The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society (32 page)

Read The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society Online

Authors: Chris Stewart

‘This,’ said Juan, dipping his finger and licking it, ‘is the best stuff of all. But the honey-buying public prefer it without the dead bees.’ He fetched me out one of the few remaining jars of the previous year’s honey, and took off the lid for me to approve. The honey was dark and thick like malt, and gave off a heady scent of orange and almond blossom, mountain herbs and that mysterious essence of the bee.

Juan had some watering to see to before we could stop for a drink, so picking up his mattock he strode towards his terrace of maize. I followed him into the forest of tall stems, laced with rivulets of running water, as he gave here a chop, there a poke with his mattock, adjusting the flow across the stony earth. It was cool and lush, a dim green penumbra of respite from the dust and glare outside. The plants, thick with leaf, towered way above our heads, and each was hung with several fat cobs of corn. I couldn’t help wondering where all the water was coming from, as there was not this much water at the moment in the whole

acequia.

‘I have a tank now,’ he explained, with a noticeable glint of pride. ‘Come, I’ll show it to you.’

As we walked, he asked me about the high pastures which he’d heard were very dry. ‘There’s nothing there, not a stitch of grazing,’ I told him and then voiced my worries about Antonio Rodríguez, whose sheep grazed the land up there. ‘It must be desperate for him,’ I said, ‘trying to keep this new flock of sheep alive. I don’t know how he manages… And being all on his own, too, it must weigh hard on him.’

I had got to know Antonio a decade ago, when I spent five days and nights with him helping to take his sheep down from the mountains to the coast at Almuñecar – a transhumance, as it is called, now virtually extinct in Spain. Even then it was hard going, crossing not just hillsides but dual carriageways. Antonio is the gentlest of souls, a man whose heart brims with goodness and generosity, and at forty-five he longs for a wife and children. Vain hope, because local girls don’t want anything to do with the life of a shepherd; it’s just too damn hard.

‘But he’s not on his own,’ said Juan, looking at me in surprise. ‘For all his troubles, Antonio is happy as can be; he’s absolutely head over heels in love with his little

daughter

. She’ll be coming on for two by now.’

‘Daughter? I didn’t even know he had a woman…’ I burbled.

‘Yes, he’s been married three years now. His wife is Moroccan from the High Atlas; she’s no stranger to the hard life – she loves it up there. You couldn’t find a happier family.’

This, I thought to myself, is about the best news I’ve heard all year. It seemed so unexpected and yet so right. And then, emerging again into the sunlight, Juan led me up a steep path, at the top of which we found ourselves

looking

into an enormous circular concrete tank. He turned to me for my reaction.

I considered the construction in silence for a moment, then, as its enormity registered, exclaimed:

‘Hombre!

That is one hell of a tank, Juan. Must be half a million litres.’

‘Six hundred thousand,’ he said proudly. ‘It cost five pesetas a litre to construct. Three million, I ended up paying.’ Spain uses the euro now, but sums of this magnitude are

still calculated in pesetas – and this, £15,000 near enough, was an enormous sum of money for a subsistence farmer to spend.

Juan showed me the outlet, where a small river was gushing from the tap and flowing down a channel to course among the maize. It was an impressive set-up, and the maize looked good and healthy, but it also seemed a huge amount of effort. Surely, I suggested, it would work out cheaper and easier to dispense with the crop altogether and buy in grain from the feed centre.

‘That’s true, Cristóbal, but you never know what you’re getting in those sacks,’ he replied thoughtfully. ‘It probably comes from America and therefore it’s probably

genetically

modified, and I don’t think we’re ready for that in the Alpujarras yet. I keep my own seed from year to year. Also there’s more to a crop of maize than the grain: there’s the leaf for forage for the mule, and the stalks for bedding, and once we’ve taken the grain from the cobs, the

panochas

make good fuel for the fire. And besides…’ – he paused a moment for emphasis – ‘I like my field of maize. It’s green and cool in the summer. A

cortijo

is not a proper

cortijo

without a summer crop of maize.’

So that was it: it was as much an aesthetic, even an

existential

decision, a simple matter of keeping the pigs, mule and poultry happy. In my heart I applauded it. ‘But what about the wild boar?’ I asked. Everybody knows that if you grow maize or potatoes, you’re certain to have your crop destroyed by the

jabali.

