The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less (16 page)

Read The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less Online

Authors: Richard Koch

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Psychology, #Self Help, #Business, #Philosophy

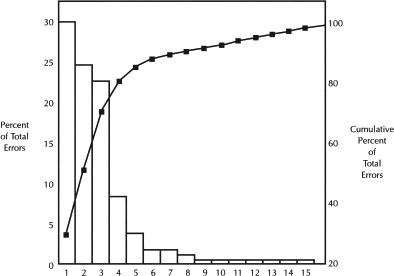

Figure 32 Causes of publisher’s typesetting overruns

Figure 33 converts this information to an 80/20 Chart. To construct this, make the causes bars in descending order of importance, put the number of causes per bar on the left-hand vertical axis and put the cumulative percentage of causes on the right-hand vertical axis. This is easily done and the visual summary of the data is quite powerful.

Figure 33 80/20 Chart of causes of publisher’s typesetting overruns

We can see from Figure 33 that three of the fifteen problems (exactly 20 percent) cause nearly 80 percent of the overruns. The cumulative line flattens out quickly after the first five causes, telling you that you are reaching the “trivial many” causes.

The major three causes all relate to authors. The publishing house could solve this problem by writing into authors’ contracts a clause making them liable for any extra typesetting costs caused by their being late or making too many corrections. A minor change like this would eliminate over 80 percent of the problem.

Sometimes it is more useful to draw an 80/20 Chart on the basis of the financial impact of the problem (or opportunity) rather than the number of causes. The method is exactly the same.

Compare performance

The 80/20 Principle states that there always are a few high-productivity areas and many low-productivity ones. All of the most effective cost-reduction techniques of the past 30 years have used this insight (often with conscious acknowledgment to the 80/20 Principle) to compare performance. The onus is placed on the majority of laggards to improve performance to the level of the best (sometimes taking the 90th percentile, sometimes the 75th, usually within this range) or else to retire gracefully from the field.

This is not the place to give chapter and verse on cost-reduction/value-improvement techniques such as benchmarking, best demonstrated practice, or reengineering. All of these are systematic expansions of the 80/20 Principle, and all, if (a big if) pursued relentlessly, can raise value to customers by tremendous amounts. Too often, however, these techniques become the latest, evanescent management fad or self-contained programs. They stand a much greater chance of success if placed within the context of the very simple 80/20 Principle that should drive all radical action:

• a minority of business activity is useful

• value delivered to customers is rarely measured and always unequal

• great leaps forward require measurement and comparison of the value delivered to customers and what they will pay for it.

CONCLUSION: SIMPLICITY POWER

Because business is wasteful, and because complexity and waste feed on each other, a simple business will always be better than a complex business. Because scale is normally valuable, for any given level of complexity, it is better to have a larger business. The large and simple business is the best.

The way to create something great is to create something simple. Anyone who is serious about delivering better value to customers can easily do so, by reducing complexity. Any large business is stuffed full of passengers—unprofitable products, processes, suppliers, customers, and, heaviest of all, managers. The passengers obstruct the evolution of commerce. Progress requires simplicity, and simplicity requires ruthlessness. This helps to explain why simple is as rare as it is beautiful.

6

HOOKING THE RIGHT CUSTOMERS

Those who analyze the reasons for their success know the 80/20 rule applies. Eighty percent of their growth, profitability and satisfaction comes from 20 percent of the clients. At a minimum, firms should identify the top 20 percent to get a clear picture of desirable prospects for future growth.

V

IN

M

ANAKTALA

1

The 80/20 Principle is essential for doing the right kind of selling and marketing and for relating this to any organization’s overall strategy, including the whole process of producing and delivering goods and services. We will show how to use the 80/20 Principle in this way. But first, we have an obligation to clear away a lot of pseudo-intellectual undergrowth about industrialization and marketing. For example, it is often said that we live in a postindustrial world, that firms should not be production led, that they should be marketing led and customer centered. These are, at best, half-truths. A short historical excursion is necessary to explain why.

In the beginning, most firms concentrated on their markets—their important customers—with little or no thought. Marketing as a separate function or activity was not necessary, yet the small business made sure that it looked after its customers.

Then came the Industrial Revolution, which created big business, specialization (Adam Smith’s pin factory), and eventually the production line. The natural tendency of big business was to subordinate customer needs to the exigencies of low-cost mass production. Henry Ford famously said that customers could have his Model T in “any color as long as it’s black.” Until the late 1950s, big business everywhere was overwhelmingly production led.

It is easy for the sophisticated marketeer or businessperson today to sneer at the primitiveness of the production-led approach. In fact the Fordist approach was plainly the right one for its time; the mission to simplify goods and lower their cost, while making them more attractive, is the foundation for today’s wealthy consumer society. Products from the low-cost factory progressively made goods in higher and higher categories available (or, in the ghastly phrase, “affordable”) to consumers previously excluded from the market. The creation of a mass market also created spending power that had not previously existed, leading to a virtuous circle of lower-cost production, higher consumption, greater employment, higher purchasing power, greater unit volumes, lower unit costs, higher consumption,…and so on in a progressive, if not unbroken, upward spiral.

