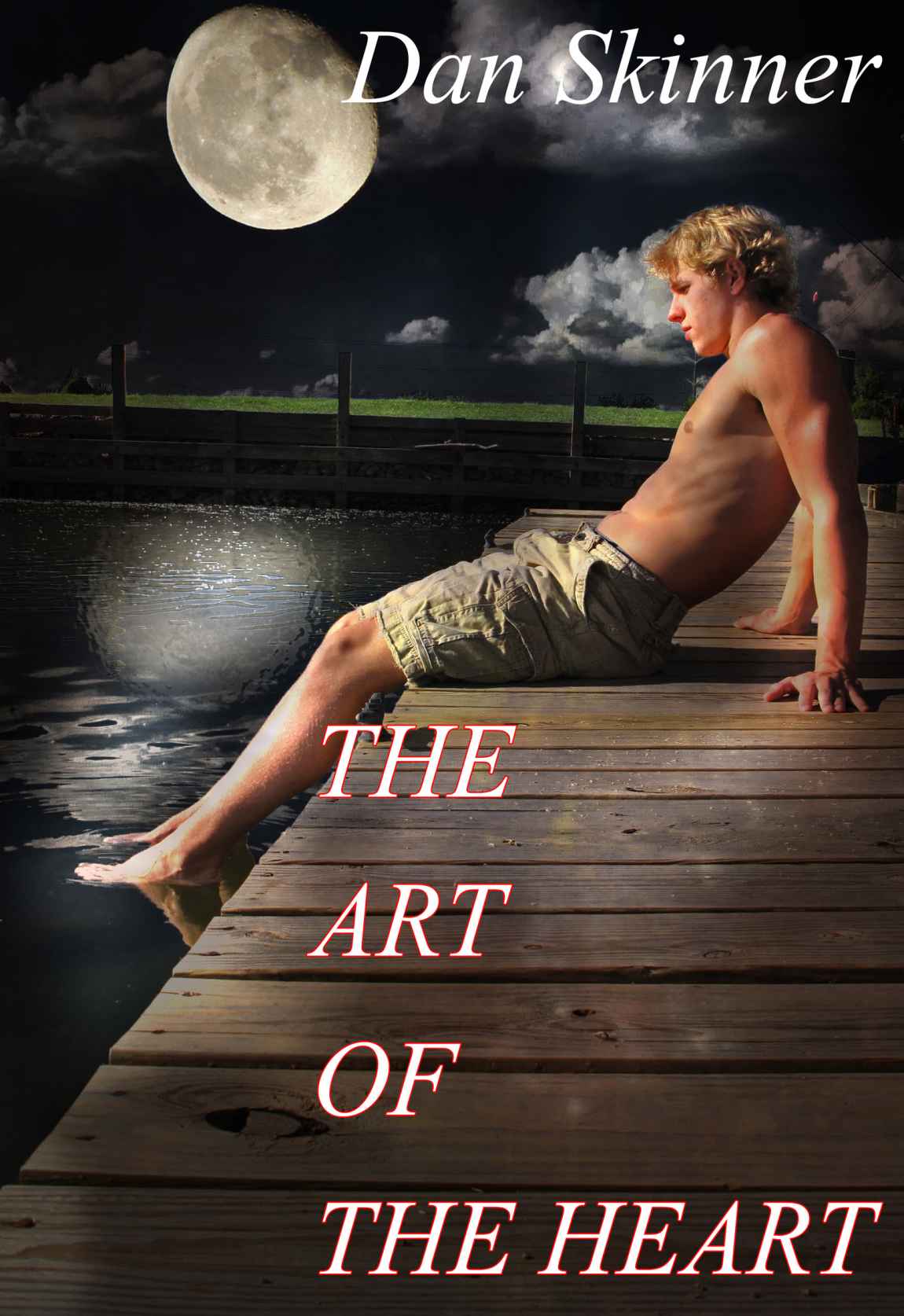

The Art Of The Heart

Read The Art Of The Heart Online

Authors: Dan Skinner

The Art of the Heart

Dan Skinner

The Art of the Heart is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 201

4 by Dan Skinner

Cover Art by

Dan Skinner

Edited by

Tina Adamski

Formatted by Laura Harner

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by

Dan Skinner

ISBN:

978-1-937252-85-4

Warning: All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without written permission, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

The unauthorized reproduction or distribution of this copyrighted work is illegal. Criminal copyright infringement, including infringement without monetary gain is investigated by the FBI and is punishable by up to five years in federal prison and a fine of $250,000.