There’s nothing in this world they like better than those succulent tubers and sweet cobs.

‘I’ve installed an electric fence,’ he explained. ‘They’re terrified of electricity. I’ve grown corn here five years now with not a whisper of trouble.’

This was the first time I had heard of anybody using an electric fence in the Alpujarras. Juan was embracing modernity, the pragmatic approach, with his concrete tank and his electric fence, while hanging on tenaciously to the traditional ways. Juan and Encarna work ferociously hard all the hours of the day and every day of the week except for Thursday mornings, when they walk down to the road and hitch a lift into town to go to market. And they work like this to sustain their traditional, self-sufficient way of life, almost as if it were an end in itself.

I looked at the low whitewashed house with its thick stone walls, the hens scratching about in the dust, the magnificent vine drooping with fat green grapes, the

geraniums

bursting exuberantly from old pots and tins, and was reminded of the simple unselfconscious beauty that I had first loved about the Alpujarras. It’s true that it isn’t to everybody’s taste – the poverty and apparent

shabbiness

put some people off – but there is an integrity to this beauty that has to be sifted from the rubbish and the thorns and dust. Moving to the edge of the terrace I looked down across the valley at our own farm, and wondered if we too had managed to preserve its intrinsic charm.

‘Cristóbal, why so thoughtful?’ asked Encarna, who was standing behind me wiping her hands on her apron. ‘Come on in. I have a special treat for you,’ she announced.

We ducked our heads and entered the little kitchen. Juan began busying himself tying up a string of bright red peppers, while Encarna stepped around her rough wooden table to the freezer humming away in the corner. Freezer… I did a double take. A freezer is the one convenience we lack and cannot have; our solar power system is just not up to it. Yet a freezer would make our lives very much easier.

It’s easy to forget that Juan and Encarna, living up here on Carrasco, have proper electricity.

‘You’ll find this is the best way to enjoy honey,’ she said, and laid an ornate carton of ice cream on the table.

‘I don’t believe it?’ I cried incredulously. ‘How on earth did you get ice cream all the way up here without it

melting

?’ To be honest, though, it was the incongruousness of finding ice cream at all in this bastion of bucolic orthodoxy that most surprised me.

‘In a cool box with extra ice packs,’ Encarna answered simply. ‘Our granddaughter brought it up on her motorbike a few days ago as a surprise. She said it was her favourite flavour. It’s called… Oh, I don’t know what it’s called… some foreign name.’

‘Tiramisú,’ I read. And, relishing my amazement, she plopped a spoonful into the bowl and covered it with a dollop of honey mixed with almonds. Bliss! Sheer bliss!

The next day, while driving into town, I found myself musing over Juan’s concrete tank. Spending such a large amount to water a few trees and some maize made no economic sense at all, and yet Juan and Encarna knew exactly what they were doing. They had invested their savings so that they could live the traditional life they had chosen on the farm they loved.

Wasn’t that what we were trying to do at El Valero? We similarly had to pay for the privilege of living on our own

cortijo.

If we were to sell all our oranges, our olives, almonds and lamb… even in the best of years it would not square the accounts. In terms of money, labour and time,

our mountain farm, like Juan’s, is an anachronism. But it’s a hell of a nice anachronism. We chose the farm for its simple functioning beauty and it would never be enough just to sit there and admire it – or even write about it, for that matter. We need to go on taking some active part in our landscape, ploughing its soil, planting its orchards, tending its trees. That’s how we keep a sense of who we are.

Fortunately Ana feels much the same, and Chloë, who has lived her whole life here, won’t even hear talk of living anywhere else, although of course within a very few years she may be off to university or making her way in the world. My hope is that she’ll always have El Valero to come back to, should she need to recharge her batteries or find the solace of home.

Chloë, however, was far less impressed by my

philosophical

maunderings than by the surprise of having ice cream served up on our very own

tinao

. I had managed to acquire a cool bag and to fill it with enough frozen ice packs and insulation to get a tub home more or less intact. It was fruits of the forest with mascarpone flavour – an almost unimaginable luxury.

