The Atlantic and Its Enemies (48 page)

42. and 43.

The men who made Thatcher.

General Galtieri (

centre

) with Admiral Lambruschini (

left

) and Brigadier General Graffigna, Buenos Aires cathedral, May 1980; Arthur Scargill, Orgreave colliery, May 1984

44. and 45.

Couples.

Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, June 1984; Nicolae and Elena Ceauşescu with folkloric Romanian children,

c

. 1985

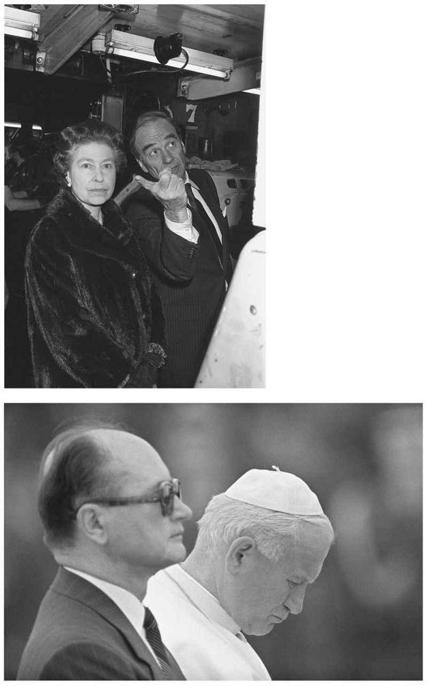

46. and 47.

More couples.

Elizabeth II and Rupert Murdoch, Wapping, February 1985; General Wojciech Jaruzelski and Pope John Paul II, Warsaw, June 1987

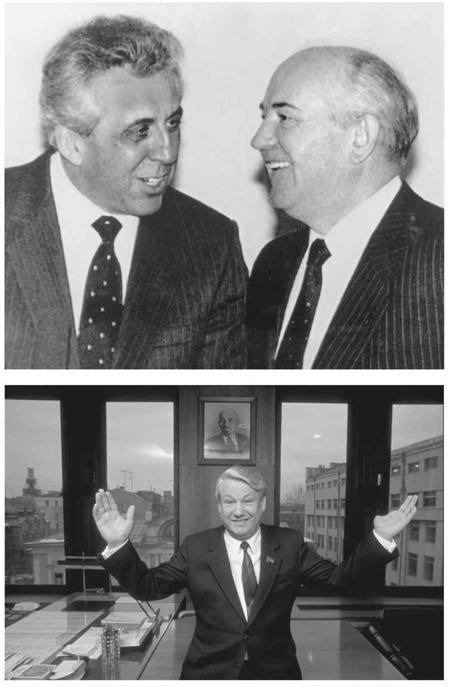

48. and 49.

Cold War spin-offs.

President Mohammed Najibullah meeting Soviet troops, Kabul, October 1986; Prime Minister Turgut Özal meeting Ronald Reagan, April 1985

50. and 51.

The end.

The East German leader Egon Krenz about to lose his job, with Mikhail Gorbachev, Moscow, November 1989; Boris Yeltsin earlier in the same year

It was of course a racial matter. Crime was associated substantially with non-whites, including the Puerto Ricans. Jonathan Reider, in his well-known study of the white backlash in Canarsie, Brooklyn, said that his interlocutors ‘spoke about crime with more unanimity than they achieved on any other subject, and they spoke often and forcefully . . . one police officer explained that he earned his living by getting mugged. On his roving beat he had been mugged hundreds of times in five years.’ In a notorious case in 1972 the police chief ordered all white policemen away from a hospital, when he gave in to the black rabble-rousing politicians Louis Farrakhan and Charles Rangel rushing in to defend criminals who had killed a policeman.

The crisis of 1973 wrecked the city’s finances, as stock exchange dealings fell, whereas welfare costs remained fixed. New York City was only narrowly saved from collapse in 1974, though Lindsay himself had by then given up, and in the later 1970s ordinary city services often came apart - snow not shifted; in 1977 a power failure that lasted for almost thirty hours, during which there was a great deal of looting. As was said, the cheerful city of

Breakfast at Tiffany’s

turned into the bleak battleground of

Midnight Cowboy.

Around this time, too, came a further extraordinary flouting of ancient rules: the release of mental patients onto the streets, as asylums were closed. Progressive-minded specialists had urged this, and New York acquired a sort of black-humour chorus to its problems. And so any American big city had the horrible sight of mentally ill people roaming the streets and combing through the rubbish. Much of this went back to sixties bestsellers, whether Michel Foucault’s

Madness and Civilization

(1965) or Thomas Szasz’s book of 1961,

The Myth of Mental Illness

, and it was the judges who ruled that this had something to do with human rights. The overall sense of these works - Laing’s the best-known - was to the effect that madness was, in this world, a sane response, and there was something to be said for this view. Much the same happened as regards crime. Progressive-minded criminologists had been arguing quite successfully for non-use of prison, but crime rates doubled in the 1960s whereas the numbers in prison actually fell, from 210,000 to 195,000 (by 1990 they had risen again, to one million), in accordance with modish behaviouralist ideas, and in the later 1970s, although there were 40 million serious crimes every year, only 142,000 criminals were imprisoned. The National Rifle Association membership grew from 600,000 in 1964 to 2 million in 1981. If the police and the courts would not defend Americans, what else were they supposed to do?

