The a to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers (40 page)

Read The a to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers Online

Authors: Harold Schechter

Tags: #True Crime, #General

The English, in fact, seem to specialize in turning lurid crimes into nursery rhymes. Two of the most notorious murderers in British criminal history were the nineteenth-century miscreants Thomas Burke and William Hare. Up until 1832, British law forbade the dissection of human corpses, except for those of executed murderers. As a result, there was a serious shortage of medical school cadavers. To fill this scientific need, some physicians turned to professional body snatchers, who would plunder fresh graves and peddle the bodies. Burke and Hare added a new twist to the body-peddling business by murdering lodgers in the boardinghouse they ran, then selling the corpses to an Edinburgh surgeon named Robert Knox. Their story has been retold many times and in various forms, from street ballads to Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Body Snatcher” (made into a 1945 Boris Karloff movie). It also inspired this little rhyme:

Burke’s the murderer, Hare’s the thief,

And Knox the boy who buys the beef.

And, of course, there’s this whimsical couplet about the legendary “Butcher of Whitechapel”:

Jack the Ripper

stole a kipper,

Hid it in his fathers slipper.

More recent British murderers have also served as the subject for children’s verse. In the mid-1950s, a physician named Buck Ruxton murdered his wife, Isabella, and a witness to the crime, his housemaid, Mary Rogerson. Then he dismembered both corpses and dumped the remains in a ravine near Moffat, Scotland. Before long, British schoolchildren were chanting this little ditty:

Red stains on the carpet, red stains on your knife.

Oh Dr. Buck Ruxton, you murdered your wife.

The nursemaid she saw you, and threatened to tell.

Oh Dr. Buck Ruxton, you killed her as well.

Today, of course, we live in less poetic times. Instead of verse, horrific crimes tend to be transformed into grisly jokes. Still, every now and then some humble versifier will compose a tribute to a serial killer. The atrocities of Edward

Gein

, for example, inspired not only a spate of sick riddles (see

Jokes

) but also these immortal lines:

There once was a man named Ed

Who wouldn’t take a woman to bed.

When he wanted to diddle,

He cut out the middle,

And hung the rest in a shed.

N

URSES

It’s bad enough when a law student (like Ted

Bundy

) or a policeman (like G. J. Schaefer, the Florida “Sex Beast” linked to twenty sadistic murders) turns out to be a serial killer. It seems even worse when the psycho is affiliated

with the healing arts—someone who has pledged his or her professional life to the care of other human beings. Deadly

Doctors

fall into this category. So do lethal nurses—those homicidal health-care workers who prey on the sick and the helpless, administering not succor and comfort but suffering and death.

In Cincinnati during the 1930s, a German immigrant named Anna Marie Hahn made a reputation for herself as a kindly, devout nurse, an angel of mercy who looked after sickly old men—all of whom happened to have very healthy bank accounts. In one way or another, Hahn managed to get her hands on their money, either by asking for “loans,” getting herself written into their wills, or stealing it outright. Then she dispatched her patients with a dose of lethal medication. Over five years, she poisoned at least eleven of the trusting old souls. She became the first woman ever electrocuted in Ohio.

While Hahn was in it strictly for the money, other lethal nurses have been motivated by even darker impulses. The notorious turn-of-the-century multi-murderer Jane

Toppan

declared that her deepest desire was to become the most prolific killer of her day. Though Toppan was accused of eleven murders, she claimed to have committed thirty-one, and some crime buffs believe that the real total was closer to one hundred. If so, then Toppan certainly achieved her ambition.

Much more recently, in the late 1980s, a sociopathic nursing-home aide named Gwendolyn Graham and her lesbian lover, Catherine Wood, devised a demented game. They decided to smother six elderly patients, selecting victims whose last initials, when strung together, spelled out the word

murder.

As it happened, the “game” became too complicated to complete, but Graham and Wood kept killing old people anyway, largely because it provided the two depraved lovers with such a powerful sexual thrill.

Not all lethal nurses are women. Richard Angelo—Long Island’s “Angel of Death”—had perhaps the weirdest rationale of all for multiple medical murder. Obsessed with the need to be recognized as a hero, the one-time Eagle Scout and volunteer fireman got his degree as a registered nurse, then went to work in the intensive-care unit of Good Samaritan Hospital, where (aptly enough) he worked the graveyard shift. Before long, postoperative patients began dropping like flies. Eventually, the authorities discovered the cause of the mysterious deaths. Between mid-September and late October

1987, Angelo had injected an average of two patients per week with Pavulon and Anectine, drugs that induced paralysis and heart failure. His reason? So that he could rush to their rescue and prove that he was a hero. Unfortunately, his plan had its flaws: out of the nearly forty patients he injected, at least ten—perhaps as many as twenty-five—died.

Beginning in 1987, another malevolent male nurse, Charles Cullen, embarked on a killing spree that would outdo Richard Angelo’s. Working in nursing homes and hospitals throughout New Jersey and Pennsylvania, Cullen dispatched as many as forty people by injecting them with various medications, such as the heart drug digoxin. When arrested in 2003, he insisted that he was simply helping to put old, terminally ill patients out of their misery—a claim seriously undercut by the fact that his victims included a twenty-one-year-old college student recovering nicely after surgery.

