The a to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers (39 page)

Read The a to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers Online

Authors: Harold Schechter

Tags: #True Crime, #General

Thierry Paulin, “The Monster of Montmartre”

Heinrich Pommerencke, “The Beast of the Black Forest”

Dennis Rader, “BTK”

Richard Ramirez, “The Night Stalker”

Melvin Rees, “The Sex Beast”

Vicytor Szczepinski, “The Doorbell Killer”

Peter Sutcliffe, “The Yorkshire Ripper”

Coral Eugene Watts, “The Sunday Morning Slasher”

Thomas Harris acknowledges this tradition in his bestselling thrillers,

Red Dragon

and

The Silence of the Lambs,

whose

FBI

heroes are on the hunt for two terrifying figures: a serial killer nicknamed the “Tooth Fairy” (because he bites his victims with a special set of dentures) and another dubbed “Buffalo Bill” (because he “always skins his humps”).

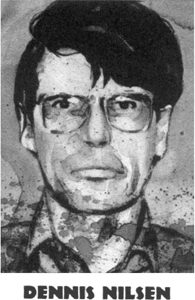

Dennis Nilsen

Dennis Nilsen; from

True Crime Trading Cards Series Two: Serial Killers and Mass Murderers;

art by Jon Bright

(Courtesy of Jon Bright and Valarie Jones)

Nilsen—the “British Jeffrey

Dahmer

,”

responsible for the grisly murders of fifteen young men—never fit the standard profile of a serial killer. As a child, he recoiled from cruelty to animals. Even bird hunting seemed wrong to him. In his adult life, he devoted himself to helping the downtrodden in his work for the Manpower Services Commission. Even his murders were motivated less by psychopathic rage than by a grotesque form of love. In the phrase of writer Brian Masters, Nilsen “killed for company.”

From early adolescence onward, Nilsen’s sexuality was marked by a necrophiliac strain. As a teenager, he liked to stretch out in front of a mirror and masturbate while imagining that the body reflected in the glass was a corpse. During a brief homosexual affair in 1972, he took home movies of

his lover—an eighteen-year-old army private—while the young man pretended to be dead.

During his eleven-year stint in the military, Nilsen worked for a time as a butcher (an occupation that provided him with skills he would later put to appalling use). After leaving the army in 1972, he joined the London police, lasting just a year. Before long, he had begun his civil service career at a government-run Job Centre. For a time, he had a contented relationship with another young man, but when it finally broke up, the reclusive Nilsen was plunged into a despairing loneliness. He reverted to bizarre autoerotic rituals. Applying powder and paint to his naked body—to make it look like the corpse of a gunshot victim—he would masturbate while regarding his own ghastly flesh in a mirror.

A few days after Christmas, 1978, Nilsen began to kill. After picking up a teenage boy in a pub, Nilsen brought him back to his apartment in the Cricklewood section of London. Frantic for companionship, Nilsen did not want the young man to leave. While the teenager slept, Nilsen garroted him with a necktie, then finished the job by submerging the boy’s head in a bucketful of water. Afterward, Nilsen stripped the corpse, gave it a tender, ritual bath, and laid it out on his bed. He kept it around the flat for the next few days, caressing it, cleaning it, masturbating over it. Eventually, he stashed it under the floorboards.

Over the next three years, the same ghastly pattern repeated itself another eleven times in Nilsen’s Cricklewood apartment. The accumulating bodies posed a problem, which Nilsen dealt with in increasingly sickening ways. At first, he stored the corpses in and around his flat—in his cupboard or under the floorboards or in a garden shed. Eventually, however, he was compelled to dismember the decaying bodies and incinerate them in a backyard bonfire. He tossed an old tire onto the blaze, hoping that the smell of burning rubber would disguise the stench of burning flesh.

In 1981, Nilsen moved to a different apartment, where he murdered three more young men and got rid of the bodies by chopping them up and flushing the chunks down the toilet. (To remove the flesh from the skulls, he boiled the heads in a big soup pot.) Eventually, this method of

Disposal

led to his downfall. When the toilets in the entire building became clogged up, neighbors called a plumber, who discovered human bones and gobs of decomposed flesh blocking the pipes.

Inside his fetid flat, police found a ghastly assortment of human

remains—heads and limbs, torsos, bones, and viscera. Nilsen, who confessed freely to fifteen murders, was sentenced to life imprisonment at his 1983 trial.

“I wished I could stop but I could not. I had no other thrill or happiness.”

D

ENNIS

N

ILSEN

N

OMADS

Here’s a sobering statistic: nearly three-quarters of all known serial killers in the world—74 percent to be exact—come from the United States (as opposed to a measly 19 percent for all of Europe). Clearly, there is something about American culture that is conducive to serial murder. Theories range from our puritanical attitudes about matters of the flesh—which presumably produce all kinds of sexual pathology—to our steady diet of media violence.

Whatever other factors are involved, one aspect of our cultural life surely exacerbates the problem: the extreme mobility of Americans. Ever since the time of the early pioneers, we’ve been a people on the go. While this cultural characteristic has undoubtedly been a source of strength (our unique freedom of movement has helped our nation develop at an extraordinary pace), it has also contributed to our notoriously high crime rate. From the days of John Wesley Hardin and Billy the Kid, highly mobile outlaws have been able to get away with murder for years by staying a few steps ahead of the law.

As early as the 1920s, however, a new and even more frightening phenomenon appeared on the criminal scene: the nomadic killer who exploited modern modes of transportation (primarily cars and trains) to keep constantly on the move, leaving behind a trail of corpses (and little else in the way of traceable clues). Earl Leonard

Nelson

—the “Gorilla Man” who strangled

nearly two dozen women during an eighteen-month, coast-to-coast killing spree—was one of the first of this deadly breed. Another was Carl

Panzram

, the globe-trotting sociopath who bragged of having committed more than one thousand homosexual rapes and twenty-one murders in the course of his extraordinarily hard-bitten life. Twenty years later, a homicidal drifter named Jake Bird racked up an even higher body count during his career of peripatetic

Axe Murder

.

It wasn’t until the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, that Americans began to perceive nomadic serial murder as a growing public menace, thanks largely to the crimes of monsters like Ted

Bundy

(who committed his lust killings in four different states) and—even more unnervingly—Henry Lee

Lucas

, who may have slaughtered as many as one hundred people during his life of aimless travel. In our mobile, fast-paced society, such itinerant psychopaths can go on killing for years, depositing corpses in quiet stretches of woods, along deserted coastlines, and beside isolated highways—preying on hitchhikers, roadside hookers, casual pickups, and other easy victims as rootless (and often as difficult to trace) as the killers themselves.

For a contrast to the nomadic style of serial murder, see

Homebodies

.

N

URSERY

R

HYMES

As everyone knows, little children are fascinated by violence and horror (if you want to read something

really

scary, check out

The Complete Grimm’s Fairy Tales).

So it’s not surprising that homicidal maniacs frequently pop up in children’s verse.

An anonymous

Axe Murderer

is the subject of this cheerfully grisly nursery rhyme:

Here comes a candle to light you to bed.

Here comes a chopper to chop off your head.

A different “chopper”—the one belonging to the infamous German lust murderer and cannibal, Fritz

Haarmann

—

features in this German nursery rhyme:

Just you wait ’til it’s your time,

Haarmann will come after you,

With his chopper, oh so fine,

He’ll make mincemeat out of you.

The bloody deeds of other real-life killers have also been celebrated in nursery rhymes. Everyone, of course, knows the one about Fall River’s most notorious daughter:

Lizzie Borden took an axe

And gave her mother forty whacks.

And when she saw what she had done,

She gave her father forty-one.

Lizzie’s near contemporary, the British “Queen Poisoner,” Mary Ann Cotton (see

Black Widows

), was also immortalized in a kiddie rhyme:

Mary Ann Cotton

She’s dead and she’s rotten.

She lies in her bed

With her eyes wide oppen.