Contempt for ordinary Americans also showed in the interpretation of the desegregation laws. The worst cases happened over school segregation. Boston schools that served poor districts were dictated to by judges who unashamedly sent their own children to private schools. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had expressly stated that there would be no enforced bussing of children from one district to another to keep racial quotas. But the Office of Education in the Department of Health, Education and Welfare issued regulations in defiance of this. The argument was that if there were not sufficient white children, then segregation must be occurring. The courts backed this in 1972. Almost no-one actually wanted the bussing, but it went ahead, with riots and mayhem, and there was a move out of town, and a rise in private-school enrolment (from one ninth to one eighth). In the north-east racial isolation became worse than before - 67 per cent of black pupils were in black-majority schools in 1968 and 80 per cent in 1980 (more than even in 1954). There were horrible stories at South Boston High, where black children were exempted from fire drills out of fear for their safety if they left the building. A journalist, J. A. Lukas, wrote the classic book on the story, all the more gruesome because the grand liberals did not have to have anything directly to do with their handiwork. Michael Dukakis lived in a decent suburb and sent his children to private school; Edward Kennedy used St Alban’s School, and the liberal journalists of Ben Bradlee’s

Washington Post

did likewise.

Where was American democracy? Law was passed by an apparent ‘Iron Triangle’ of lobbyists, bureaucrats and tiny subcommittees. The Democrats (now essentially controlled from the north-east) reformed the House in such a way as to remove the old men from committee chairmanships, as from October 1974, when one of them became involved in a sex scandal involving a whore. The old system had been able to deliver votes, for instance for the Marshall Plan, but it could also be used to stop left-Democrat aims because experienced chairmen knew how to do it. A San Francisco congressman, Phil Burton - he supported Pol Pot in Cambodia, in 1976 - was backed by labour, but the result, with many now open committees, was that lobbyists flourished, and the small print of enormous legislative documents contained provisions to satisfy them, quite often unnoticed by scrutineers. It became impossible to get the budget in on time, and there had to be endless ‘Continuing Resolutions’ which simply enabled the government to go on spending as before: in 1974, $30bn more; between 1974 and 1980 spending (beyond defence) rose from $174bn to $444bn.

It was not surprising that so many Americans felt hostile to the whole process, and a radical, Christopher Lasch, wrote powerfully as to how a bureaucracy-dominating elite had taken power from people to run their own lives. He particularly despised the endless fuss made about cigarette-smoking - it started with a ban in Arizona, in 1973, on smoking in public buildings - but this was a frivolous period, the landmarks down. What Leszek Kołakowski called the politics of infantilism went ahead. Alvin Toffler pronounced in 1970 that the future would amount to endless leisure. For some, it did. In 1970, 1.5 million drew a disability pension, but 3 million in 1980; one tenth of the nation’s families was headed by a single woman, living on welfare. Paul Ehrlich in 1968 looked at

The Population Bomb

and asserted that there would be famine in the 1970s, and thought that pets should be killed, to save resources. One man made his name in the seventies with the claim that there would be a new Ice Age, and made his name again twenty years later with a further claim that global warming would mean apocalyptic floods. The wilder shores of the sexual revolution were explored, Niall Ferguson remarking that the only people who wanted to join the army were women, and the only people who wanted to get married were gays. Feminism, a cause that went back to hesitant beginnings under Kennedy, was vigorously promoted through the courts, and quotas for ‘positive discrimination’ were allowed - although Congress had never voted for this. Equality was applied, with many absurdities resulting (Edward Luttwak got himself off guest lists when he pointed out that heavy military lorries, driven by women, might crash because the driver’s legs were not strong enough for the controls). In Ohio women were at last ‘allowed’ to lift weights heavier than 25 pounds; in February 1972 the ghastly little word ‘Ms’ was allowed in government documents; women were ‘allowed’ to enter sports teams’ locker rooms; in New York women were permitted to become firemen; and in 1978 women were allowed to serve on naval vessels, ten of the first fifty-five becoming pregnant. Here was America at its witches-of-Salem weirdest.

The economy itself was losing the lead that it had had over all others, and, again, inflation had much to do with this. Unions, on the whole, could resist it, at least in the big industrial firms, where blue-collar wages kept up. Labour was all-important for the Democrats, and AFL-CIO grew, up to 1978, as ‘corporatism’ prevailed, but it was increasingly not so much blue-collar workers as soft-professional teachers in the lead. There were alarms as to the competitiveness of American industry. Kenneth Hopper, a Harvard Scottish warhorse, noted (‘American Machinist Special Report’ of July 1970) that output per hour in factories had increased by 20.1 per cent between 1961 and 1965, but by less than half of this figure in the following five years; the growth in take-home earnings fell from 23 per cent to −1.5. The point was that ‘of the major nations of the world, the US reinvests the lowest proportion of its GNP’ - 16.6 per cent as against 23 per cent in Germany and somewhat more in France, or 34 per cent in Japan, such investment including machinery and housing. In engineering, from the mid-fifties onwards, investment was far lower, per $1,000 deliveries, than in Europe or Japan (about $12 as against $60-80), and fixed assets were even below England’s. There was some official dishonesty involved in defence of this: a strange myth was propagated by the OECD that American equipment was only four to five years old, that investment had really been quite adequate, that overinvestment needed to be taxed. The Department of Commerce knew better. America, or parts of it, had been vastly spoiled and had not had to work; even in 1968 some essential structures were over fourteen years old. Congress sometimes ascribed the inflation to business’s desire for capital investment, but in fact new equipment was indeed needed, and what had confused the figures was tax. Depreciation allowances were unreal, and old equipment was recorded as relatively recent. There was also much grumbling that Americans had a low propensity to save (6.1 per cent of their income, whereas the German figure was 13 per cent and the Japanese 20 per cent). But only a fool would have saved in countries where inflation ran in double figures and interest rates in single (or, after tax, half of these).