The Articulate Mammal (30 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

The child may therefore realize that the ‘slot’ a word occupies in the sentence matters more than its strict correlation with an action or event in the external world. At this point, the child has acquired a linguistic category, that of verb.

To take a slightly different example, children may notice that different semantic relationships have some underlying structural similarity:

BLUE SOCK ‘It’s a blue sock’ (ATTRIBUTE + OBJECT).

MUMMY SOCK ‘It’s mummy’s sock’ (POSSESSOR + OBJECT).

They may notice that both BLUE and MUMMY fall into the same slot, the one in front of SOCK, and combine them in their minds. Once two different types of word have been combined under one heading, this is syntax, not meaning.

To summarize, a possible way of moving from a semantic grammar to a syntactic (linguistic) one is to discover that there is not necessarily a direct correlation between types of word and the world. The child therefore discovers abstract relationships underlying the semantic ones. This is the beginning of syntax. Just as some children have a ‘naming-insight’ which triggers a surge forward in vocabulary (

Chapter 6

), so some children may acquire a syntactic insight, which triggers an innate processing device.

Children cannot persist in using meaning to guide them, because language just does not correlate sufficiently with the world around. If children carried on classifying verbs as actions, they would probably make strange overgeneralizations such as:

SHE IS NOISYING.

SHE IS BUSYING.

They would wrongly assume that NOISY and BUSY were verbs, because they describe actions. Similarly, they would fail to recognize words such as LIKE, HATE, GOT as verbs, because they do not involve an action. But children do not seem to have this type of problem (Maratsos 1982).

Somehow, children are specially pre-programmed to notice linguistic regularities, and to give them priority over semantic ones, as shown by children

learning French or German (Maratsos 1982). A language such as French has a somewhat odd gender system (by English standards), since every word has to be labelled as masculine or feminine. Sometimes this correlates with natural gender: UN GARÇON ‘a boy’ (m.), UNE DAME ‘a lady’ (f.), but at other times it does not, as in UN CANIF ‘a knife’ (m.), UNE FOURCHETTE ‘a fork’ (f.). Certain word endings (such as -IEN) are typically masculine, while others (such as -IENNE) are typically feminine. Children pay more attention to this type of information than to matching up gender with the external world. This was demonstrated by an ingenious experiment (Karmiloff-Smith 1979).

The researcher showed children a picture of two little boys, and told them: ‘Here are two FORSIENNES.’ She then showed them another picture, which had just one of the little boys in it, and asked: ‘What’s this?’ The children replied: ‘It’s UNE FORSIENNE.’ They automatically used the feminine UNE ‘a’ because this goes with the ending -IENNE. They did not seem bothered that a boy seemed to be assigned to the feminine gender. If they had required language to correlate closely with the world, they should have been puzzled. But they were not. We conclude that linguistic consistency matters more than language–world matching.

OPERATING PRINCIPLES

Children are wired, the linguist Noam Chomsky has argued, with a substantial amount of innate knowledge (

Chapter 5

). Others have argued that children are simply efficient at sorting out and learning the patterns of any language to which they are exposed. (Tomasello 2003). Let us explore the matter further.

Dan Slobin of the University of California at Berkeley worked on this problem for a number of years, and is regarded as a pioneer in this field. (Slobin 1973, 1982, 1986a–1997b). He started by claiming to have isolated a number of ‘operating principles’ used by children as they process language. Children find certain types of constructions easier to cope with than others. They begin by acquiring ‘easy’ constructions, and will then move on to more difficult ones. This commonsense assumption underlies Slobin’s pioneering work. We need therefore to find out what constitutes ‘difficulty’ for a child in linguistic terms. We can learn a certain amount by simply looking at constructions which are acquired early, and seeing what they have in common, after, of course, checking that the frequency of use by adults is not a major factor for the construction in question. For example, children acquire relative clauses (clauses introduced by relative pronouns such as WHO, WHICH, THAT) in a certain order. They produce relative clauses which follow the main clause such as:

MUNGO SAW AN OCTOPUS [WHICH HAD 20 LEGS]

before ones which are placed inside the main clause:

THE OCTOPUS [WHICH HAD 20 LEGS] ESCAPED

even though there seems to be little difference in the frequency with which adults produce these two types. We can also draw certain conclusions from looking at children’s errors: why, for example, do children so often leave out the auxiliary verb, as in DADDY (IS) SWIMMING, MUMMY (IS) COOKING? However, the best way of discovering which constructions children find easy, and which difficult, he suggested, may be the study of children speaking different languages, and in particular, bilingual children

Slobin pointed out that children who grow up learning two languages do not normally acquire a particular construction simultaneously in both languages. For example, children who are acquiring Hungarian and Serbo-Croatian as twin native languages use Hungarian locatives (INTO THE BOX, ON THE TABLE) long before they produce the equivalent Serbo-Croatian ones. Clearly, there cannot be any conceptual difficulty connected with the notion of locative, because the Hungarian ones are used in the correct circumstances. We conclude that there must be something intrinsically difficult about Serbo-Croatian locatives from the linguistic point of view.

Let us examine the locatives in these two languages, and then go on to consider Slobin’s conclusions (which were based on far more evidence than can be considered here).

The Hungarian locative, on the one hand, is formed by means of a suffix attached to a noun. Each locative expression, INTO, ON, and so on, is a single unambiguous syllable, placed after a noun:

HAJÓBAN ‘Boat-in, in the boat’

HAJÓBÓL ‘Boat-out-of, (getting) out of the boat’.