My special thanks to Laura Harner and Tina Marie

Adamski, without whom this book would not be.

The author acknowledges the trademarked status and trademark owners of the following

trademarks mentioned in this work of fiction:

Ford Galaxie: Ford Motor Company

John Deere

: Deere & Company

Mobil

: Exxon Mobil Corporation

Slo

-Poke: Atkinson Candy

M&Ms

: Mars, Incorporated

Pepsi

: Pepsico

Kool

Aid: Kraft Foods, Inc.

Chapter One

In 1965, the town of Sweetwater, Missouri was three blocks of paved road pointing North and South in the middle of the state. One end of the road was aimed at Highway 70 that led to the big towns and cities, and the other end abruptly dumped into a gravel road that was Rural W, a serpentine lane that led to six farms, three on either side. Sweetwater, the whole of it, including the one lane of town and six farms, was eight miles wide and ten miles long; popul

ation five hundred–if you counted a few of the inhabitants twice. The actual town was called a

one-eacher.

It had one each of everything: one diner, one gas station, barber shop, general store, grade school and movie theater. Only the movie theater, which everyone called

the picture show

, had air conditioning in the summer. That made it a popular gathering place during the Missouri heat. More than half of the population was under the age of twenty. Many of those were boys, draft-age, who’d been exempt from the draft because their absence would cause the family hardship. It took every family member of those households to work the farms. The family was what made the farms work.

Back then, 1965 Missouri had a smell: fresh, unpolluted. Green. Earthy. The interior of buildings smelled like the lives of the people living in them. The pipes they smoked, the licorice they chewed,

the coffee that percolated in pots on the stoves. Cars were big and metal with motors you could hear a block away. People took time to wash and wax them by hand on Saturday afternoons. Friends and neighbors would gather to watch while trading stories and sharing beers.

The definition of a simpler time could be discerned in the nature of the acts of youthful rebellion. Those came with long hair on the boys, drinking and cigarette smoking. The drug culture that had slowly crept into the bigger cities hadn

’t wormed its way into the rural heartland yet. But moonshine could be found and purchased in the next county of Clarksville. A younger farmer there supplemented his income providing the youth with an affordable, if nasty-tasting vice. Sweetwater’s sheriff turned a blind eye to this minor nuisance unless something big happened. He had one jail cell, no deputy and would have to care for and feed anyone arrested over the weekend when most of the drinking and the subsequent shenanigans occurred. The sheriff, a thirty-five-year old bachelor, was romancing the new eighth grade school teacher and liked to have his weekends free for this pursuit. So unless you destroyed property, brawls and bruises became family problems. If you couldn’t afford moonshine or the fifty cents it cost to see a show, the only other entertainment was petting or necking in the backseat of a car, or the other clandestine spots the teenagers knew well. Unless your name was Zac Weston. Seventeen years of age. Virgin.

Nicknamed Two-Tone because his eyes were two different colors, one green and the other blue, Zac was six feet of skin and bones. He was pale except for

a farmer’s tan on his neck and arms during the summer months. His nose and cheeks were sprinkled with freckles and his collar-length hair was the color of rust, a dark brown just begging to be red. His bangs were long enough that when he dipped his head, he could keep his face hidden from everyone. Not that he had a bad face. When he was younger his nose was long and seemed ill-fitted and his ears stood out a bit, but as he came into his later teens he grew into them, although no one would know that. He stayed hidden beneath his auburn veil. He was shy; stayed to himself. He never took off his shirt. Never wore shorts.

Most of the town thought he was slow. That wasn

’t the case. He wasn’t by any means mentally challenged. He was as smart as the next boy his age. He was just quiet. There was a reason for that, but none he would share. It was much easier for everyone to just believe he was slow. There were other terms for what he was, but none of those were considered acceptable. He’d heard them all: queer, fairy, girlie-boy.

Zac was the only child born late in the life of his father Byron Weston and his second wife, Margret. They were both in their mid-forties when he became their

little surprise

and

miracle

. Byron had lost his first wife in childbirth twenty years earlier, and waited another fifteen to remarry. They owned Cloverfield farm, the largest of all the farms in Sweetwater, located at the very end of the gravel road. Cloverfield was over one hundred acres of soybeans and corn. They had six dairy cows and a couple dozen chickens. These were primarily for personal use. Meg Weston, Zac’s mother, made homemade butter, and they sold milk to a couple of the other farms that didn’t have dairy animals.

