The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution (25 page)

Read The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution Online

Authors: Tom Acitelli

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

*

The rest of the list was mostly imports as well as a few regional brewers like Weinhard's and Rainier.

*

Moon and his friend, Scott Chisholm, were both partly of Native American descent. Chisholm died in 2007.

San Francisco | 1986-1987

T

he call could not have come

at a worse time for Pete Slosberg. It was Bob Stoddard on the line; Stoddard had taken over Palo Alto Brewing in Mountain View, California, from father-and-son founders Kenneth and Jeffrey Kolence. Now, at the beginning of 1987, it was going out of business in a rather messy way. Stoddard told Slosberg, who was brewing his first batches of beer under contract there, that he was going into Chapter Seven bankruptcy. It was a Wednesday evening; the sheriff would arrive on Monday to lock the brewery's doors; everything inside would be off-limits. Slosberg and his business partner, Mark Bronder, had to get their beer bottled and out the door before then.

It was Bronder who had suggested they start a business. An Omaha native who grew up in Minneapolis and Nashville as the son of Johnny Carson's onetime radio partner (his dad later became an advertising executive), Bronder had an MBA from Northwestern and had logged time in IT for a steel firm in Chicago. He left that job when he realized the managers had all been there for a decade or moreâand were still managers. He went to consulting powerhouse Booz Allen and then was lured by the glam of Silicon Valley. The parking lot outside of ROLM was studded with Porsches and Ferraris. You didn't have to wear a tie in the officeâyou could even grow a beard, like his nearby cubicle neighbor, Pete Slosberg. The unfailingly gregarious Bronder and the slightly reserved Slosberg became friends. One Friday, Bronder asked Slosberg what he was doing over the weekend. Slosberg told him he was competing in a homebrewing contest. Bronder wished him luck in that half-listening

workplace wayâand promptly asked him on Monday what he had done over the weekend. Slosberg reminded him about the homebrewing competition.

“How'd you do?”

“I came in third,” Slosberg replied.

“Well, that's pretty good,” Bronder said like the Little League coach of a losing team. “How many people entered?”

“Five hundred. It was statewide.”

Five hundred, Bronder thought, and you placed third! Bronder was not a beer drinkerâhe had not had a drink in his lifeâbut he realized Slosberg's homebrew must be pretty good. Bronder, who would leave ROLM to go into venture capital, pitched the idea of going into business together beforeâand duringâSlosberg's twelve-week sabbatical from ROLM. The sabbatical allowed him to travel widely, including in South America. He and his wife and their two children crossed the Andes from Argentina to Chile; they spent spells in Peru and Bolivia; Slosberg sat atop a mountain overlooking Machu Picchu, Andean pipes playing about him, and knew he could not go back to ROLM when he returned to the Bay Area. He reached out to Bronderâhe was in. The pair began brainstorming for business ideas.

They knew of the craft beer movement. It was Northern California in 1985âyou couldn't miss it. Fritz Maytag's twenty-one-person operation on Mariposa Street in San Francisco was still the largest craft brewery in the United States, with forty thousand barrels of six different types of beer annually. Ken Grossman's Sierra Nevada out of Chico was brewing more than ten thousand barrels annually, mostly of its flagship pale ale, which was becoming the archetype for not only hoppy West Coast beers but also for the American interpretation of the English-born style. And there were the Bay Area's vaunted brewpubs, like the Mendocino Brewing Company in Hopland and Buffalo Bill's in Hayward, the second and third oldest in the nation (Bert Grant's original brewpub, in Yakima, Washington, was up to three thousand barrels annually). There were by 1986 as many as twenty-six craft breweries, including brewpubs, touching every region of the nation, save for the Deep South and Hawaii (and those were not far behind). And for every one that closed, as we've noted, there seemed to be another ready to start up in its place. Still, distribution for most remained severely limited, often to the immediate vicinities; and the production, even aggregated, paled next to Big Beer's output. Anheuser-Busch on its own was producing more than sixty million barrels a year.

