testimony of hundreds of readers that it is possible to reverse the proportions of life, from mainly meaningless or stressful activity (yin) to mainly life enhancing (yang). Of course, we don’t want to repeat the same honeymoon or the same holiday over and over. We find fresh ways to relax. Nor do most of us want to relax most of the time. We want to exercise, to deploy and develop our skills, to think, to test ourselves, to help other people, to explore relationships of all kinds. We don’t want to be obsessed with efficiency, but we do want to dispose of the non-life-enhancing activities as easily and swiftly as possible.