The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (28 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

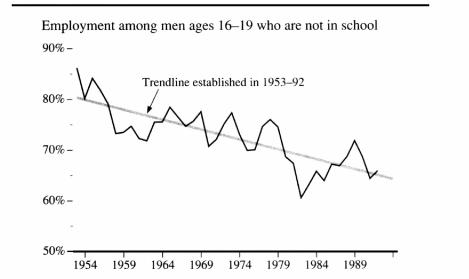

Since mid-century, teenage boys not in school are increasingly not employed either

Sources:

Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1982, Table C-42; unpublished data provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Although the economy has gone up and down over the last forty years and the employment of these young men with it, the long-term employment trend of their employment has been downhill. The overall drop has not been small. In 1953, the first year for which data are available, more than 86 percent of these young men had jobs. In 1992, it was just 66 percent.

Large macroeconomic and macrosocial forces, which we will not try to cover, have been associated with this trend in employment.

1

In this chapter, we are concerned with what intelligence now has to do with getting and holding a job. To explore the answer, we divide the employment problem into its two constituent parts, the unemployed and those not even looking for work. All of the analyses that follow refer exclusively to whites; in this case white males.

To qualify as “participating in the labor force,” it is not necessary to be employed; it is necessary only to be looking for work. Seen from this perspective, there are only a few valid reasons why a man might not be in the labor force. He might be a full-time student; disabled; institutionalized or in the armed forces; retired; independently wealthy; staying at home caring for the children while his wife makes a salary. Or, it may be argued, a man may legitimately be out of the labor force if he is convinced that he cannot find a job even if he tries. But this comes close to exhausting the list of legitimate reasons.

As of the 1990 interview wave, the members of the NLSY sample were in an ideal position for assessing labor force participation. They were 25 to 33 years old, in their prime working years, and they were indeed a hardworking group. Ninety-three percent of them had jobs. Fewer than 5 percent were out of the labor force altogether. What had caused that small minority to drop out of the labor force? And was there any relationship between being out of the labor force and intelligence?

One such relationship was entirely predictable. A few men were out of the labor force because they were still in school in their late 20s and early 30s—most of them in law school, medical school, or studying for the doctorate. They were concentrated in the top cognitive classes. But this does not tell us much about who leaves the labor force. We will exclude them from the subsequent analysis and focus on men who were out of the labor force for reasons other than school.

To structure the analysis, let us ask who spent at least a month out of the labor force during calendar year 1989. Here is the breakdown of labor force dropout by cognitive class for white males.

2

Dropout from the labor force rose as cognitive ability fell. The percentage of Class V men who were out of the labor force was a little more than twice the percentage for men in Class I.

| Which White Young Men Spent a Month or More Out of the Labor Force in 1989? | |

|---|---|

| Cognitive Class | Percentage |

| I Very | 10 |

| II Bright | 14 |

| III Normal | 15 |

| IV Dull | 19 |

| V Very dull | 22 |

| Overall average | 15 |

S

OCIOECONOMIC

B

ACKGROUND

V

ERSUS

C

OGNITIVE

A

BILITY.

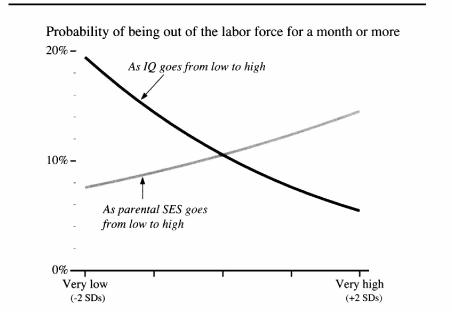

The next step, in line with our standard procedure, is to examine how much of the difference may be accounted for by the man’s socioeconomic background. The thing to be explained (the dependent variable) is the probability of spending at least a month out of the labor force in 1989. Our basic analysis has the usual three explanatory variables: parental SES, age, and IQ. The results are shown in the figure below. In this analysis, we exclude all men who in either 1989 or 1990 reported that they were in school, the military, or were physically unable to work.

These results are the first example of a phenomenon you will see again in the chapters of Part II. If we had run this analysis with just socioeconomic background and age as the explanatory variables, we would have found a mildly interesting but unsurprising result: Holding age constant, white men from more privileged backgrounds have a modestly smaller chance of dropping out of the labor force than white men from deprived

backgrounds. But when IQ is added to the equation, the role of socioeconomic background either disappears entirely or moves in the opposite direction. Given equal age and IQ, a young man from a family with high socioeconomic status was

more

likely to spend time out of the labor force than the young man from a family with low socioeconomic status.

3

In contrast, IQ had a large positive impact on staying at work. A man of average age and socioeconomic background in the 2d centile of IQ had almost a 20 percent chance of spending at least a month out of the labor force, compared to only a 5 percent chance for a man at the 98th centile.