Dubbed “the worst serial killer in New Jersey history,” Cullen avoided the death penalty by agreeing to help prosecutors identify his victims. At his sentencing hearing in March 2006, he was denounced as “Satan’s son.” “Maybe some days he actually believes he was an angel of mercy,” said the daughter of one of his elderly victims. “Let us correct that. He is a demon from the lowest depths of hell.” He was sentenced to eleven consecutive life terms.

O

RCHARDS

Back in the early 1800s (according to legend) a wandering folk hero named Johnny Appleseed roamed across the land, turning empty fields into fertile orchards. Of course, fertility isn’t the only quality connected with apple orchards. Ever since the days of Adam and Eve, the apple tree has also symbolized sin and corruption. In real life as in myth, orchards have been associated with both goodness and crime—not only with the delicious fruits of God’s earth but also with the deadly fruits of man’s evil.

In the spring of 1873, the citizens of Labette County, Kansas, were concerned about the alarming number of travelers who had vanished while passing through the region. A posse investigating the recently abandoned farmstead of a family named Bender noticed something peculiar about the apple orchard behind the house. Depressions in the soil between the blossoming seedlings were rectangular in shape—and approximately the size of human graves. By the time the posse finished digging up the orchard, they had uncovered the bodies of a dozen people. Most of them were men, their skulls crushed with a sledgehammer. One was a baby girl who had been buried alive with her father’s corpse. As it turned out, the “Bloody Benders”

had been preying on unwary travelers for years, having turned their ramshackle farmhouse into a kind of hotel-from-hell where overnight guests rarely survived to see the light of day (see

Clans

).

An apple orchard also featured prominently in the most sensational crime of the 1920s, the Hall-Mills murder case. On a September morning in 1922, a young couple out for a stroll in New Brunswick, New Jersey, stumbled upon two corpses, male and female, lying side by side in a crabapple orchard. The woman’s throat had been slashed so ferociously that she was nearly decapitated. She had also been shot three times in the face at point-blank range. Though the dead man had not been subjected to the same mutilations, he had been killed with chilling deliberation—executed with a single bullet to the brain. What made the murders especially lurid was the identity of the victims: the Reverend Edward Wheeler Hall, pastor of New Brunswick’s most fashionable Episcopal church, and his choir-girl mistress, Mrs. Eleanor Mills. The subsequent trial of the reverend’s betrayed wife and her two eccentric brothers was the O. J. Simpson affair of its day—a frenzied, three-ring media circus followed with prurient fascination by the whole country. (As in the O.J. case, the defendants were acquitted and the case remains officially unsolved.)

The orchard where the bodies had been found turned into a major tourist attraction, where vendors hawked soft drinks and popcorn to the curious hordes, who stripped every leaf and crabapple from the branches as morbid souvenirs.

Fifty years later, orchards of another kind—the peach orchards surrounding Yuba City, California—became the site of one of the most gruesome discoveries in American criminal history. In May 1971 a farmer discovered a hacked-up corpse buried between two fruit trees. Other discoveries in nearby orchards soon followed. One by one, the corpses of migrant workers and male transients were unearthed until the body count reached a staggering twenty-five. All of the victims had been savagely slashed with a knife and a machete, and a number of them bore the signs of sexual assault. Evidence eventually led police to someone very familiar with the orchards of Yuba City, a farm labor contractor named Juan Corona, whose conviction on twenty-five counts of murder in 1973 marked him as the nation’s most prolific serial killer. Unfortunately for America, that record has since been eclipsed several times.

O

RGANIZED

/D

ISORGANIZED

See

Profiling

.

O

VENS

Few fairy tales are more chilling to children than “Hänsel and Gretel”—the story of a cannibal witch who plans to feast on two fattened children but ends up incinerated in her own oven. Perhaps that’s what adds a special dimension of horror to serial killers who use ovens to dispose of their victims. The whole situation seems like something from a childhood horror story—a real-life, exceedingly grim fairy tale.

Henri Landru, the “Bluebeard of Paris,” even

looked

like a fairy-tale villain, with his bald head, bristling brows, and spiky red beard. In spite of his unprepossessing appearance, however, he became infamous as one of the world’s leading lady-killers, marrying and murdering no fewer than ten women (see

Bluebeards

). Believing (incorrectly) that without a corpse, the authorities could not convict him of murder, he reduced all his victims to ash in an outdoor oven. Even without a single identifiable body, however, the authorities were able to assemble enough circumstantial evidence to send Landru to the guillotine.

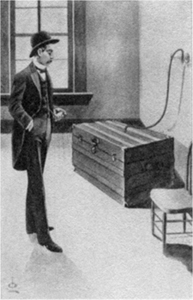

Dr. H. H.

Holmes

—

the turn-of-the-century serial killer and another notorious lady-killer—disposed of dozens of victims in the same way. When investigators finally broke into his rambling “Horror Castle” in a suburb of Chicago, they discovered both a basement crematorium and an oversized office stove that still contained the charred remnants of one of his ill-fated mistresses. Holmes’s most heinous crimes, however, were the cold-blooded murders of three young siblings—the children of his accomplice, Ben Pitezel. Two of these little ones were asphyxiated and buried in a basement crawl space. The blackened remains of the third, a ten-year-old boy, were found in the belly of a coal-burning oven.