The Air We Breathe (28 page)

Read The Air We Breathe Online

Authors: Andrea Barrett

“Eudora would never do anything to hurt you,” Irene said. “If she deceived you at all, it would only have been to keep you from being hurt.”

“You

would

take her side,” Naomi said. “You've done everything you could to come between us, you

took

her. You took my friend.”

“That's not true,” said Irene.

Click click click click click,

went the nails against the folders.

“Leo loves me,” Naomi said, “the way I love him. I see the way he watches me, I

know

. I made the mistake of telling Eudora and now she's trying to take him for herself, just the way you took her. The way you two take everything.”

Irene drew a breath. How terrible, she thought, not to be able to see what was real. Gentlyâshe wondered if she'd ever misread a person so badlyâshe said, “Leo has been mooning over Eudora for months now. He was watching

her,

not you. He's told Eudora how he feels. And I think she's beginning to have feelings for him as well. I don't approve, I think she should keep her mind on her work, butâ”

Naomi glared at her and then set her bag firmly on the floor. “Why are women like you so stupid?” she said. “You, my motherâboth of you too old and dried-up to understand how

anyone

feels.”

Reaching down, she pulled a handful of papers from her bag and waved them at Irene. Chins, ears, noses, eyes; at first Irene wasn't sure what she was looking at. Eventually, she made out Leo's face.

“

This

is what's real,” Naomi said scornfully. “The way I feel about Leo. Not that you'd know what it's like to look at someone's mouth and feel it on you, or to know how his hands would touch you⦔

For a second, Irene wanted to slap her. Of course she knew: when she and her husband were first married, the sound of his footsteps coming toward her in the dark could make her heart race like a greyhound's. He used to tease her by holding his right hand over her breast, so close he was nearly touching it, hovering until she lifted her body to meet him. And then years later, after he'd died and she'd moved to Colorado and thought she was past all of that, she'd been startled by the fierce charge that leapt between her and her brother-in-law when they were first experimenting with the Roentgen rays. She'd taken the job Dr. Richards offered as a way of saving her sister; she was here because of just those feelings. How upsetting that, to someone Naomi's age, she looked as if she'd always been old.

She calmed herself and raised her good hand to Naomi's shoulder. “I do understand,” she said: sympathetically, she hoped. “I'm fond of Leo myself and I can see why you'd be drawn to him. His intelligence, and his desire to learn; it's touching. He told me once that in Odessa he earned money for his laboratory fees by cleaning out latrines. You work hard yourself, I know. You must feel like that's a bond between you.”

Naomi shoved the drawings back into her bag. “When,” she saidâher hands were tremblingâ“when did he live in Odessa?”

“Before he moved here,” Irene said. “After his mother died and he left Grodno.” All those drawings, and yet Naomi seemed to know nothing essential about him; not even, perhaps, that he'd meant to be a chemist. “He told Eudora that during the first winter after he ran away from home, he slept on the floor in someone's pantry.”

In response, Naomi burst into tears, heaved the bag at Irene, and ran from the room. Papers, and something that looked like part of a garment, fluttered past Irene's shoulder. She had an instant to be grateful that the bag had missed her; there was something heavy inside, a book perhaps, which made a thudding sound as the bag hit the floor below the shelves.

We think the thudding sound was made by the antique fossil book given by Edward Hazelius as a Christmas present to Miles, which Miles then gave to Naomi and which Naomi must have wanted to give Leo. The stolen shirt lay on top of the book, along with the heap of drawings. Below it, we think, lay the third pencil. In the letters Eudora had started writing once she was over in France and working in the hospital, she'd tried to explain to Irene, and to herself, the evolution of her feelings for Leo. Without understanding the implications, she described the afternoon she'd found Naomi rummaging through Leo's locker.

I was ready to hit her, when I saw her there

.

I should have known then how I felt about Leo.

I

should have known, Irene would tell us later, as we leaned against the kitchen counters and nibbled the sunflower seeds she'd brought. But on that May night all she knew was that Naomi was crying. She followed Naomi into the corridor, leaving the bag where it fell. Behind her, we hypothesize, the pencil crushed between the book and the floor let out a little spurt of exceptionally hot flame.

WE HAVE THE

letter from Eudora's brother; based on that we imagine Naomi's life in New York. Probably, we think, she is fine. Upset, perhaps; grieving over the loss of Leoâbut for all that basically fine. Unaware of what she has done, what she has caused. If she saw a report about the fire in the newspapers, did she figure out her own role? We think not; she paid no attention to anything but her own feelings, and it wouldn't have occurred to her that her actions might affect other people. We imagine her dressed in a streetcar conductor's uniform, collecting fares and smiling at passengers as the car traverses a stretch of Brooklyn, perhaps flirting with a young man who looks like Leo. A girl, still; not quite twenty years old. In time someone else will catch her eye. Who knows what will happen then? She doesn't know that Leo was forced to leave, that Irene will always whisper, or that the clearing has expanded by three stones.

