The Audrey of the Outback Collection (26 page)

Read The Audrey of the Outback Collection Online

Authors: Christine Harris

She couldn’t wait to tell Price.

Then she remembered that she couldn’t tell him anything about it. Janet was a secret.

‘But …’ Audrey rubbed at her forehead. ‘You can’t walk. When did you see my house?’

‘Night of the big dust storm.’

‘That’s the night

I

saw the ghost! If we both saw it at the same time, then …’ Audrey stopped. She looked at Janet’s smock. At night, her legs wouldn’t show up, but the pale smock-dress would.

‘

You’re

the ghost.’

‘No!’ Janet shook her head. ‘I’m a girl.’

‘I mean, I reckon I saw

you

.’

‘You saw me?’

‘And you saw

me

.’

‘I only seen you here.’

‘I went out to the dunny on the night of the dust storm,’ explained Audrey. ‘And I was holding up a hurricane lamp. That was the light! You couldn’t see me properly, cos of the dust.’

Janet gave a sheepish grin. ‘You and me, we gonna be friends till our teeth fall out. Even our spirits know each other.’

Audrey smiled at Janet, but it quickly faded. ‘I might not see you again after you go. I don’t know where you live.’

Janet blinked her thick eyelashes. ‘I know

your

place. One day, I’ll come back. First, I have to get out of here and go home.’ Leaning forward, Janet ran her fingers gently over her swollen ankle. ‘This gonna make me slow walkin’.’

‘You’ll get hungry.’

‘All the time, hungry.’

‘Me too,’ said Audrey. ‘You’ll need a bag to carry food. Mum’s got lots of hessian bags. I can get another one and start putting food in there so you can carry it.’

‘And water. I get thirsty when I’m walkin’.’

Just

talking

about doing something made Audrey feel better, and Janet looked more cheerful.

But even while they were talking, the police and a tracker were probably searching for Janet. If Janet’s ankle didn’t heal soon, the men would find her.

Twenty-six

Audrey dropped her pencil and flexed her fingers.

Mum looked up from her sewing.

‘I’ve got prickles in my fingers,’ said Audrey. ‘I’m just stretching them.’

‘That’s all right, dear. Your arithmetic will still be waiting when you’re finished.’

Audrey sighed.

Douglas, playing trains with a small tin on the floor, hiccuped. Then he giggled.

‘Is a hiccup when your teeth are coughing, Everhilda?’ said Audrey.

Price snorted and then pretended that he was coughing instead of laughing.

Mum looked across the table at Audrey. Her expression was both mother

and

teacher. ‘When we’re having lessons, it would be better not to use my first name, dear.’ Her eyes twinkled. ‘I seem to remember a certain young lady wanting to be called Miss Barlow when she tried being teacher.’

‘But that didn’t work.’ Audrey rubbed her hands together. ‘Price was naughty.’

Her brother’s head shot up. ‘I

was

not.’ The end of Price’s pencil was chewed. When he was stuck for answers, he nibbled it.

Douglas hiccuped again.

‘Audrey, you’re not going outside till it’s finished,’ said Mum. ‘The longer you delay and cause distractions, the longer it will take you.’

‘Bloke saw snow when she went to Victoria,’ said Audrey. ‘What

is

snow?’

‘We’re doing numbers today.’

‘I can’t think about numbers cos there’s no room in my head. It keeps wondering about snow. Is snow when clouds shiver?’

‘Well, just pretend the numbers are snowflakes. Then you can add them up.’

Audrey sighed, but gave in and tried to make sense of the numbers on her page. But then she looked up, startled. ‘What’s that noise?’

‘

Audrey!

’ Mum’s eyes widened in warning.

‘Hang on, I can hear something too,’ said Price.

Audrey felt a chill that had nothing to do with snow

or

arithmetic and everything to do with being afraid. She felt frozen in her chair, unable to move, not even to stand up and check what was coming towards the house.

Mum, Price and Audrey turned their heads towards the back of the house. Even Douglas stopped his tin ‘train’ to listen.

Audrey looked towards the window where Stumpy usually stood during lessons. He often stuck his camel head between the curtains and pulled faces to make Audrey giggle. But today, Stumpy wasn’t there. Maybe he was watching over Janet out at the cubby.

‘Is that the mailman back again?’ Mum frowned. ‘He’s not due for two months.’

