The Articulate Mammal (25 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

‘Wugs’ you should say, if you understand the rules which underlie English plurals. And that is the reply given almost unanimously by a group of children who were shown this picture. The researcher wanted to prove that they hadn’t just memorized each plural as they heard it, but had an internalized ‘rule’ which could apply even to words they had never heard (Berko 1958).

And it wasn’t just wugs the children coped with correctly, so no one could argue that they misunderstood the word as ‘bugs’. Another picture showed a man standing on the ceiling, with the words: ‘This is a man who knows how to bing. He is binging. He did the same thing yesterday. Yesterday he – ?’ ‘Binged’ said nearly all the children tested. Admittedly, they had higher results for words they already knew. More children got the plural of GLASS right than the plural of a nonsense word TASS (TASS and GLASS rhyme in American English, having the same vowel as the word MASS). But no one can doubt that they were applying ‘rules’ (linguistic patterns) which they had worked out for themselves.

An even more striking example of the child’s ability to generalize patterns is the development of irregular verbs such as COME and CAME, GO and WENT, BREAK and BROKE. As noted in

Chapter 4

, children start by acquiring the correct

irregular

forms for the past tense, CAME, WENT, BROKE. Some of these are acquired fairly early, since they are very common words (Ervin 1964; Slobin 1971a). One might suppose that practice makes perfect, and that these words would remain correctly formed. But not at all. As soon as children learn the

regular

past tense for words such as HELPED, PLAYED, WALKED and WASHED, they give up using the correct irregular form, and start using the overgeneralized forms COMED, GOED, BREAKED. And when they re-acquire the irregular verbs, they first produce semi-regular forms which have a normal ending, as in LOST, LEFT (Slobin 1971a). All this indicates that children have a strong tendency to look for and apply ‘rules’ (linguistic patterns), at least as far as English noun and verb endings are concerned.

This mastery of past tenses has been simulated on a computer, which went through the same stages as young children. A ‘learning network’ was presented with sets of verbs, some regular, some irregular. It connected together verbs and endings by picking up on the frequency of the forms it was exposed to. First, it learned the irregular verbs, then it started to over-regularize them, with forms such as GO-ED and HIT-ED. Finally, it correctly mastered the past tenses of almost all the verbs fed into it (Plunkett 1995; Elman

et al.

1996).

Two opposing conclusions could be drawn from this: either language learning is straightforward, graspable even by a well-programmed computer; or word endings are a small and not very difficult part of language: even Genie, the deprived teenager could handle them (

Chapter 3

). It is perhaps not surprising that children are able to generalize plurals and past tenses. After all, word endings tend to rhyme. Children are known to have a fascination for rhymes, and they frequently make up little poems such as ‘I am a bug, sitting on a rug, warm and snug, with my mug.’ So the extension of an -S from BUGS, MUGS and RUGS to WUGS is not particularly startling.

Incidentally, not all children add on endings straightforwardly. A partially blind child, Seth, acquired his word endings via ‘phonological toeholds’. He

reproduced the rhythm of the words, and often placed an indistinct ‘filler’ sound where a syllable should be. But these became accurate endings only gradually (Peters and Menn 1993).

What further evidence of linguistic patterns can we find? We can note that from the moment children place three or more words together, they seem to show an instinctive awareness of

hierarchical structure

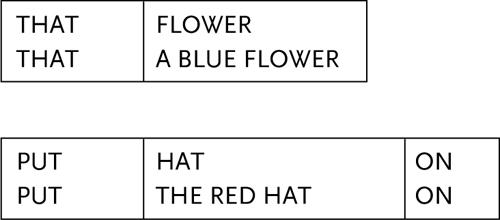

, the realization that several words can fill the same structural ‘slot’ as one:

However, the sentences just quoted look like ordinary adult ones with a few words left out. This means that we need more evidence to test the claim that children are operating with an internalized set of ‘rules’ which do not correspond to the adult ones. Several researchers have hunted for this evidence, and claim to have found it. Ursula Bellugi of Harvard University noted: ‘We have found several periods where the child’s sentences show systematic deviations from adult language, as if they were constructed according to a different set of rules’ (Bellugi 1971: 95). She and Edward Klima analysed the development of negatives and interrogatives by studying the utterances produced by the now famous Harvard trio Adam, Eve and Sarah (Klima and Bellugi 1966). As already noted in

Chapter 4

, the families of these children were totally unacquainted and independent of one another, and each child heard a different set of sentences as ‘input’. Nevertheless, the children passed through surprisingly similar stages in their progress towards adult constructions. Each phase was characterized by identifiable patterns and the utterances could not be regarded merely as bad imitations of adult speech. The children seemed to be devising hypotheses to account for the regularities in the speech they heard around them. The development of negative sentences, outlined below, shows this clearly.

