The Articulate Mammal (27 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

7

____________________________

PUZZLING IT OUT

Exactly how do children learn language?

Teach your child to hold his tongue, he’ll learn fast enough to speak.

Benjamin Franklin

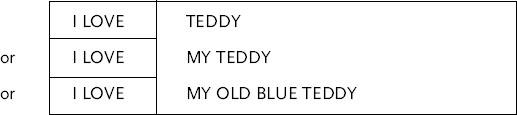

Children learn language so efficiently and so fast because they know in outline how languages behave. So far, it has not been very difficult to show that children have some inkling of what languages are like. They seem to realise that language is rule-governed – that a finite number of principles govern the enormous number of utterances they hear going on around them. They also have an instinctive awareness that languages are hierarchically structured – the knowledge that several words can go in the same structural slot as one. A child might say:

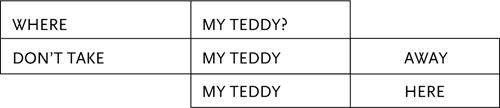

Furthermore, children realize that language makes use of operations which are structure-dependent, so that each ‘slot’ in a sentence functions as a unit which can be moved around, as in:

However, an inbuilt knowledge that language is rule-governed, that it has a hierarchical structure, and that it makes use of structure-dependent operations by no means explains the whole of language acquisition. We still need to know exactly

how

children develop language ability so efficiently. We would also like to find out

why

many English children follow similar paths in the development of their language. These are mysteries which cannot just be swept aside with vague assumptions of ‘innate programming’. We must investigate the matter more fully.

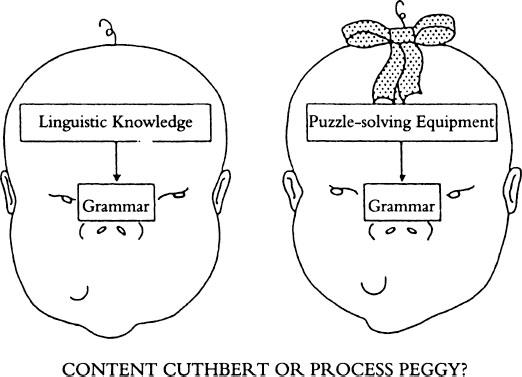

CONTENT CUTHBERT OR PROCESS PEGGY?

Over the past half century, two types of explanation have been put forward to account for the seemingly mysterious nature of language acquisition. First of all, there was Chomsky’s

content

approach. Second, an alternative, and possibly more plausible,

process

approach has been proposed. What is the difference between these two? Briefly, a content approach postulates that a child’s brain naturally

contains

a considerable amount of specific information about language. A process approach, on the other hand, suggests that children have inbuilt puzzle-solving equipment which enables them to

process

the linguistic data they come across. Each of these approaches has inspired a considerable amount of research. Both therefore need to be looked at carefully.

A content approach, such as Chomsky’s, claimed that children come to language learning with certain expectations. They are pre-wired with some quite specific information about language, and so approach the data they hear with advance knowledge. Of course Chomsky has never assumed that this knowledge is ready waiting, the moment the child is born. It takes time to mature. But when the time is right, it requires relatively little exposure to language for the knowledge to emerge. It may be like the growth of teeth or breasts. Given normal surroundings, these appear without any great effort on the part of the acquirer.

However, Chomsky’s theory that children innately contain large chunks of specific information about language always was, and still is disputed. Other researchers claim that, instead of possessing advance information, children are born with some sort of processing mechanism which enables them to analyse linguistic data. They suggest that:

the child’s mind is somehow ‘set’ in a predetermined way to process the sorts of structures which characterize human language … That is not to say that the grammatical system itself is given as innate knowledge, but that the child has innate means of processing information and forming internal structures, and that when these capacities are applied to the speech he hears he succeeds in constructing a grammar of his native language.

(Slobin 1971b: 56)

The crucial point is this: are children wired with prior knowledge about language, as Chomsky has suggested? Or do they come equipped with special techniques for performing linguistic analysis? Are children’s heads loaded with information? Or with puzzle-solving equipment? Are we dealing with a ‘Content Cuthbert’ or a ‘Process Peggy’?

In both the content and process approaches the child may end up with the same type of grammar. But in the second case it is the

result

of analytic procedures. Information was not there at the beginning.

Because the end result may be the same in both cases, it is sometimes claimed that the two points of view are virtually indistinguishable, and should be regarded as two sides of one coin. But there is a crucial difference. Chomsky’s content approach presupposes that the pre-wired knowledge is specific to language, and is independent of general intelligence. But the process approach comes in two versions, an intelligent Peggy and a linguistic Peggy. In the intelligent version, Peggy makes use of the same general cognitive abilities as she

would to cope with everything else she comes across in the world. In the linguistic version, her processing mechanisms are geared specifically to language. So are we dealing with a Content Cuthbert? an intelligent Process Peggy? or a linguistic Process Peggy? We shall consider each of these possibilities in turn.

DOES CONTENT CUTHBERT EXIST?

If Chomsky was correct, then we would expect to find evidence for Content Cuthbert displayed in at least two ways. First, children would be aware of universal constraints. They could never utter a sentence that would be an impossible one for human languages. Second, they would take dramatic steps forward as they ‘set switches’ (

Chapter 5

). Let us see if either of these things happen.

Let us begin with universal constraints. If children are aware of these, then anything quite weird will be ruled out by ‘a biological mandate against wild grammars’ (Goodluck 1986: 55). This ensures that ‘each developing grammar will fall within the bounds of adult language systems as characterized by linguistic theory’ (Goodluck 1986: 64).

So do children always obey universal constraints? This might seem a strange question to ask. After all, adults don’t produce strange sentences such as:

*WHICH PIG ANGELA KNOWS WHO HAS STOLEN? (p. 92.)

Surely, therefore, we are quite unlikely to find equally odd sentences in child language?

Surprisingly, perhaps, a 3-year old boy called Seth has produced a series of ‘forbidden’ utterances (Wilson and Peters 1988). Consider the following:

| Seth | WE’RE GONNA LOOK AT SOME HOUSES WITH JOHNNIE. |

| WHAT ARE WE GONNA LOOK FOR SOME? | |

| WHAT ARE WE GONNA LOOK FOR SOME WITH JOHNNIE? |

Seth appears to have picked on the phrase SOME HOUSES. He has then replaced HOUSES with the word WHAT, and brought this WH-word to the front, but left the word SOME behind. Supposedly, (according to Chomsky) children should know automatically that it is impossible to split up a phrase such as SOME HOUSES, and move half of it away. And this was not an isolated example, so cannot be attributed to a chance mistake. This ‘prohibited’ construction occurred several times, as when Seth was sorting through magnetic letters:

| Seth | IS THIS A FUNNY T? |

| Father | NO, THAT’S A FUNNY I. |

| Seth (holding up another) | WHAT IS THIS A FUNNY, DAD? |

A possible reason for Seth’s extraordinary behaviour is that he is partially blind. Because of this, his father often asked him to finish off sentences, as when playing with the magnetic letters:

| Father | THAT’S A … | Father | THAT’S A NICE … |

| Seth | ALEPH | Seth | OTHER KAF. |

So Seth may have assumed that it was necessary to have a word following the verb at the end of a sentence. At the same time, he knew that WH-words had to go to the front.When he combined these two ‘rules of thumb’, he produced the ‘impossible’ sentences.

Seth ended up chopping the strange sentences out of his speech, so they were only a small detour on the way to fluent English. But Seth’s case suggests that children are not pre-wired with absolute information about language universals from the beginning. They may need to get there gradually, especially if they are in any way disadvantaged, as Seth was.

The gradual acquisition of (presumed) universal constraints is supported by another study, which looked at them from the point of view of comprehension.

One American linguist set out to discover how children understand sentences involving the phrase EACH OTHER (Matthei 1981). Now if you have a sentence such as:

THE BOYS WANTED THE GIRLS TO LIKE EACH OTHER.

the only possible interpretation is that each girl should like all the other girls. Any other interpretation, according to Chomsky, would go against universal constraints. So a number of children between the ages of 4 and 6 were presented with sentences such as:

THE CHICKENS SAID THAT THE PIGS TICKLED EACH OTHER.

They were asked to perform the actions described with farmyard animals. Unfortunately for Chomsky, most of them seemed quite unaware of the proposed constraints. The majority interpreted the sentence as if the chickens and pigs were tickling one another, though a few made the chickens tickle one another. In fact, it has been repeatedly shown that young children often do not pay attention to the syntax, and either answer at random, or utilize a ‘probable world strategy’, that is, interpret sentences by arranging the words to give the most plausible meaning (Cromer 1976).

Of course, one can always argue that the child really ‘knew’ about the constraint, but failed to reveal this knowledge. Perhaps the experiment was badly designed, or the youngsters did not fully understand what they

had been asked to do. Or perhaps the children were simply ‘overloaded’, in that they had been asked to cope with too many things at once. A child forced to deal simultaneously with language and non-verbal responses might appear less competent than he or she really is (Hamburger and Crain 1984).

But the most plausible conclusion is that children do not have any firm, fixed beliefs about language as they acquire it. So far, they do not seem to know what to look for, or what to avoid – though some of this knowledge clearly develops over the course of time. Let us now consider Chomsky’s later ‘switch-setting’ views.

DO CHILDREN ‘SET SWITCHES’?

Universal Grammar (UG) is partly like a switchboard with its switches in neutral position, according to Chomsky (

Chapter 5

). Children know in advance about the possible routes which languages can take. But they have to find out which particular option has been selected by the language they are learning. Once they discover this, they flick each switch, and ‘the system functions’. Is this true?