Price jumped up, rushed to the door and flung it open.

The goats were bleating their heads off, and Nimrod, the big rooster, crowed to show how tough he was.

The sound of a motor became louder.

‘It’s a car!’ shouted Price.

Audrey’s heart leapt. Her chest hurt.

A big black car, covered in red dust, pulled to a stop.

The driver’s door opened.

A man got out.

He wore a peaked hat that shaded his eyes. His shoes were unusually shiny. And his dark jacket had a long row of equally shiny buttons.

Twenty-seven

The policeman sat his cup back in the saucer. ‘That was delicious, Mrs Barlow.’

Audrey’s mum smiled, but it didn’t reach her eyes. She stood with her back to the bench. Usually when there were visitors, she sat with them at the table.

‘More tea?’ asked Mum.

‘I won’t say no. Thank you. It’s camel country out here, a long time between drinks.’ He laughed heartily. His teeth were yellow and higgledy-piggledy although the rest of him was neat, tidy and buttoned.

Mum stepped to the table and picked up the teapot. Her cheeks were red even though the kitchen was cool. She poured strong, brown tea into the policeman’s cup. Her eyes fixed on his jacket buttons, then she raised them to look across at Audrey. Their eyes held. Then Audrey looked aside.

Audrey thought hard. What could she do to warn Janet? Make an excuse to go to her room, then climb out the window and run to the cubby? No, that would look suspicious. The policeman could easily follow her and, with a car, he’d catch up to her in no time at all. He was here in the kitchen, so that meant he hadn’t found Janet yet. But he was close.

Too

close.

Through the open kitchen door, Audrey saw Price run his hand along the car’s bonnet. His fingers left streaks in the dust.

‘Don’t touch the vehicle, young fellow,’ called the policeman. ‘We can’t have any damage. Government property, you know.’

Price snatched back his hand.

Audrey glanced out at the Aboriginal man, who had come with the policeman. The man stood by the car. His wide-brimmed hat was pushed back on his head. He had a small beard that was cut close to his face. He’d rolled up the sleeves of his fawn shirt as far as his elbows. He didn’t have shiny shoes, like the policeman. Instead, he wore pull-on boots that were as dusty as the car. The buckle on his trouser belt was shiny though, and so were his eyes. They looked everywhere, but he hadn’t spoken a word.

Audrey swallowed over a lump in her throat. Her mouth was dry, but she didn’t want to draw attention to herself by asking for a drink.

‘Would your … would the other gentle man like some tea?’ asked Mum.

‘Oh. The tracker?’ said the policeman. ‘Your boy can give him some water outside.’

Mum’s mouth tightened into a straight line. She turned to take another cup from the shelf and filled it with tea from the pot. ‘Audrey, dear, would you take this to the gentleman outside?’

The policeman gave Mum a look that hinted that he wasn’t happy that she’d ignored him.

Audrey looked down as she picked up the cup. From the corner of her eye, she saw the policeman dig out two large spoons of sugar from the bowl for his tea, stir it, then tap his spoon on the cup. He slurped, and then clicked the cup back onto the saucer.

‘Are you

sure

you haven’t seen the girl, Mrs Barlow?’ the policeman asked.

Audrey’s mum shook her head. ‘I haven’t been far from the house lately.’

The policeman stared at Mum’s round tummy. Audrey wanted to tell him not to, but she didn’t dare. That tummy belonged to the family. The baby was theirs. He wasn’t allowed to look.

Mum’s face went even redder. ‘My husband will be home soon.’

‘What about you, child?’

Audrey froze.

He was looking at

her

. Talking to her.

But she couldn’t look at

him

. Her tongue seemed stuck to the roof of her mouth.

‘My daughter has been helping me quite a lot lately,’ said Mum. ‘Extra chores. My leg isn’t too good, you see. A tank stand fell on it some years ago and crushed it.’

Audrey had never heard her mum say so many private words to a stranger. Mum seldom talked about the accident or whether her leg was painful.

‘Go on, dear. Take out that cup of tea before it goes cold.’ Mum sounded breathless.

Douglas had lost interest in the visitors already. He’d gone back to playing trains on the dry mud floor. Audrey stepped around him, the cup held carefully in both hands. She felt prickly with perspiration.

‘We don’t see many visitors,’ said Mum. ‘The children are shy.’

Audrey stepped outside.

