The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution (26 page)

Read The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution Online

Authors: Tom Acitelli

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

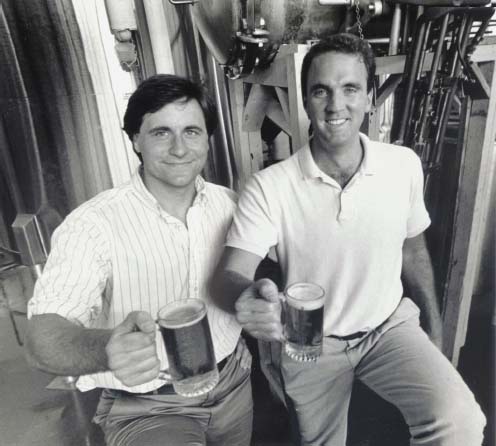

Marcy and Geoff Larson of Alaskan Brewing at a Great American Beer Festival in the early 1990s. The GABF was often the first time a geographically isolated craft brewery like Alaskan got its shot at a wider consumer audience.

COURTESY OF THE ALASKAN BREWING COMPANY

Back in Juneau, the couple got down to gathering investors. The banks all said no way, but after thirteen months Marcy and Geoff ended up accumulating eighty-eight backers from across Alaska. Few were interested so much in craft beer as they were in something new and invigorating in a decidedly bleak economic climate. In 1985, the couple rented from a neighbor two thousand square feet in an unfinished warehouse in an industrial area of Juneau. They were able to get new brewing equipment through JV Northwest, a manufacturer based in Canby, Oregon, that would end up supplying many craft breweries.

Geoff spent two weeks apprenticing at the Millstream regional brewery in Amana, Iowa. Their bottling equipment (they eschewed kegs at first) was secondhand. In total, the Larsons spent $310,000 getting what they called the Alaskan Brewing Company off the ground in 1986. The twenty-eight-year-olds, who married in 1985, held the nation's sixty-seventh brewing license. Even after all the start-up stress, the couple still looked young and effusive enough to pass for college students.

The first 253 cases of their Alaskan Amber that rolled out of the Juneau warehouse with the help of ten volunteers in December were especially important for the wider craft movement for two reasons. First, the amber was a more malty flagship beer than had been seen in a while; only slightly hoppy in taste, it was certainly an anomaly for the West Coast start-ups; that was deliberate on the part of the Larsons. The beer was based on a popular local recipe from the early twentieth century that used Saaz hops from what is now the Czech Republic; the hops were difficult to come by in then-territorial Alaska, and so were used sparingly. Second, the brewery represented a logistical triumph: the first cases distributed outside of Juneau went first by ferry to Haines and then outward via truck. The Larsons' Alaskan Amber was a boundary pusher; it proved that while the craft beer movement was reasserting the importance of geography in American beer, geography did not preclude its conquests. It was a sign of the movement's potential that Alaska clearly would not be its last frontier.

Commercial brewing in any of the great cities of the EastâWashington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and Bostonâwould have been an anomaly as late as the mid-1980s. Washington's last brewery, the Olde Heurich Brewing Company, closed in 1956 and was razed to make room for a national cultural hub on the Potomac that became the Kennedy Center. In Baltimore, the last brewery behind the apropos American Beer brand closed in 1973, leaving vacant a gorgeous eleven-story building dating from 1887. As we've seen with New York, Brooklyn alone had dozens of breweries by the turn of the last century. And in Philadelphia there may have been hundreds, big and small, in operation at any one time in the 1800s and early 1900s; there was just one left, Christian Schmidt and Sons, though it would close in 1987. Boston, like Baltimore and Washington (and soon Philly) had no commercial brewing presence at mid-decade. The city's last brewery, Haffenreffer in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood, closed in 1964, ending centuries of brewing in Boston. When Carling in Natick closed in 1975, brewing disappeared altogether from Massachusetts,

where it had been woven into the socioeconomic fabric since just after the

Mayflower

finished its voyage from England in 1620.

