The Art of Manliness - Manvotionals: Timeless Wisdom and Advice on Living the 7 Manly Virtues (25 page)

Authors: Brett McKay

Man to be great must be self-reliant. Though he may not be so in all things, he must be self-reliant in the one in which he would be great. This self-reliance is not the self-sufficiency of conceit. It is daring to stand alone. Be an oak, not a vine.

Be ready to give support, but do not crave it; do not be dependent on it. To develop your true self-reliance, you must see from the very beginning that life is a battle you must fight for yourself—you must be your own soldier. You cannot buy a substitute, you cannot win a reprieve, you can never be placed on the retired list. The retired list of life is—death. The world is busy with its own cares, sorrows and joys, and pays little heed to you. There is but one great password to success—self-reliance.

If you would learn to converse, put yourself into positions where you

must

speak. If you would conquer your morbidness, mingle with the bright people around you, no matter how difficult it may be. If you desire the power that someone else possesses, do not envy his strength, and dissipate your energy by weakly wishing his force were yours. Emulate the process by which it became his, depend on your self-reliance, pay the price for it, and equal power may be yours. The individual must look upon himself as an investment of untold possibilities if rightly developed—a mine whose resources can never be known but by going down into it and bringing out what is hidden.

Man can develop his self-reliance by seeking constantly to surpass himself. We try too much to surpass others. If we seek ever to surpass ourselves, we are moving on a uniform line of progress, that gives a harmonious unifying to our growth in all its parts. Daniel Morrell, at one time President of the Cambria Rail Works, that employed 7,000 men and made a rail famed throughout the world, was asked the secret of the great success of the works. “We have no secret,” he said, “but this—we always try to beat our last batch of rails.” Competition is good, but it has its danger side. There is a tendency to sacrifice real worth to mere appearance, to have seeming rather than reality. But the true competition is the competition of the individual with himself—his present seeking to excel his past. This means real growth from within. Self-reliance develops it, and it develops self-reliance. Let the individual feel thus as to his own progress and possibilities, and he can almost create his life as he will. Let him never fall down in despair at dangers and sorrows at a distance; they may be harmless, like Bunyan’s stone lions, when he nears them.

The man who is self-reliant does not live in the shadow of someone else’s greatness; he thinks for himself, depends on himself, and acts for himself. In throwing the individual thus back upon himself it is not shutting his eyes to the stimulus and light and new life that come with the warm pressure of the hand, the kindly word and sincere expressions of true friendship. But true friendship is rare; its great value is in a crisis—like a lifeboat. Many a boasted friend has proved a leaking, worthless “lifeboat” when the storm of adversity might make him useful. In these great crises of life, man is strong only as he is strong from within, and the more he depends on himself the stronger will he become, and the more able will he be to help others in the hour of their need. His very life will be a constant help and a strength to others, as he becomes to them a living lesson of the dignity of self-reliance.

A

N

A

ESOP’S

F

ABLE

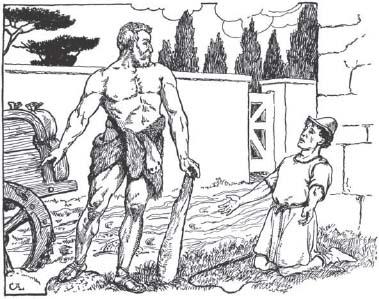

As a Wagoner drove his wagon through a miry lane, the wheels stuck fast in the clay, so that the horses could proceed no further. The man, without making the least effort to remedy the matter, fell upon his knees, and began to call upon Hercules to come and help him out of his trouble.

“Lazy fellow,” said Hercules, “lay your own shoulder to the wheel. Stir yourself, and do what you can. Then, if you want aid from me, you shall have it.”

Heaven helps those who help themselves.

“Do what thy manhood bids thee do

from none but self expect applause;

He noblest lives and noblest dies

who makes and keeps his self-made laws.”

—Richard Francis Burton

F

ROM THE ESSAY

“S

ELF

-R

ELIANCE

,” IN

E

SSAYS,

F

IRST

S

ERIES

, 1841

By Ralph Waldo Emerson

I read the other day some verses written by an eminent painter which were original and not conventional. The soul always hears an admonition in such lines, let the subject be what it may. The sentiment they instil is of more value than any thought they may contain. To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men—that is genius. Speak your latent conviction, and it shall be the universal sense; for the inmost in due time becomes the outmost—and our first thought is rendered back to us by the trumpets of the Last Judgment. Familiar as the voice of the mind is to each, the highest merit we ascribe to Moses, Plato, and Milton is, that they set at naught books and traditions, and spoke not what men but what they thought. A man should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light which flashes across his mind from within, more than the lustre of the firmament of bards and sages. Yet he dismisses without notice his thought, because it is his. In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts: they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty. Great works of art have no more affecting lesson for us than this. They teach us to abide by our spontaneous impression with good-humored inflexibility then most when the whole cry of voices is on the other side. Else, to-morrow a stranger will say with masterly good sense precisely what we have thought and felt all the time, and we shall be forced to take with shame our own opinion from another.

Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string. Accept the place the divine providence has found for you, the society of your contemporaries, the connection of events. Great men have always done so, and confided themselves childlike to the genius of their age, betraying their perception that the absolutely trustworthy was seated at their heart, working through their hands, predominating in all their being. And we are now men, and must accept in the highest mind the same transcendent destiny; and not minors and invalids in a protected corner, not cowards fleeing before a revolution, but guides, redeemers, and benefactors, obeying the Almighty effort, and advancing on Chaos and the Dark.

Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members. Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater. The virtue in most request is conformity. Self-reliance is its aversion. It loves not realities and creators, but names and customs.

Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist. He who would gather immortal palms must not be hindered by the name of goodness, but must explore if it be goodness. Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind. Absolve you to yourself, and you shall have the suffrage of the world.

What I must do is all that concerns me, not what the people think. This rule, equally arduous in actual and in intellectual life, may serve for the whole distinction between greatness and meanness. It is the harder, because you will always find those who think they know what is your duty better than you know it. It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.

“Self-reliance is a noble and manly quality of the character; and he who exercises it in small matters schools himself by that discipline for its exercise in matters of more momentous importance, and for exigencies when the help of others—readily proffered in ordinary cases—may not be offered, or, if offered, may be unavailing for his aid in the emergency.” —The Christian Globe

F

ROM

E

NDURANCE

, 1926

By Earle Liederman

Every man should be able to save his own life. He should be able to swim far enough, run fast and long enough to save his life in case of emergency and necessity. He also should be able to chin himself a reasonable number of times, as well as to dip a number of times, and he should be able to jump a reasonable height and distance.

If he is of the fat, porpoise type, naturally he cannot do all, if any, of these things; he has nobody to blame but himself, and his way of living that has brought his body into its condition of obesity.

Suppose—and it has happened many times—there should be a fire at sea or on lake or river; should one be half a mile or more from the shore, he would be mighty thankful to realize, were he compelled to jump for his life from the fire, that he could swim that distance and reach the shore in safety.

Suppose one were in a burning building and he had to lower himself hand under hand down a rope or down an improvised rope of bedclothing tied together to reach the ground in safety; he again would be thankful a thousand times that he possessed the strength and endurance in his arms and coordinate muscles that would enable him to save himself. Such things never may happen, and let us hope they do not, but what has happened always is possible to occur again—and, in fact, always is happening to someone.

I do not believe in everyone striving to be a long distance swimmer, a long distance runner, or any kind of endurance athlete.

But he should be able to swim at least half a mile or more; he should be able to run at top speed two hundred yards or more; he should be able to jump over obstacles higher than his waist; and he should be in condition to pull his body upward by the strength of his arms, until his chin touches his hands, at least fifteen to twenty times; and as for pushing ability, he should be able to dip between parallel bars or between two chairs at least twenty-five times or more.

If he can accomplish these things he need have no fear concerning the safety of his life should he be forced into an emergency from which he alone may be able to save himself.

“I was taught to endure labor, to want little, and to do things myself.” —Marcus Aurelius

F

ROM

W

ALDEN

, 1854

By Henry David Thoreau

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion. For most men, it appears to me, are in a strange uncertainty about it, whether it is of the devil or of God, and have

somewhat hastily

concluded that it is the chief end of man here to “glorify God and enjoy him forever.”

Still we live meanly, like ants; though the fable tells us that we were long ago changed into men; like pygmies we fight with cranes; it is error upon error, and clout upon clout, and our best virtue has for its occasion a superfluous and evitable wretchedness. Our life is frittered away by detail. An honest man has hardly need to count more than his ten fingers, or in extreme cases he may add his ten toes, and lump the rest. Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand; instead of a million count half a dozen, and keep your accounts on your thumb-nail. In the midst of this chopping sea of civilized life, such are the clouds and storms and quicksands and thousand-and-one items to be allowed for, that a man has to live, if he would not founder and go to the bottom and not make his port at all, by dead reckoning, and he must be a great calculator indeed who succeeds. Simplify, simplify.