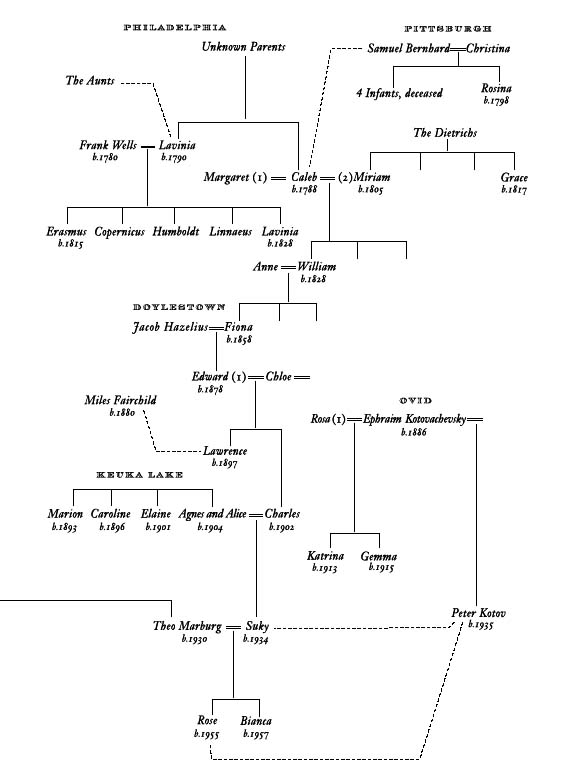

What she knows is that she escaped. Leo escaped as well, which seems lucky given the climate these days. When he left, he couldn't imagine how he'd make his next life. He went to Ephraim, whom he trusted, but soon he found that Ovid didn't suit him. Too much family, he wrote Dr. Petrie, all those cousins speaking Yiddish: exactly what he didn't want. One of Ephraim's friends found him work not far away, at a winery in Hammondsport.

A pretty village, beautiful hills,

he wrote to Irene. (He writes to Irene and to Dr. Petrie; not, so far, to the rest of us.)

A chance to work once more with grapes and the chemistry of fermentation, as I did long ago in Russia. I have my own laboratory.

He felt safe sending letters through the mail, knowing that Miles, to everyone's great relief, wasn't here to intercept them. In January, against the advice of his doctor, Miles left Tamarack Lake. No one, he supposedly said, could produce cement like he could, and so he went back to run his plant: his contribution to the war. When he left, it was like a patch of bad weather blowing out. The tops of the trees reappeared, and the tops of the mountains. The stars above the mountains, and the moon. We could see each other. We could see where we lived, what we had done, and what we still had left.

How innocent we seem to ourselves, now, when we look back at our first Wednesday afternoons! Gathering to learn about fossils, poison gas, the communal settlement at Ovid, about Stravinsky and Chekhov, trade unions and moving pictures and the relative nature of time, when we could have learned what we needed about the world and the war simply by observing our own actions and desires. We lived as if we were already dead, as if we'd died when we were diagnosed and nothing we did after that mattered. We lived as if nothing was important.

Despite the coldâit is ten below zero on this February dayâwe've walked through the snow to the garden behind our old solarium, the place where we were first joined. Around the fountain, shut off for the winter, we draw together as Abe begins to read the pages we have made. Once we built ships and towers from the pieces of an Erector set. Now we build hypotheses. About what Naomi did, and how Miles felt, and who said what to whom. About how the pencil that disappeared from Leo's locker ended up being used, almost accidentallyâmore and more, we think it started the fireâin Irene's laboratory. And about how all of us are to blame.

Abe reads, then Pietr reads, then Sophie, and then the rest; the sparrows perched on Hygeia's shoulders rise; words mingle in the air. If the voice we've made to represent all of us seems to speak from above, or from the grave, and pretends to know what we can't, exactly, knowâwhat Miles was thinking, what Naomi meantâthat's our way of doing penance. Singly, we failed to shelter Leo. Singly, then, we've forbidden ourselves to speak.

This is what happened,

we say together.

Thisâthis!âis what we did.

I'm grateful to the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers of the New York Public Library, for a fellowship that made possible much of the research for this novel, and to the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, for a fellowship that enabled me to write it. Numerous libraries large and small were helpful, but I'm especially grateful to the Saranac Lake Free Library. Rich Remsberg uncovered marvelous photographs that inspired me and provided crucial details. Ellen Bryant Voigt's wise counsel led me to the title. Jim Shepard and Karen Shepard offered sympathetic, truly helpful readings of the final draft, while Margot Livesey's brilliant comments on many drafts along the way improved the book immensely; the failures are mine alone.

Although this novel is set in and around an Adirondack village that resembles Saranac Lake, New York, the village of Tamarack Lake and all its inhabitants are invented, as is the institution of Tamarack State. Mendeleeff's book is real, though; Leo and I used the same edition.