Then, in the summer of 1986, the Commonwealth Brewing Company opened in Boston's West End, a block from Boston Garden. Its proprietor? Richard Wrigley, the English transplant who had likened Michelob to “a soft drink” and who had opened New York City's first brewpub (the East Coast's, really) in the fall of 1984. As with his Manhattan Brewing Company, Wrigley saw the Commonwealth Brewing Company's mission as one servicing “serious beer drinkers,” some of whom were not alive when Boston lost its last commercial brewery. Along with a seasonal with ginger in it, the pub planned to brew five beers regularlyâa golden ale, an amber ale, a porter, a stout, and what Wrigley dubbed Boston's Best Burton Bitterâin the basement, with bar food, including smoked meats and fish, served upstairs. The beer selections were likely to find a thirsty audience. As a

Boston Globe

article on the brewpub's opening noted, “Wrigley isn't the only successful Boston brewer.” Taking cues from the Maltose Falcons and other, older West Coast homebrewing clubs as well as from the personal computer age, Boston's two-year-old Wort Processors had won an award at the American Homebrewers Association's latest national competition. Moreover, Jim Koch and Rhonda Kallman were growing the Boston Beer Company well beyond those original thirty accounts they needed to launch. Boston, among the great cities of the East, seemed poised for the biggest craft beer renaissance.

Rich Doyle, Dan Kenary, and George Ligeti certainly hoped so. On August 12, 1982, the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped to what would turn out to be a recession low of 776.92. It had nowhere to go except up: the bull market run of the 1980s was snorting and pawing at the gate. The three young men, all Harvard graduates, could stand to make a financial killing. All had already started down particularly lucrative roads: Ligeti worked in oil and gas, Kenary as a corporate lending officer, and Doyle in New York at the precursor to the financial services firm Lehman Brothers. But they pivoted. Doyle went back to Harvard to earn his MBA, and to avoid more class time he signed on for an independent study project that involved drawing up a business plan. He chose beer. Like fellow Harvard MBA Jim Koch around the same time, he had read an article on Fritz Maytag, and he had heard about Bill Owens's Buffalo Bill's brewpub in Hayward, California. Doyle had also traveled in Europe and to other parts of the worldâeven working for a spell as a bartender in New Zealandâand had discovered the pleasures and poignancies of locally produced beers. Why couldn't the beers he and his buddies drank in the Boston area also be locally produced? Killian's Irish Red, the Coors stab at a red ale

introduced at the Great American Beer Festival in 1982, was perhaps the most exotic thing going in the area. With his roommate and through the independent study, Doyle began drawing up a business plan for a start-up brewery in greater Boston.

He enlisted Kenary, a Worcester, Massachusetts, native who had earned an MBA from the University of Chicago and whom Doyle had known since before college; and Ligeti, a Canadian who was also passing through the Harvard program. Part of the plan's research involved visits to craft breweries out west. Kurt and Rob Widmer, clad in coveralls, talked brewing at their Portland, Oregon, operation; so did Richard and Nancy Ponzi in nearby Bridgeport, Connecticut. Paul Shipman of the Independent Ale Brewing Company, brewer of the increasingly popular Redhook Ale, met the visitors in the former transmission shop in Seattle; and Doyle by himself popped in on Mike Hale's brewery farther south in Washington State. At different times, he and Kenary made it northward in the state to visit Thomas Kemper by the Canadian border; and then they went over the border.

Canada had had its own brush with Prohibition. Before and during World War I, provinces and territories in the Great White North began banning alcohol production to some degree, as well as forbidding imports from south of the border and elsewhere. After the war ended in late 1918, provincial and territorial governments began repealing their prohibitive measures, starting with Quebec the following year. Prohibition had left its mark, though, and it would be a generation before Canada had really replaced the hundreds of breweries, wineries, and distilleries it lost. The first Canadian craft breweries began opening in the early 1980s, inspired in part by American ones. Canada did, however, beat America to the first brewpub on the continent. Opened in 1980, two years before Bert Grant's brewpub in Yakima, Washington, John Mitchell and Frank Appleton's Horseshoe Bay Brewery and Roller Inn Pub, on British Columbia's Howe Sound, about thirty miles north of Vancouver, was also the country's first craft brewery. Doyle and Kenary stopped nearby in Victoria at another creation of Mitchell's, Spinnakers Gastro Brewpub and Guesthouses, which opened in May 1984 and which served classic English-style ales from hand-pumped taps.