Evening crept towards night, the heat lay limpid upon us, and one bowl led to another and then another. Before long the whole lot had disappeared and we were left looking at the box and feeling just the tiniest bit uncomfortable.

We savoured the vanishing treat in a bemused silence, broken only by the flapping of hundreds of moths around the bare bulb above the table, the insane screaming of hot cicadas, the booping of an owl in the riverbed, and the occasional quiet roll of abdominal thunder. It’s the heat that does it to you; it saps the strength, weighs down the limbs and drugs the mind. As a prolonged heatwave gets

underway, you find yourself not just slurring your words, but slurring your ideas. Your attitude takes a bashing too, and you get sloppy. You can only read the simplest stuff and even maintaining a lively conversation becomes an

impossible

task.

The fabulous ice cream was gone, and all that was left was the tub. I had the lid and was considering it carefully, while Ana paid similar attention to the box. We ran them round in our hands, considered the top and the sides and the bottom. I noted, wordlessly, how neatly the lid with its recessed rim would fit on the box. All in all, the thing seemed like a very marvel of ingenuity and design. The texture of it was firm, yet flexible, and there was an

agreeable

transparency to the plastic. I looked at Ana and she looked back at me, and in our look there was a wordless corroboration, each of the other’s thoughts (you get this sort of thing when you’ve been living together for a long time). Together, we were marvelling at this simple,

utilitarian

object of perfection and – in its way – its ineffable loveliness.

Gradually we became aware that our daughter was watching us in amazement.

‘Look at the pair of you. You’re like a couple of primates,’ she spluttered. ‘It’s only an ice cream tub, for heaven’s sake!’

Ana and I looked up at each other, lid and box in hand, and then at Chloë, and in one of those rare moments of perfect synchronicity all three of us exploded into laughter.

Ten years on from the publication of Driving Over Lemons,

Chris Stewart

talks about life at El Valero, what’s changed in his valley, how the success of the books has affected him and his neighbours, and whether he ever regrets leaving Genesis.

Chris, the first thing everyone always wants to know is – are you still living on the farm, at El Valero?

It’s funny how often people ask that. They tend to say: ‘Are you still living on that dump of a farm you describe in the books, or have you moved to some marble-clad villa in Marbella?’

Clearly those people have not read the books! Either that or I have failed absolutely to get the message across. The answer is a crystal-clear yes. After twenty years, we still greatly enjoy living here, and the only way we are leaving is in a box – and not even then, as a matter of fact, as both Ana and I would like to be buried beneath an orange tree on the farm.

Mind you, I do sometimes wonder if we could have stayed at El Valero without the books and the royalties we earn from them. A lot of farmers, and especially organic farmers, find they simply can’t get by without some other source of income. It was pretty fortunate that our source turned out to be writing books.

Do you still feel the same way about the farm as when you moved here?

I had just turned forty when we bought El Valero; Ana was a few years younger. Looking back, it was a good age for a move. We could manage the constant round of work and still have energy left to look about us and make improvements. I can’t imagine starting out on some of those schemes today – fencing off the hillside for the sheep, for example, was an absolute killer of a task.

Curiously, during the first years I grew convinced that the one thing we needed to put everything in order was a tractor – as if it was a universal panacea that would sweep away the drudgery of farm work. I remember thinking, when I was offered a contract for Driving Over Lemons, ‘Maybe, I’ll be able to buy that tractor.’

And when I got my first royalty cheque, I did buy a tractor – a ropey old model which had reached the end of its useful life in Sussex. It was a vehicle that should have been put out to rust rather than shipped to Spain, especially to a farm like ours. I drove it for a few weeks but found it completely terrifying, wobbling and tipping on the tiniest of inclines. Which is the way a hell of a lot of farmers go, with a tractor tipping on top of them. So I’ve kept a pretty wide berth from it ever since.

Did the success of

Driving Over Lemons

have any immediate impact, beyond buying tractors?

