The Barn House (45 page)

Authors: Ed Zotti

THREE - WAY SWITCH IN ED'S PARENTS' HOUSE

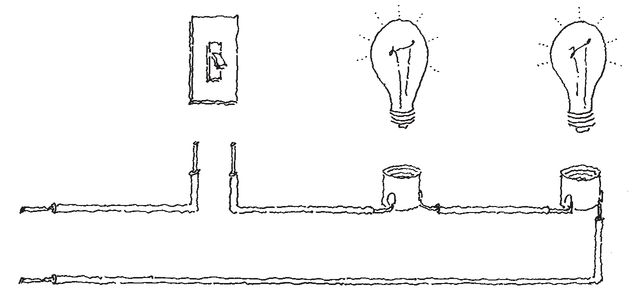

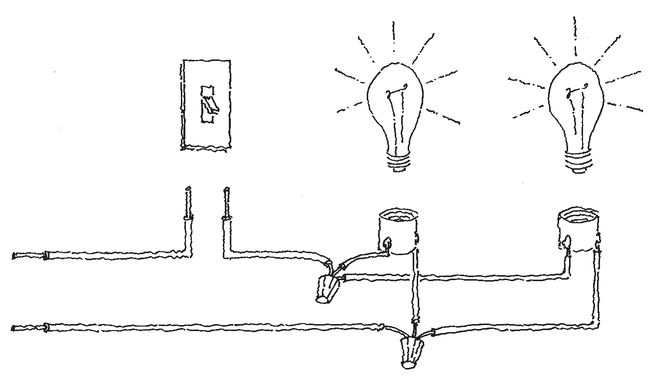

Appendix BWhen lights are connected in series, a single wire runs from power source to switch to bulb #1 to bulb #2 and back to the source. When lights are connected in parallel, each is connected independently to the source, with the wire running from source to switch to bulb and back to the source. It seemed pretty obvious to me that if the juice ran through one bulb you'd get full brightness, whereas if it ran through two you'd get half. It sure wasn't obvious to my old man, but then again he didn't have Charlie's illustrations as an explanatory aid.

LIGHTS WIRED IN SERIES (HALF - BRIGHTNESS)

LIGHTS WIRED IN PARALLEL (FULL BRIGHTNESS)

Appendix CCharlie has done his best with this one, but no question it's graduate-level wiring. It helps to know that (a) in house wiring, there's a “hot” wire and a “neutral” wire, notwithstanding that we're talking about alternating current here; (b) for safety, the neutral wire is groundedâthat is, it's electrically connected to the earth, typically by means of a wire attached to the house's cold water supply pipe, which is buried in the ground; (c) in a properly wired house, the metal housing of a fluorescent light fixture is also grounded, either by conduit (in Chicago) or a separate ground wire (most other places); (d) many old fluorescent light fixtures had a ballast that sometimes melted and shorted to the metal housing; (e) in a correctly wired lighting circuitâthat is, with the switch on the hot sideâa shorted ballast trips the circuit breaker and the lights won't turn on; but (f ) in a lighting circuit wired by a goof such as myself at age fourteenâthat is, with the switch on the neutral sideâa shorted ballast provides an alternative path to ground and the lights won't shut

off

. The heavy dotted line in the illustration indicates the current path.

off

. The heavy dotted line in the illustration indicates the current path.