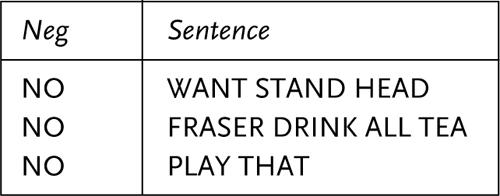

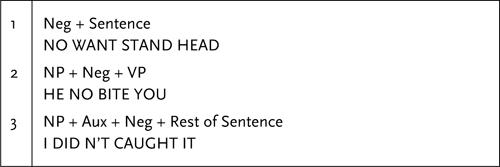

At first, Adam, Eve and Sarah seemed to be using a primitive self-instruction, ‘Put NO or NOT in front of the whole sentence.’

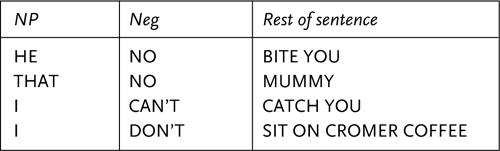

But this phase did not last long. Next came the realization that the negative goes

inside

rather than in front of the sentence. The children devised a new ‘rule’ which said, ‘Put the negative

after

the first noun phrase and before the rest of the sentence.’

At this stage, CAN’T and DON’T seemed to be treated as alternatives to NO. The children had not yet realized that they consisted of

two

elements. To them, CAN’T and DON’T were single negative units which could be substituted for NO or NOT. However, this substitution was not completely free. Just as in correct adult speech you never find CAN -ING (e.g. *I CAN SINGING) or DON’T -ING (e.g. *I DON’T SMOKING) – so the children never said * I CAN’T CATCHING YOU or *I DON’T CRYING. They had grasped the fact that CAN’T and DON’T do not occur before verbs ending in -ING.

The next stage came when the children realized that CAN’T and DON’T contained two separate elements, CAN + NOT, DO + NOT. This was guaranteed by the fact that CAN and DO began to occur in the children’s speech in non-negative sentences. This led to a more sophisticated negative rule in which the negative was placed in the

third

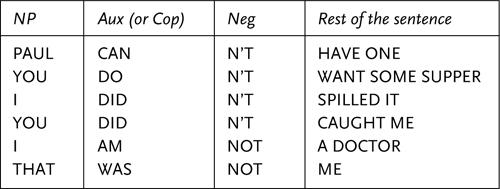

slot in a sentence, after the noun and auxiliary or copula and before the rest of the sentence.

The difference between this and the standard adult rule was that the children had not yet realized that the tense need only be included once.

A final stage occurred when the children amended sentences such as YOU DIDN’T CAUGHT ME to YOU DIDN’T CATCH ME.

So, independently, Adam, Eve and Sarah each went through similar intermediate stages in their acquisition of the negative:

Each of these can be regarded as a hypothesis to account for the rules of negation in English. The first is a simple hypothesis. The second is slightly less simple, and the third is almost the same rule as that used by adults. Klima and Bellugi are justified in their remark that ‘It has seemed to us that the language of children has its own systemacity, and that the sentences are not just an imperfect copy of those of an adult’ (Klima and Bellugi 1966: 191).

So Chomsky (1965) may be superficially right to regard the child as a miniature scientist who makes successive hypotheses to account for the data. But there is one major difference. When a scientist discards a hypothesis, he abandons it totally, and works only with the new one he is testing. Children do not behave like this. The stages do not follow one another cleanly and suddenly – they overlap quite considerably. As Klima and Bellugi note: ‘A characteristic of child language is the residue of elements of previous systems’ (Klima and Bellugi 1966: 194). For example, beside I AM NOT A DOCTOR, IT’S NOT COLD, and THAT WAS NOT ME, the children still produced sentences such as THIS NOT ICE CREAM, I NOT CRYING, PAUL NOT TIRED.

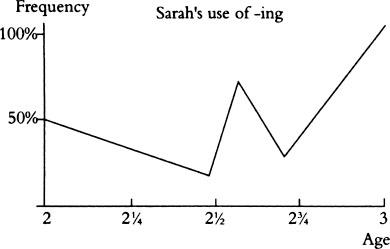

This type of fluctuation is noticeable in all aspects of child language. For example, Roger Brown noted, in the case of word endings, that children do not ‘abruptly pass from total absence to reliable presence. There is always a considerable period, varying in length, in which production-where-required is probabilistic’ (Brown 1973: 257). When he analysed the speech of the child Sarah, he found extraordinary swings in her use of the suffix -ING. At the age of 2 years she used it correctly 50 per cent of the time in sentences such as I (AM) PLAYING. But 6 months later this had dropped to 20 per cent. One month after this it shot up to 80 per cent, then went down again to around 45 per cent. She was over 3 years old before -ING occurred steadily and correctly in all her utterances.