It gave us freedom from daily worries about money – that’s a very welcome thing. It was a relief to no longer be pitied by friends or family, who thought we had been daft to sink all our money into a subsistence farm. And I no longer had to tear myself away from the farm to go shearing in the gloom of the Swedish winter, or do the rounds so much in Andalucía. Not that I regret all those shearing expeditions in the high mountains. They gave me an insight into a vanishing way of life, a ready source of stories, and a lot of local friends. We would have had a very different experience of Spain if we hadn’t needed to go out and find paid work.

The book also carried some sense of vindication of the crazy decision we had taken when we upped sticks and moved here. Even my mother, who had always hoped I would live in a nice Queen Anne house in the south of England, volunteered that she now almost understood what it was that we saw in the place.

Just how tough was it in the early days?

I’m not sure we stopped to think about it. We weren’t exactly hand-to-mouth, as the shearing brought in enough for us to get by on, given that we had the fruits of the farm. We always

had fresh orange juice, olives, wonderful vegetables, and an occasional leg of lamb. But we were, I suppose, pretty close to the breadline, which I think did us good. It would be foolish to extol the virtues of poverty, but you can learn a lot from a few years of straitened circumstances. For us, it bound us as a family and rooted us on the farm. We had to make things work because that was how we fed ourselves.

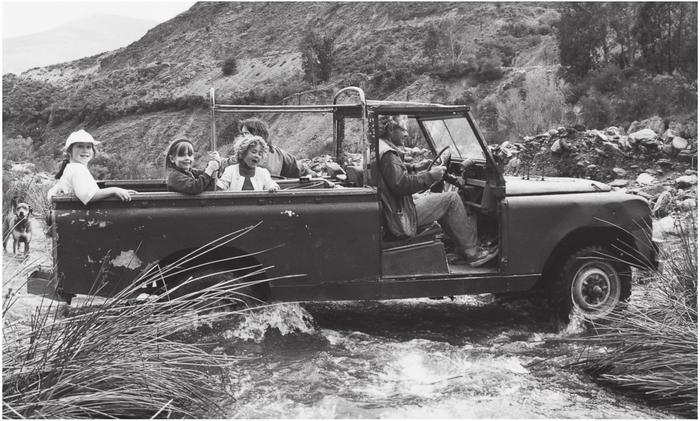

Driving over the river, with Chloë aged about five. The farm really is on the wrong side of the river – and we still have to ford it to get across.

Were you prepared for the book’s success?

Every publisher makes it their first task to tell an author, once they have commissioned their book, that they won’t make a bean out of it. And mine were the same: ‘Don’t give up the day job,’ they said. Not that there was any choice about that. If you’re a farmer, you can’t. I had no inkling that my whole life was going to turn around and the writing would become the thing that I do.

Although your books are sold as ‘Travel’, you actually stay at home!

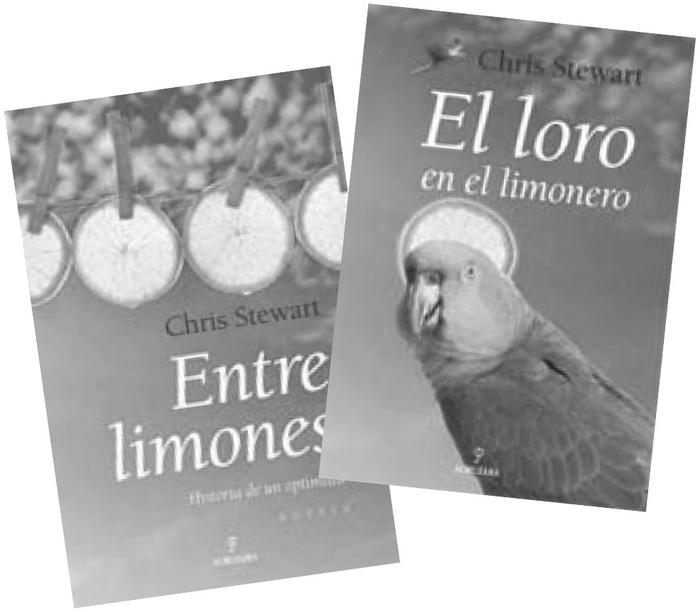

That’s right. I hardly move from the farm from one chapter to the next in Driving Over Lemons, though the orbit extends to Seville and back to Britain in

A Parrot in the Pepper Tree,

and

there’s a chapter in Morocco in the third book, The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society.