The drawing below depicts one of the subtleties to which the Chief and I were introduced by Lee the electrician, which had to do with wiring a string of outlets. This will make little sense unless you know that: (a) outlets typically have two screws on either side, to which the wires are attached (many outlets also have push-in wiring terminals, in case you're in too much of a hurry to use the screws, but these don't change the argument); (b) in ancient days, it was customary when wiring a string of outlets to attach the wire from the upstream outlet to one screw and the wire from the downstream outlet to the other screw, to save a minute or two of installation time; (c) this was perfectly safe provided the two screws were connected by a fat metal strip, as was the case for many years; (d) however, at some pointâI'm chagrined to say it was probably around the time I was bornâmanufacturers quit using a fat metal strip in favor of a thin metal bridge, which could easily be broken off in case you wanted to separate the two sockets electrically; (e) from then on, daisy-chaining outlets together by connecting the wires to the screws was unwise, because the full current load was carried by the thin metal bridge, and if the load was unusually heavyâfor example, if you had a toaster at the far end, as shown in Charlie's illustrationâthe bridge might overheat or melt, overheating being the more serious problem due to the danger of fire. The correct procedure is shown on the left side of the illustrationâconnect the two wires directly with a short lead to the outlet. I ought to have learned this in year one of my electrical studies rather than year twenty-eight, but at least I learned it.

WIRING MULTIPLE OUTLETS

ED ZOTTI

is a longtime journalist and editor of the syndicated “Straight Dope” newspaper column by Cecil Adams. His articles and book reviews on subjects ranging from architecture to pigeon racing have appeared in such publications as the

Wall Street Journal

and the

New York Times

. He has published six books and is the recipient of a Citation for Excellence in Urban Design from the American Institute of Architects. Ed lives in Chicago with his wife, Mary Lubben, and his kids, Ryan, Ani, and Andrew.

is a longtime journalist and editor of the syndicated “Straight Dope” newspaper column by Cecil Adams. His articles and book reviews on subjects ranging from architecture to pigeon racing have appeared in such publications as the

Wall Street Journal

and the

New York Times

. He has published six books and is the recipient of a Citation for Excellence in Urban Design from the American Institute of Architects. Ed lives in Chicago with his wife, Mary Lubben, and his kids, Ryan, Ani, and Andrew.

1

Those having an interest in such things will find a diagram in Appendix A.

2

Those believing they're better equipped to handle this than my old man may inspect the diagram in Appendix B.

3

To a carpenter, a soffit is a boxlike piece of framing hung from the ceiling, commonly found above kitchen cabinets. (Another frequent use is to conceal air-conditioning ducts.) Soffit lights are built into the soffit to provide task lighting for the counters below.

4

Maybe not. See Appendix C.

5

An Italian beef is a sandwich made of spicy sliced beef on Italian bread drenched in juice. Having eaten this delicacy most of my life and assumed it was a staple of Italian national cuisine, I was surprised to learn in college that it was available only in Chicago. This was like finding out Chicago was the only place that had girls. Why Italian beef hasn't found a wider audience is an abiding mystery. The cheese steak, as I suppose most inhabitants of the East Coast know, is a sandwich consisting of chopped grilled steak with melted cheese on Italian bread, which originated at a place I know only as Pat's in Philadelphia. Like Italian beef it's exceedingly tasty, but, also like Italian beef, will kill you if consumed in excess, meaning oftener than maybe once a year. However, I venture to say anyone departing this vale of tears as a result of Italian beef or cheese steak overdose will die with a smile.

6

I include this recognizing that even among confirmed city dwellers mass transit is more tolerated than enjoyed, but it remains one of the quintessential urban experiences, and riding it is not without, shall we say, opportunities for personal growth. One night during freshman year at college I and my room-mate Mike (a different Mike) were riding the L, as the rapid transit system in Chicago is known, when a large middle-aged man across the aisle began addressing us in a loud but incomprehensible voice, owing to the fact that he was stone drunk. Growing agitated at his evident failure to communicate, the man restated his proposition several times in a progressively more belligerent tone. Still no go. Mike, a nice Jewish boy from suburban Philadelphia, looked completely terrified, and I felt a little anxious myself. On the third or fourth iteration, however, it dawned on me what the man was saying. “Right!” I shouted back. “Joe Louis! Joe Louis was the world's greatest fighter!” Delighted at having made himself understood, the man broke into a grin, shook our hands, and staggered off at the next stop.