Doyle, Kenary, and Ligeti were not homebrewersâjust what we would now call beer geeksâso the visits were a technical eye-opener. The plan moved forward, often during brainstorms in Doyle and Ligeti's Watertown, Massachusetts, apartment or at local bars. They set a production goal in their business plan of sixty-five hundred kegs and eight thousand cases annually by year five, with nearly $2 million in revenue. As for the first year, they would be

ecstatic with one hundred draft accounts. In the spring of 1986, the trio began raising funds from family, friends, and friends of friends, eventually amassing $430,000 from thirty-five people. The trio, like the young couple behind Alaskan Brewing, the Larsons, found that beer got an emotional reaction from peopleâa gut feeling, whether they knew much about it or not. That came in part, Doyle, Kenary, and Ligeti realized, from the growing popularity of other foodstuff start-ups that stood athwart the homogeneity of their particular niches. These included Ben & Jerry's, the ice cream brand started by two Vermont hippies in 1978 with $12,000 (one-third of it borrowed), and, of course, Starbucks, then a quirky, almost quaint chain out of Seattle, many years from its hegemony. This was a fresh context in which newcomers could think about craft beerâas another foodstuff that was tastier and created in a more hands-on way, often locally, and therefore costing a little bit more than the bigger brands.

Rich Doyle, left, and Dan Kenary.

COURTESY OF THE MASS

.

BAY BREWING COMPANY

Funding incoming, Doyle called Michael Lewis at UC-Davis. He asked for recommendations for brewmasters. Lewis listed several of his students, and

Doyle headed westward to interview them. He hired twenty-three-year-old Russ Heissner, who had worked at a California winery. They found and fixed up a couple of thousand square feet of warehouse space in an old Navy yard on the South Boston waterfront. It was still the Southie of mobster Whitey Bulger and gang turf wars, a gritty, largely industrial swathe the general public avoided; the city was happy to have the Mass. Bay Brewing Company as a tenant. They bought the kettles from JV Northwest in Oregon and a secondhand soda-bottling line. They also bought a truck to do distribution themselves, as every wholesaler in the area turned them down (“Five thousand cases? Not big enough”). Heissner's first recipe was for what the company called Harpoon Ale, a sweet, citrusy amber. The first two commercial kegs of it, delivered by Doyle and Kenary, were tapped at bars in Beacon Hill and Jamaica Plain on June 2, 1987, a Tuesday. Breweries were back in Boston.

Portland, ME; Abita Springs, LA; St. Paul, MN; Manteo, NC | 1985-1986

D

avid and Karen Geary were,

like the Larsons in Juneau, another husband-and-wife team keen on bringing a craft brewery to a particularly geographically inhospitable place: in this case, Portland, Maine, with its long winters and a population of just over sixty-one thousand in a state still mostly rural. The Pine Tree State's last commercial breweries had closed with Prohibitionâand never came back. In March 1986, longtime homebrewers Hugh Nazor of Georgetown and Jon Bove of South Portland introduced Portland Lager, a recipe they arranged to have contract brewed by the Hibernia Brewing Company in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. It proved popular with locals, even at five dollars or more a six-pack, though not popular enough for investorsâNazor and Bove spent fruitless years trying to raise funds for a brewery for their Maine Coast Brewing.

David Geary's path proved more successful. It all started when the twentieth Laird of Traquair stayed with him in Portland, Maine. Peter Maxwell Stuart had in 1965 revived the brewery at his family's estate, a dictatorially ornate

Scottish castle dating from 1107, complete with a hedge maze and priest holes. Geary knew Stuart's American importer. After a pleasant enough stay in Portland, the laird told Geary that if he ever wanted to learn the brewing trade, he should drop him a lineâStuart would set him up with an unpaid job at the Traquair brewery and give him letters of introduction to other breweries in Britain. Geary did just that after the company he sold medical supplies for went bankrupt, and at thirty-eight he could not stomach the process of sending out résumés. He incorporated the D. L. Geary Brewing Company in October 1983 and then split for Scotland and England for three months. The hours were longâmash would happen around 6 A

M

âbut the lifestyle was beyond quaint for the former salesman from Maine. There was tea at 10, a beer at 11 (in line with the British custom of elevenses), and the camaraderie of craftsmanship. The bearded, blond-haired Geary almost forgot it was a business, as cutthroat in Britain, where the brewing industry was also consolidating, as it was in the New World.