It helped, then, that Slosberg and Bronder were dreaming in the Bay Area, where American craft beer was born and where it was in relative abundance. Had they been in, say, Rochester, New York, Slosberg's old home, or even in

New York City, where he went to college and graduate school, it's entirely possible their entrepreneurial itch would have been scratched by an entirely different industry. As it was, the pair settled upon craft beerâit was a growing industry, especially where they were; it looked fun; and, besides, Slosberg was a good homebrewer with a beer-can-collecting habit that often meant sudden stops on family vacations. Plus, Bronder's ad-man father had taught him that creativity could make a difference, that a little company could break through with just the right angle and amount of fun. Bronder more than anything wanted to have fun with the advertising.

They examined the economics and, like Matthew Reich in New York and Jim Koch in Boston, decided on contract brewing. Enter Bob Stoddard, a local sales rep for Miller who bought the Palo Alto Brewing Company in 1985 from the Kolences, when its annual production was about fifteen hundred barrels with a seven-barrel system. The Mountain View brewery was near Slosberg's house, and Stoddard's expansion to a twenty-barrel brewhouse with an old soda-bottling line spawned enough excess capacity for Slosberg and Bronder's first batches. Away went much of the start-up costsâthe pair raised an initial $21,000 and incorporated what they called Pete's Brewing Company on April 23, 1986. They got the necessary licenses only after resistance from the state, which initially balked at allowing the company to make its commercial beer using someone else's equipment.

The first beer brewed late that year in Stoddard's kettles came from a recipe Slosberg stumbled upon trying to imitate Samuel Smith's Nut Brown Ale. Deep brown, with a nutty finish and brewed by the oldest brewery in Yorkshire, it was first introduced to the United States by Charles Finkel's Merchant du Vin importing company in 1978. Slosberg's fourth attempt at a suitable knockoff eight years later instead produced a brown ale with a reddish color and a bitterer taste. He and Bronder eschewed calling it Pete's Brown Ale or, simply, Pete's Aleâwhat was memorable about either? They wanted something zippier for the increasingly crowded beer shelves of the Bay Area (the region was a hub not only of the growing craft beer movement but for imports, too, which were enjoying their briskest growth since Prohibition). Then Bronder heard a bit on San Francisco radio by comedian Bobcat Goldthwait, who threw around the adjective “wicked”â”wicked” this and “wicked” that. Slosberg liked it, too, and they slapped it in between “Pete's” and “Ale.” Bronder got the graphic designer who did the brochures at his venture-capital firm to mock up some packaging and paraphernalia with pictures of Slosberg and his white-and-black bull terrier named Millie. The designer didn't care for Slosberg's mugâ”The dog's a kick,” she told Bronder. Millie became the face of Pete's Wicked Ale.

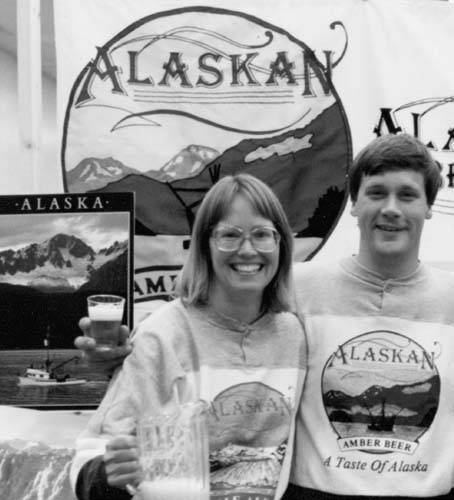

Pete Slosberg in front of the very first case display of Pete's Wicked Ale, at the Liquor Barn in Mountain View, California, in 1986. His English terrier can be seen on the packaging.

COURTESY OF PETE SLOSBERG

Slosberg and Bronder got that endangered batch out of the doomed Palo Alto Brewing Company with more than a little help from their friends. Beer and pizza powered a two-and-a-half-day, round-the-clock bottling, labeling, and packaging spree that produced another couple of hundred cases of beer to join the first ones at Bay Area retailers, produced months earlier by Stoddard without a hitch.

The narrow escape revealed a problem with contract brewing. Six craft breweries had come and gone in the past ten years: New Albion, DeBakker, Cartwright, Real Ale, River City, and now in early 1987, on its second owner, Palo Alto. Meanwhile, more of the larger regional breweries continued to succumb to the industry's consolidation. Miller, in a perfect example of both the targets and the goals of this consolidation by the 1980s, bought the 120-year-old, family-owned Jacob Leinenkugel Brewing Company in Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin (population 13,108), around the same time Palo Alto went bankrupt. Why? Leinie's, as locals called it, produced sixty-one thousand barrels annually to Miller's 38.7 million. No matter: Miller wasn't after size; its executives said it wanted the regional simply to reach those Leinie drinkers who would never pick up a Big Beer brand. The sweeping consolidation of the past thirty years had given way to one of attrition. Bit by isolated bit, Big Beer was going after the last vestiges of independent breweries, to the point where analysts could now speculate there would be only a few breweries in the entire country by the new century. Craft brewing was barely on anyone's radar, perhaps less than 2 percent of the beer bought in the United States (who was even tracking it?). For contract craft brewers, this meant fewer and fewer hands controlled the physical breweries that remained; and not all were amenable to contract brewing, excess capacity or not. It would take Slosberg and Bronder six months to locate another set of kettles and pipes. They found them more than two thousand miles awayâand just in time.

Juneau, AK; Baltimore; Boston | 1985-1986

G

eoff and Marcy Larson

could not have contract brewed had they wanted. The nature of their particular chosen environment, Alaska, did not allow it. The Last Frontier was pretty much that in the early 1980s as far as craft beer wentâor any beer, with European imports often arriving past their freshest dates and craft brands like DeBakker, Sierra Nevada, and Anchor distributive rarities. Shipping distances even within the state could be immense; it was a

day's drive between Juneau, the capital, and Anchorage, the largest city, for instance. A start-up craft brewery was a capital and an organizational hurdle anywhere else in America; add to it this unique crucible of remoteness, and the prospect was positively frigid.

Still, Geoff Larson had taken that turkey run with Fritz Maytag. That meant something, he remembered.

Larson, who sported a Beatle haircut and whose smile seemed to cock to the right, had grown up all over as the son of a foreign-service officer, periodically landing for spells in Washington, DC, before college at the University of Maryland, where he studied chemical engineering. In his last summer before graduation, he decided to hitchhike to Alaska but ran out of money in Montana. He ended up as a short-order cook at Glacier National Park, where he met a blond-haired Maryland native who had just graduated from college with plans to be a photojournalist. To pay the bills, she worked as an auditor for the park. Marcy's and Geoff's schedules lined upâshe worked nights, he worked mornings, and by noon their days were their own. The two became hiking buddies and soon much more. After the summer, Geoff returned to finish his five-year program and Marcy headed to Alaska, to another national park and another auditing job.

Geoff had been into cooking and as a chemical engineering student knew the vagaries of fermentation. He had even joked with college friends about starting a brewery. He tried the mainstream job route for a year after graduation. But something bit, and in 1981, on a trek back to Marcy in Alaska, he found himself on Greyhounds and couches, visiting breweries to soak up information. He visited F. X. Matt II at his eponymous brewery in Utica, New York, and as he would be with Matthew Reich and others, Matt was patient with the young visitor who had written him, showing Larson around and taking him on a further psychological tour of what he thought it meant to be a commercial brewer at that point in America. Matt talked in particular and at length about the shared heritage brewers had. “If you brew beer, you represent the entire industry,” he told Larson. “Brew the best beer you can.”

Larson heard a similar message shortly afterward on a trip west to Anchor on the Wednesday before Thanksgiving. Unbeknownst to Larson, Matt had written Fritz Maytag about him; now it was that brewer's turn to seek out the would-be entrepreneur for an afternoon of mentorship. Maytag then drove Larson to the Greyhound depot, where he would catch a bus to Seattle and a ferry to Juneau. On the way, Maytag stopped to buy his Thanksgiving turkey. It was that kind of industry.