6

I include this recognizing that even among confirmed city dwellers mass transit is more tolerated than enjoyed, but it remains one of the quintessential urban experiences, and riding it is not without, shall we say, opportunities for personal growth. One night during freshman year at college I and my room-mate Mike (a different Mike) were riding the L, as the rapid transit system in Chicago is known, when a large middle-aged man across the aisle began addressing us in a loud but incomprehensible voice, owing to the fact that he was stone drunk. Growing agitated at his evident failure to communicate, the man restated his proposition several times in a progressively more belligerent tone. Still no go. Mike, a nice Jewish boy from suburban Philadelphia, looked completely terrified, and I felt a little anxious myself. On the third or fourth iteration, however, it dawned on me what the man was saying. “Right!” I shouted back. “Joe Louis! Joe Louis was the world's greatest fighter!” Delighted at having made himself understood, the man broke into a grin, shook our hands, and staggered off at the next stop.

6

I hasten to say this wasn't literally the case. So far as I knew, the kids in what was known in the neighborhood as the “bad building” behind us weren't affiliated with the Latin Kings street gang; they were freelance delinquents. Even that may be putting it too strongly. While staving in my neighbor's garage door with a truck couldn't be dismissed as youthful hijinks, experience suggested that many of the balls, toy cars, and like items that went missing were carried off by five-year-olds unclear on the concept of private property. I still wonder what happened to those four plastic lawn chairs, though.

7

One recognizes that with the funguslike spread of Starbucks to the suburbs this isn't as true as it used to be.

8

Some city people, it must be said, are in denial about this. No disrespect, but New Yorkers are by far the worst offenders. I talked once with a fellow who had moved from Chicago to Brooklyn for career purposes, and who was having a hard time making the adjustment. “People come up with the weirdest rationalizations for living here,” he said. “I wanted to buy a frying pan, and a guy told me, âWell, one thing about New York, you can always find a frying pan.' And I thought,

I should hope to God.

”

I should hope to God.

”

9

Although there is still a large retail establishment located in the building formerly occupied by Marshall Field's, the store itself, alas, is no more, having been sold to another company. I forget the name of it.

10

Crime and neglect by no means exhaust the list of urban perils. In 1992, the year before we bought the Barn House, gas utility workers in a gentrifying Chicago neighborhood called River West opened a valve on a pressure regulator they were overhauling, inadvertently sending a surge of high-pressure gas through the mains serving the surrounding neighborhood. Within a short time eighteen buildings had blown up, killing four people. Although it soon dawned on the gas workers that the howling sirens, explosions, fires, and chaos surrounding them were quite likely their fault, they didn't shut off the gas for forty minutes pending instructions from their superiors. A few months later, only a few blocks away, a disused freight tunnel passing beneath the Chicago River collapsed, allowing hundreds of millions of gallons of water to flood into the city's extensive freight-tunnel network, which had formerly been used for deliveries, ash removal, and so on, and connected with the basements of most larger pre-World War II buildings in downtown Chicago. The flood knocked out several electrical substations, caused losses of nearly $2 billion, and rendered a portion of the city's subway system unusable for three and a half weeks. An investigation determined that the tunnel roof had been damaged almost two years previously by a contractor driving pilings into the riverbed near a bridge. Although an inspector had detected the damage almost immediately and recognized the danger, the city bureaucracy didn't consider the matter urgent and the tunnel had gone unrepaired. My point isn't that the people in charge of the municipal infrastructure in Chicago are unusually incompetentâhey, we all make mistakesâbut that when things go wrong in an urban context, it's not just those immediately involved who feel the heat.

Other books

Earth Colors by Sarah Andrews

Pierced: Pierced Trilogy Boxed Set by Lashell Collins

The Twelve Dates of Christmas by Lisa Dickenson

Private Relations by Nancy Warren

Along Came a Cowboy by Christine Lynxwiler

Thorn Abbey by Ohlin, Nancy

Accidentally Married by Victorine E. Lieske

Black Lace Quickies 3 by Kerri Sharpe

A Brutal Tenderness by Marata Eros

A Good Night for Ghosts by Mary Pope Osborne