The Serbo-Croatian locatives, on the other hand, are not nearly as clear cut. The Serbo-Croatian word U can mean either ‘into’ or ‘in’. You can tell the difference between the two uses of Serbo-Croatian U by looking at the end of the following noun:

U KUCU ‘into the house’

U KUCI ‘in the house’.

But the situation is further complicated because the noun endings are not used only in conjunction with this preposition, but have other uses as well. Worse still, another preposition, K ‘towards’, which you might expect to be followed by the same suffix as U ‘into’, in fact takes a quite different noun

ending. So in Serbo-Croatian we find the same prepositional form with more than one meaning, and followed by more than one noun ending. And we find prepositions with similar meanings followed by different noun endings, as well as the same noun endings used for a variety of purposes. No wonder the children get confused!

Slobin concluded that children find some constructions easy to learn and others difficult because they have certain expectations about language. They expect language to be consistent, and assume that there will be one unit of form to match each unit of meaning. They expect words to be systematically modified, especially by means of endings. They assume that word-order is important. They are puzzled by interruptions and rearrangements of linguistic units.

Slobin expresses these expectations as a set of ‘operating principles’ – self instructions which the child might subconsciously give himself as he attempts to analyse linguistic data. For example:

1 allot one form only to each unit of meaning;

2 pay attention to the ends of words;

3 pay attention to the order of words;

4 avoid interruptions.

Of course, Slobin’s list contains many more principles than the four listed above (which appear in a slightly different form in his more recent work). But there is considerable evidence to support his point of view, particularly in respect of the four principles mentioned here. Let us briefly comment on each, giving some examples.

The principle of one form per unit of meaning seems to persist right through the acquisition period. It lies behind children’s overgeneralizations. Once a child has correctly identified the plural ending on words such as DUCKS, COWS, HORSES, he naturally assumes that this ending can be extended to other words, as in SHEEPS, MOUSES, GOOSES. Children confidently expect the same plural ending to be applicable everywhere (with minor phonetic variations). Several researchers have noted that children show an inbuilt resistance to using two different forms to mean the same thing (e.g. MacWhinney 1978; Clark 1987). Conversely, children do not like to allot more than one meaning to any word or word-ending. Karmiloff-Smith (1979) has shown that this principle is still at work in children between the ages of 5 and 8. In a study of the acquisition of the articles LE/LA ‘the’ and UN/UNE ‘a’ in French, she noted that until around the age of 8 ‘the child does not place on one word the burden of conveying more than one meaning’ (Karmiloff-Smith 1979: 224). For example, French UN/UNE can either mean ‘a’ or ‘one’. When children first became aware of the double meaning, several of them in her

experiments tried to invent ways of distinguishing between the two meanings, by altering the syntax. In the following conversation, an 8-year-old correctly says UNE BROSSE for ‘a brush’, but incorrectly uses the phrase UNE DE BROSSE for ‘one brush’. The experimenter had shown the child a picture of a boy in a room with three brushes, and a girl in a room with one brush, and had asked: ‘To whom would I say, lend me a brush?’ The child replied:

… it’s the boy because he’s got a brush (UNE BROSSE), no it’s the girl because she has one brush (UNE DE BROSSE) … no, the boy because he could give you any of his brushes.

(Karmiloff-Smith 1979)

The second operating principle mentioned above, ‘Pay attention to the ends of words’ seems to be subconsciously followed even when children are not dealing with specific inflectional endings. When English children confuse two different words, they often get the last part right: THE LION AND THE LEPRECHAUN instead of ‘the lion and the unicorn’, ICE CREAM TOILET, for ‘ice cream cornet’ (Aitchison and Straf 1981). And it is well known that children tend to omit or confuse the first syllable of a word, particularly if it is unstressed, as in RITTACK, RIDUCTOR, RIFECTION for ‘attack’, ‘conductor’, ‘infection’ (Smith 1973: 12). But this is not only because the syllable is unstressed. It is also because the syllable occurs at the beginning of the word. In Czech, where initial syllables are stressed, it is the unstressed final syllables which are better remembered by children, according to one researcher (Pasčová 1968, reported in Slobin 1973). And further evidence that suffixes are more salient than prefixes or items placed in front of a word comes from the observataion that English children omit prepositions that are essential to the sentence (e.g. MUMMY GARDEN) at a time when they have already started using the correct endings on words (e.g. DADDY SINGING).

The third operating principle ‘Pay attention to the order of words’ is illustrated by the consistency with which children preserve the adult word order in English (

Chapter 6

), while their resistance to alterations in the ‘normal’ order is shown by their tendency to acquire the process of noun-auxiliary inversion relatively late. As we noted, children produce sentences such as WHERE DADDY HAS GONE? before the correct, inverted form WHERE HAS DADDY GONE?

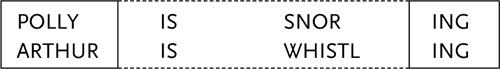

Finally, the principle ‘Avoid interruptions’ is shown by the development of the verbal construction known as the progressive. This describes an ongoing action:

POLLY IS SNORING.

ARTHUR IS WHISTLING.

It is a discontinuous sandwich-like construction because the progressive sequence IS … ING is interrupted by the verb:

It is clear that IS … ING functions as a single unit, because when an ongoing action is described we do not find one without the other. English does not have sentences such as:

*POLLY IS SNORE.

*ARTHUR WHISTLING.

The Harvard children, Adam, Eve and Sarah all used the -ING part of the progressive early (Brown 1973). Both Adam and Eve acquired it earlier than any other ending. But they all omitted the IS (AM, ARE, etc.) part: