The Battle for Gotham (31 page)

Read The Battle for Gotham Online

Authors: Roberta Brandes Gratz

Tags: #History, #United States, #20th Century

The Secret Life of New York Industry

Urban manufacturing is mostly unrecognized by economic development experts, or seen as an anachronism. This is a mistake.

SASKIA SASSEN,

economist

A city is a settlement that consistently generates its economic growth from its own local economy.

JANE JACOBS,

The Economy of Cities

D

onald and I were married in May 1965, five months after I became a full reporter. We returned from our honeymoon, and without telling him, I changed my byline from Roberta Brandes to Roberta Gratz. It did not seriously occur to me to keep my maiden name, something so many professional women do today, including our two daughters, Laura and Rebecca. But three months later my father died. I learned from my mother that my father had been saddened—though he did not tell me—that I had dropped the family name. In his memory—not for feminist reasons—I retrieved the maiden name and changed the byline to Roberta Brandes Gratz. To some of the editors this was a nuisance at best, an annoyance at worst.

1

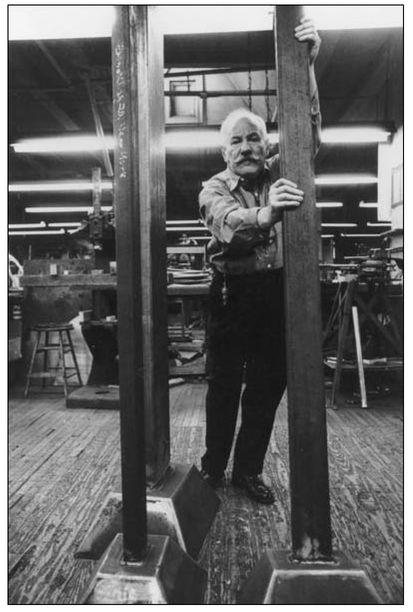

6.1 Ramsammy Pullay, nicknamed Dez, has been with the company since 1996. Here he is “benching” or bending a steel furniture component.

Joshua Velez

.

Donald, like me, had been living in the city with no interest in leaving. He had moved in happily after college, having grown up in Pelham, a near-in Westchester suburb. He took a one-room ground-floor apartment facing a small courtyard on East Twenty-sixth Street. He walked to work.

In 1955 Donald had joined the family metal fabrication business, started in 1929 by his father and a partner.

2

Metal fabrication simply means a process by which objects are made out of metal. Steel, aluminum, and copper, primarily, are bent, drilled, welded, polished, and assembled into chairs, tables, architectural elements, exercise equipment, and custom-designed objects. None of this is mass produced. Instead, skilled and semiskilled workmen individually operate the assorted machines that make up the process. Treitel-Gratz (now Gratz Industries) was located on the sixth floor of a six-story loft building on East Thirty-second Street between Lexington and Third Avenues.

Watching the fate of this building and business unfold was for me another source of learning about both the changing city and the working of the urban economy. The evolution of the Gratz family business continues to be instructive, just as my own father’s dry-cleaning business provided urban lessons. Gratz Industries, like most city manufacturers, faces an ever-changing array of challenges from both the national economy and city policies. More than eighty years old, it is as contemporary as it ever was.

3

A 1997 report,

Designed in New York/Made in New York

, noted about the city’s “large, complex manufacturing sector”: “Although manufacturing in New York struggles with high costs and a continual need to reinvent itself, the frequent public pronouncements of its demise are, as the pundit said, premature. Twelve thousand firms employing a quarter of a million production workers endow New York with what is still one of the densest concentrations of manufacturing in the United States.”

4

MANUFACTURING: EVER CHANGING

Treitel-Gratz had moved to Thirty-second Street in the 1930s from a small brownstone on lower Lexington where it started in the 1920s. The East Thirties were filled with furniture manufacturers. By the 1960s, an assortment of small manufacturers and esoteric businesses occupied this loft building: a menu printer, a bra manufacturer, a cabinetmaker, three decorative wood finishers, a manufacturer of machines for glove makers, a type-setter, an umbrella manufacturer, a drapery and slipcover maker, a dinette furniture seller, a gold stamper, a store display maker, and a woman who raised rats. Quite a combination! Some of the businesses worked together on special jobs and were spontaneously and conveniently clustered for the decorating trade. We did metalwork for the cabinetmaker and store display maker and used the upholsterer when we needed that work. Everyone did odd jobs for one another. It is difficult to place a monetary or operational value on this kind of synergy. “By the early 1930s, the company had established itself as the metal shop of choice for, among others, the celebrated industrial designer Donald Deskey,” wrote Charles Gandee in an article about the company titled “Heavy Metal” in the

New York Times Home Design Magazine

in spring 2003. Deskey was then doing the celebrated interior furniture for Radio City Music Hall, including the Art Moderne furniture for the office of the great impresario S. L. Rothafel, known as Roxy. Other great industrial designers, like Raymond Loewy with his iconic Coca-Cola machine, George Nelson with his furniture prototypes, and John Ebstein with his toy models for Gabriel Industries, were also customers. The company’s history parallels the history of twentieth-century design.

In 1948, Hans Knoll, a German émigré, wanted to bring the furniture of legendary Bauhaus architect Mies van der Rohe to the United States and enlisted the company to engineer and manufacture the Mies line of chairs and tables now considered classics—Barcelona, Bruno, Tugendhat—all first exhibited at the 1929 International Industrial Exposition in Barcelona. In 1958 architect Philip Johnson turned to Deskey for the interior of the Four Seasons Restaurant when it opened in the base of the Mies-designed Seagram Building on Park Avenue that was also filled with Mies furniture. Johnson was a protégé of Mies and coarchitect on the building, and he designed the restaurant interior with Garth Huxtable. That restaurant, a city-designated interior landmark, was—and still is—furnished with the classic Mies furniture.

In the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, American furniture design was in its heyday. Treitel-Gratz furniture and metalwork were going into scores of new office buildings in New York, Chicago, and other cities and suburbs, especially those designed by Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill.

But aside from the building interiors, Knoll furniture, a line of furniture designed by Nicos Zographos, and the industrial-design model work, most of Treitel-Gratz business in the 1950s and early 1960s was actually precision sheet metal for electronic equipment, before that field of work moved to California with the aircraft industry. But as can—and often must—happen in any kind of business, especially manufacturing, as one product line diminishes or moves away, another fills the spot. It happened for Treitel-Gratz as the art world was transformed in the 1960s. Isamu Noguchi had long been a customer for many of his metal sculptures since the 1940s, but Alexander Liberman was the first of a new group of sculptors who came to Treitel-Gratz not just for its reputation for skillful implementation and metal craftsmanship but because of its proximity to Manhattan. Liberman often visited the shop and worked alongside one of our machinists.

People fail to understand the importance of New York City-based manufacturing if they don’t recognize the value that industry has to the fields, like art and architecture, for which the city is famous. For designers, being able to implement ideas locally is critical to their craft. Surely, it was true for the long line of leading artists, architects, and furniture designers who passed through our factory. We’ve always been convenient to a subway. “Urban manufacturing needs to be done where it is used,” observes Columbia University professor Saskia Sassen, who has written several books on global capital and the mobility of labor. “This is not an old, outdated condition but a very contemporary one. This is not about the past; this is cutting edge. The specialized service economy demands it; the new economy needs this kind of manufacturing.” Designers benefit from proximity in many ways but none so important as what architect David Childs calls “the knowledge of the skilled workers who operate the machines, work with the materials and understand what those can do. They know things you can’t put in books. Designers need that knowledge more than ever.”

THE CHANGING ART WORLD CHANGED US

In the 1960s Alexander Liberman brought sculptor Barnett Newman to the shop. Newman subsequently brought in a whole group of young Minimalists who were either his friends or protégés, all little known. The Minimalists were changing the nature of contemporary art. Many of them made a big splash with the 1966 Minimalist show Primary Structures at the Jewish Museum. That landmark exhibit defined the Minimalist movement. Donald Judd, Walter De Maria, Sol Lewitt, Robert Rauschenberg, Forrest Myers, Michael Heizer, Robert Indiana, and more—it was a cast of soon-to-be stars.

Just as the company history parallels the evolution of interior and industrial design of the twentieth century, so does it parallel the evolution of the Minimalist and post-Abstract Expressionist art that emerged in the 1960s when the center of the art world shifted from Paris to New York. In New York, the art scene shifted from the Upper East Side to SoHo with the new trend in larger and larger artworks and the opening of the Paula Cooper Gallery in 1967. Key artists exhibiting there came to us.

From the 1960s on, office furniture, custom metalwork, and sculpture dominated. As the field of architecture evolved, so did the content of our production. I. M. Pei, Charles Gwathmey, Deborah Burke, Masimo and Lila Vignelli, Robert A. M. Stern, James Polshek, and Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill, and others, looked to the company to solve fabrication challenges.

Change is inevitable in manufacturing. One big change with a company like ours can shift the whole picture. In the mid-1960s, Knoll took its business away to its own manufacturing operation in Pennsylvania. At the same time, a new item for production was added. Romana Kryzanowska, the chosen successor to innovative exercise master Joseph Pilates, came to Donald to produce metal exercise equipment, long before his Pilates Method became the rage. In time, Pilates exercise equipment surpassed custom metalwork and furniture as the company’s primary product.

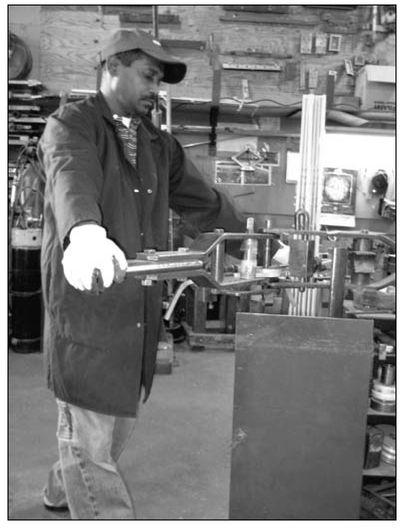

6.2 Barnett Newman with his first steel sculpture,

Here II

(1965), at Gratz Industries.

Ugo Mulas, courtesy of the Barnett Newman Foundation.