Viewed in this light, Henry Ford was not a production-driven troglodite: he was a creative genius who did signal service to ordinary citizens. In 1909, he said that his mission was to “democratize the automobile.” At the time, the goal was laughable: only rich people had cars. But, of course, the mass-produced Model T, provided at a fraction of the cost of earlier cars, set the ball rolling. For good and ill, and on the whole much more good than ill, we enjoy the “horn of plenty”

2

provided by the Fordist world.

Mass industrialization and innovation did not stop with automobiles. Many products, from refrigerators to the Sony Walkman or the CD-Rom, could not have been commissioned as a result of market research. Nobody in the nineteenth century would have wanted frozen food, because there were no freezers to keep it in. All the great breakthroughs from the invention of fire and the wheel onward have been triumphs of production which then created their own markets. And it is nonsense to say that we live in a postindustrial world. Services are now being industrialized in the same way that physical products were in the so-called industrial era. Retailing, agriculture, flower production, language, entertainment, teaching, cleaning, hotel provision, and even the art of restauranteering—all these used to be exclusively the province of individual service providers, nonindustrializable and nonexportable. Now all these areas are being rapidly industrialized and in some cases globalized.

3

The 1960s rediscovered marketing and the 1990s rediscovered customers

The success of the production-driven approach, with the focus on making the product, expanding production, and driving down costs, eventually highlighted the approach’s own deficiencies. In the early 1960s, business school professors like Theodore Levitt told managers to be marketing led. His legendary

Harvard Business Review

article in 1960 called “Marketing myopia” encouraged industry to be “customer satisfying” rather than “goods producing.” The new gospel was electric. Business people fell over themselves to win the hearts and minds of customers; a relatively new branch of business studies, market research, was vastly expanded in order to discover which new products customers wanted. Marketing became the hot topic at business schools and marketing executives ousted those from production backgrounds as the new generation of CEOs. The mass market was dead; product and customer segmentation became the watchwords of the wise. More recently, in the 1980s and 1990s, customer satisfaction, customer centeredness, customer delight, and customer obsession have become the stated goals of most enlightened and successful corporations.

The customer-led approach is both right and dangerous

It is absolutely right to be marketing led and customer centered. But it can also have dangerous and potentially lethal side effects. If the product range is extended into too many new areas, or if the obsession with customers leads to recruiting more and more marginal consumers, unit costs will rise and returns fall. With additional product range, overhead costs rise sharply, as a result of the cost of complexity. Factory costs are now so low that they comprise only a small part of firms’ value added—typically less than 10 percent of a product’s selling price. The vast majority of firms’ costs lie outside the factory. These costs can be penal if the product range is too large.

Similarly, chasing too many customers can escalate marketing and selling costs, lead to higher logistical costs, and very often, most dangerously of all, permanently lower prevailing selling prices, not just for the new customers, for the old ones too.

The 80/20 Principle is essential here. It can provide a synthesis of the production-led and marketing-led approaches, so that you concentrate only on profitable marketing and profitable customer centeredness (as opposed to the unprofitable customer centeredness very evident today).

THE 80/20 MARKETING GOSPEL

The markets and customers on which any firm should be centered must be the right ones, typically a small minority of those that the company currently owns. The conventional wisdom on being marketing led and customer centered is typically only 20 percent correct.

There are three golden rules:

• Marketing, and the whole firm, should focus on providing a stunning product and service in 20 percent of the existing product line—that small part generating 80 percent of fully costed profits.

• Marketing, and the whole firm, should devote extraordinary endeavor toward delighting, keeping forever, and expanding the sales to the 20 percent of customers who provide 80 percent of the firm’s sales and/or profits.

• There is no real conflict between production and marketing. You will only be successful in marketing if what you are marketing is different and, for your target customers, either unobtainable elsewhere, or provided by you in a product/service/ price package that is much better value than is obtainable elsewhere. These conditions are unlikely to apply in more than 20 percent of your current product line; and you are likely to obtain more than 80 percent of your true profits from this 20 percent. And if these conditions apply in almost none of your product lines, your only hope is to innovate. At this stage, the creative marketeer must become product led. All innovation is necessarily product led. You cannot innovate without a new product or service.

Be marketing led in the few right product/market segments

Products accounting for 20 percent of your revenues are likely to comprise 80 percent of your profits, once you take into account all the costs, including overheads, associated with each product. It is even more likely that 20 percent of your products account for 80 percent of your profits. Bill Roatch, the cosmetics buyer for Raley’s, a retailer in Sacramento, California, comments:

Eighty percent of your profit comes from 20% of the products. The question [for a retailer] is, how much of the 80% can you afford to eliminate [without the risk of losing stature in cosmetics]…Ask the cosmetics franchisers and they say it’ll hurt. Ask the retailers and they’ll say you can cut some.

4

The logical thing to do is to expand the area devoted to the 20 percent of most profitable and best-selling lipsticks and to delist some of the slowest-selling products. Major promotion can then be undertaken in-store on the most profitable 20 percent, in cooperation with the suppliers of these top products. Note that there are always apparently good reasons trotted out as to why you need the unprofitable 80 percent of products, in this case the fear of “losing stature” by having a smaller product line. Excuses like this rest on the strange view that shoppers like to see a lot of products they have no intention of buying, which distracts attention from the product they like to buy. Whenever this has been put to the test, the answer in 99 percent of cases is that delisting marginal products boosts profits while not harming customer perceptions one iota.