‘This lost Aboriginal girl, she’s out there all alone. Anything could happen to her,’ said the policeman. ‘We’re taking her to a place where she’ll be looked after and she’ll learn to be useful. She needs discipline. It’s the best thing for her.’ He wiped tea from his mouth with one finger. ‘Perhaps the girl’s been around here and you haven’t realised. Have you had any food go missing, or clothes?’

Mum cleared her throat.

Audrey had her back to her mum, and she didn’t dare turn around. Her feet kept moving towards the man in the broad-brimmed hat by the car. If Mum told the policeman about the rabbit meat, he’d know Janet was nearby. He’d discover that Audrey had given food to Janet. Audrey didn’t know if they put little girls in gaol. They might. Janet had been in a place where they wouldn’t let her go home. Audrey figured they’d put

her

there too.

‘I think I’d notice if food went missing.’ Mum gave a tight laugh. It wasn’t her real laugh, but a stranger might think she was amused. ‘With five of us here and another on the way, we need every scrap we can find.’

Audrey approached the Aboriginal man and held out the cup.

She flicked a look at him, just for a second.

His right eye twitched.

Did it always do that, or had he just winked at her? Audrey didn’t dare look up at him again. He might see in her eyes that she was hiding something.

Janet had said a good tracker could find

anyone

,

anywhere

. He could tell everything but what they ate for lunch. And maybe even that. This tracker was already so close to where Janet was hiding. He’d find her, and then they’d take her away in the big black car. Her mum and aunties would be calling her and she might

never

answer.

Twenty-eight

The car drove off, back the way it came. For now, it was heading away from Janet.

If she saw the car, she’d be scared. She might try to hop away, but she wouldn’t get far. Or would she huddle inside the cubby and hope the policeman and tracker didn’t see her? Whatever happened, she was out there alone.

Audrey, Price and Mum stood outside the house, watching the dust cloud. Douglas was inside, still playing trains. He was the only one who didn’t feel the tightness in the air. It was just as though a thunderstorm was brewing, when the air was charged, ready to spark. But there were no clouds in the sky. The thunderstorm was right there on the ground.

Mum took Audrey’s hand.

Audrey squeezed her fingers.

‘You took that meat, didn’t you, sis?’ said Price.

Audrey nodded.

‘Where is she?’ Mum’s fingers twitched against Audrey’s.

It was a direct question. One that Audrey could not avoid answering. Besides, Mum already knew she’d seen ‘the girl’. Even if they hadn’t spoken the words to each other. And Audrey couldn’t lie straight out to Mum.

‘In my pirate cubby.’

Mum’s cheeks were still red, but there were white patches beneath her eyes.

‘What are we going to do?’ said Audrey. ‘They’ll send her to some place where she has to wash floors and carry big buckets. And it’s too hard for a little girl.’

‘I’m not sure we can do anything.’ Mum sighed. ‘It’s the law. That was a policeman. I don’t know what your father’s going to say about this. We should have told the police what we know. And we can’t actually

stop

them.’

‘You did good, Mum.’ Audrey squeezed her hand yet again. ‘Janet said her family are calling for her

every

day. She wants to go home to her mum. If a policeman came to take

me

away, Janet would try to stop them. She’s little, but she’s strong. Except for her bung foot. She can’t walk properly.’

Mum bit her lip.

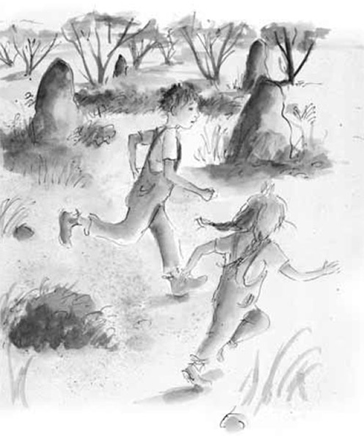

‘I have to warn her,’ said Audrey. ‘

Please

don’t tell me not to go.’ Her legs jiggled. Her feet wanted to run.

Her mum said nothing.

Audrey slipped her hand free of her mother’s warm grasp and swallowed hard.

‘If I go to gaol, you can have my treasure tin,’ she told Price. ‘There’s a ripper emu egg in there. You can put it on your string.’

Price rolled his eyes. ‘I don’t want your egg. You keep it. You won’t go to gaol. Besides, I’m coming with you.’