The care of the farm animals was primarily Zac

’s duty. He’d rise before dawn to feed and milk and gather eggs. By sunup he’d had his breakfast, and would be about the rest of the farm chores with his dad. They lived in a two-story home that sat at the front of their land, fifty yards from the gravel road that ended at their gate. The house was a simple white structure, old-style Americana: black shutters, front porch with a porch swing that could seat two comfortably. There was a rocker and a spittoon for tobacco chewers. Windows were large with sheer curtains and window seats on the inside of the bigger ones. At night as one drove up to the gate and the lights were on in the house, you could see clear through it. Houses like these always had welcome written on them like an invitation.

Zac had graduated high school, would never go to college. Every bit of money the farm made went back into the farm. It was a self-sustaining, endless cycle for farm families. Very few young people ever made it to higher education. Farm children became farmers. Escape was a difficult to attain dream. Those who did flee to the city often returned. They were too innocent and naïve. The cities were where monsters with crafty souls took advantage of those who were bred to have consciences

.

The pale, almost-red haired boy had a room in the back of the upstairs of the large house. It was separated from his parents by a sewing room, a furniture refinishing room and another that was completely empty save for a few pieces of unused furniture. Houses like this one were built for large families. Zac knew with his parents

’ age and his own sexual preference, there would never be one in his lifetime. The huge spaces and wooden floors and doors always made it sound hollow and empty. All the more difficult for keeping secrets. Unless you were a very quiet boy.

Zac lived his life in the comic books he collected. His closet shelf was neatly stacked with them. His parents thought the magazines to be a harmless pastime. A hobby. But Zac bought them because of the beautiful men with gorgeous bodies

in revealing tights and trunks. They were as close as he could get to what he desired.

He had discovered this desire when he was thirteen. He was riding with his dad into town to buy yeast and flour, baking soda and sugar for his mom to make her homemade bread. There was nothing like bread hot from the oven with fresh sweet butter melting on it. The old

‘59 Ford pickup churned up a trail of beige dust behind it as they bumped their way toward the McHenry farm. The McHenrys had the second largest farm after their own, and grew alfalfa and corn. They also had an apple orchard that they shared with the whole town during apple-picking season. Zac’s mom made apple pies for every farm family. For a couple of months every fall, the house at Cloverfield would smell of apples and cinnamon.

That

summer had been scorching during his thirteenth year. But Zac still wore his t-shirts and long jeans. He didn’t like to expose his gangly white limbs to anyone for ridicule. He’d grown accustomed to the heat and sweat.

As they neared the McHenry property, Zac could see their green John Deere tractor parked at the edge of the cornfield. The corn had been harvested and it was now time to mow down the stalks and turn the field. Someone was lying on top of the tractor basking in the white-hot summer blaze. He could just make out the battered cowboy hat covering

his face.

The

McHenrys had six children. Only two were boys. Rory and Dale were the oldest and youngest respectively. Zac could tell by the long contour of the body stretched across the top of the tractor that it was the elder of the boys. Rory had just turned sixteen, but had been showing the signs of impending manhood two years earlier. He was six feet tall, had muscles where they hadn’t been before, and a smattering V-line of fine blond hair across his chest and stomach. He was shaving. Every two or three days his dark whiskers would outline his square jawline. He lay shirtless on the tractor in a pair of cutoff jeans rolled up to mid-thigh. He was tan and shone like glistening copper in the sun.

As their pickup rattled closer to their farm, he lifted his hat and looked down the road toward them. Even from that distance Zac could count each ridge in the washboard of his abdominal muscles. A long muscled arm poked high in the air

and waved the cowboy hat at them. He jumped from the tractor and trotted across the short span of field toward them as they approached. Zac’s dad stopped the truck, and a low, dry cloud of dust swirled its way in through the windows. All hands waved it away as Rory met them at the passenger side and leaned in. His face was walnut brown making his teeth seem an extraordinary shade of white as he smiled at Zac.

“

Hey there, Two-Tone! Mr. Weston!” he greeted them.

Zac could smell the heat coming off the older teenager

’s skin. He was dotted with perspiration. He tried not to stare, but the irresistible gravity driven by his curiosity made it impossible to fight. He thought Rory was the handsomest boy in all of Sweetwater. His brownish hair was straight and long and streaked with gold. His eyes were so light a shade of blue they mocked a summer sky. His brows and lashes were a striking light blond. He always seemed to be smiling. His nearness made Zac’s insides flutter like a butterfly in a cupped palm.

“

What can we do for ya, Rory?” Zac’s dad asked, hand still whisking the backdraft of dust away from his face.

“

Dale was s’posed to fill the tractor with gas and forgot. Was wonderin’ if you had a spare gas can and could drop me at the station in town?”