But the main things I write about are the kind of everyday things that happen to all of us, in our different ways. Children growing up and leaving home to become students, as has just happened to us with Chloë. And all the peculiarities of life – the snarl-ups and delights – which are perhaps odder for us because of the remoteness of where we live.

Of course, in Spain, where I have recently been published, they really can’t put my books under travel, so they put them under ‘Self-Help’, along with books on the spiritual path and harvesting your inner energy. Strange bedfellows.

You’ve become a bestseller in Spain over the past couple of years. Have your neighbours now read the books?

When

Driving Over Lemons

was published, Domingo – my nearest neighbour and the book’s true hero – got his partner Antonia to translate and read it to him…but only the bits in which he appeared. Later, when it came out in Spanish, he read a chapter every night before going to sleep. Of course, he never mentioned this to me, though he told Antonia that he enjoyed the book.

But the funny thing about Domingo is that he is not Domingo at all – he has a quite different name. For many months, as I was writing the book, I would tell him that I was writing a book in which he appeared as a major character. Would it be okay to use his name or would he rather I change it? ‘Me da igual,’ he would say in his typically Alpujarran way; ‘It’s all the same to me.’ I was pleased because I felt I had created an affectionate portrait of a good friend, and it felt right to use his real name.

Well, I asked him again and again, just to make sure, and each time received the same assurance. And then, at the last possible moment, he came up to the house, very animated, and said: ‘Cristóbal, I’ve been talking to somebody who knows about these things and he tells me that I could get into a lot of trouble as a result of this book – legal problems and family problems and God knows what else. So I want my name changed.’

I could see that somebody in a bar had been spreading a bit of

mala leche

–‘bad milk’ – as the

Spanish put it. I was a bit sorry about it, but he was adamant, so I set about changing the names of all his relatives and his farm, and so on. Of course, anybody local reading the book would still know exactly who Domingo was, but he didn’t seem to mind that. As far as he was concerned, as long as the character was called a different name, it wasn’t officially him.

Then, as time marched on, my-friend-aka-Domingo, inspired and encouraged by Antonia (who, of course, isn’t called Antonia), took up sculpture and started making a bit of a name for himself by creating the most dazzling bronze figures of animals. By this time

Lemons

was selling like hot buns. And so he decided to go for an alias – and to my great delight chose to call himself, for artistic purposes, Domingo.

What about your other neighbours? What was the reaction like from them?

There was a bit of everything. One woman in Orgiva complained very publicly that I had not painted an accurate picture of the people of the town, ‘because we don’t eat chickens’ heads’. Apparently

everything else was fine: it was just the culinary stuff that stuck in her throat, so to speak. Well, having comprehensively researched the subject of chicken head cuisine, I can say authoritatively that some Orgiveños do and some of them don’t. I know this because I’ve had the pleasure of sharing the odd chicken’s head myself.

The locals in general began to register the success of the book because people started to turn up clutching copies. This gave a bit of a boost to the drooping Orgiva economy, which made me popular with the café owners. Antonio Galindo, who owns the bakery, a café, two bars and a discoteca, embraced me publicly in the high street and said I had turned his fortunes around. So that felt good. And not long after, I was honoured to be the recipient of the Manzanilla Prize for Services to ‘Convivencía y Turismo’ (which loosely translates as ‘harmony between cultures and tourism’). This singular honour was manifested in the form of a tin sculpture of a manzanilla (camomile) plant – what the Spanish often call a pongo (as in the phrase

‘Dónde demonios lo pongo?’,

which means ‘Where the devil do I put this?’).

News of the award got into the national paper,

El Pais,

where it was seen by an anthropology professor, who then published a scathing letter stating that I had contributed more to the dilution and demise of Spanish culture than any other single person. That shook me a bit, and a few days later I was stopped on the road into town by Rafael, who farms olives, oranges and vegetables in Tijola, our nearest village. ‘I have just read your book, Cristóbal,’ he boomed. I hung my head to await the worst. ‘You are the greatest writer of the Alpujarra,’ he intoned. ‘You are…’, he paused searching for a very particular epithet, ‘a Rambo of the mind’.