IQ and socioeconomic background have opposite effects on leaving the labor force among white men

Note: For computing the plot, age and either SES (for the black curve) or IQ (for the gray curve) were set at their mean values.

It is not hard to imagine why high intelligence helps keep a man at work. As Chapter 3 discussed, competence in the workplace is related to intelligence, and competent people more than incompetent people are likely to find the workplace a congenial and rewarding place. Hence,

other things equal, they are more likely than incompetent people to be in the labor force. Intelligence is also related to time horizons. A male in his 20s has many diverting ways to spend his time, from traveling the world to seeing how many women he can romance, all of them a lot more fun than working forty hours a week at a job. A shortsighted man may be tempted to take a few months off here and there; he thinks he can always pick up again when he feels like it. A farsighted man tells himself that if he wants to lay the groundwork for a secure future, he had better establish a record as a reliable employee now, while he is young. Statistically, smart men tend to be more farsighted than dumb men.

In contrast to IQ, the role of parental SES is inherently ambiguous. One possibility is that growing up in a privileged home foretells low dropout rates, because the parents in such households socialize their sons to conventional work. But this relationship may break down among the wealthy, whose son has the option of living comfortably without a weekly paycheck. In any case, aren’t working-class homes also adamant about raising sons to go out and get a job? And don’t young men from lower-class homes have a strong economic incentive to stay in the labor force because they are likely to need the money? The statistical relationship with parental SES that shows up in the analysis suggests that higher status may facilitate labor force dropout, at least for short periods.

The analysis of labor force dropout is also the first example in Part II of a significant relationship that is nonetheless modest. When we know from the outset that 78 percent of white men in Class V—borderline retarded or below—did

not

drop out of the labor force for as much as a month, we can also infer that all sorts of things besides IQ are important in determining whether someone stays at work. The analysis we have presented adds to our understanding without enabling us to explain fully the phenomenon of labor force dropout.

E

DUCATION.

Conducting the analysis separately for our two educational samples (those with a bachelor’s degree, no more and no less, and those with a high school diploma, no more and no less) does not change the picture. High intelligence played a

larger

independent role in reducing labor force dropout among the college sample than among the high school sample. And for both samples, high socioeconomic background did not decrease labor force dropout independent of IQ and age. Once

again, the probability of dropout actually increased with socioeconomic background.

In the preceding analysis, we excluded all the cases in which men reported that they were unable to work. But it is not that simple. Low cognitive ability increases the risk of being out of the labor force for healthy young men, but it also increases the risk of not being healthy. The breakdown by cognitive classes is shown in the following table. The relationship of IQ with both variables is conspicuous but more dramatic for men reporting that their disability prevents them from working. The rate per 1,000 of men who said they were prevented from working by a physical disability jumped sevenfold from Class III to Class IV, and then more than doubled again from Class IV to Class V.

| Job Disability Among Young White Males | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. per 1,000 Who Reported Being Prevented from Working by Health Problems | Cognitive Class | No. per 1,000 Who Reported Limits in Amount or Kind of Work by Health Problems |

| 0 | I Very Bright | 13 |

| 5 | II Bright | 21 |

| 5 | III Normal | 37 |

| 36 | IV Dull | 45 |

| 78 | V Very dull | 62 |

| 11 | Overall average | 33 |

A moment’s thought suggests a plausible explanation: Men with low intelligence work primarily in blue-collar, manual jobs and thus are more likely to get hurt than are men sitting around conference tables. Being injured is more likely to shrink the job market for a blue-collar worker than a for a white-collar worker. An executive with a limp can still be an executive; a manual laborer with a limp faces a more serious job impediment. This plausible hypothesis appears to be modestly confirmed in a simple cross-classification of disabilities with type of job.

More blue-collar workers reported some health limitation than did white-collar workers (38 per 1,000 versus 28 per 1,000), and more blue-collar workers reported being prevented from working than did white-collar workers (5 per 1,000 versus 2 per 1,000).

But the explanation fails to account for the relationship of disability with intelligence. For example, given average cognitive ability and age, the odds of having reported a job limitation because of health were about 3.3 percent for white men working in white-collar jobs compared to 3.8 percent for white men working in blue-collar jobs, a very minor difference. But

given that both men have blue-collar jobs,

the man with an IQ of 85 had double the probability of a work disability of a man with an IQ of 115.

Might there be something within job categories to explain away this apparent relationship of IQ to job disability? We explored the question from many angles, as described in the extended note, and the finding seems to be robust. For whatever reasons, white men with low IQs are more likely to report being unable to work because of health than their smarter counterparts, even when the occupational hazards have been similar.

4

Why might intelligence be related to disability, independent of the line of work itself? An answer leaps to mind: The smarter you are, the less likely that you will have accidents. In Lewis Terman’s sample of people with IQs above 140 (see Chapter 2), accidents were well below the level observed in the general population.

5

In other studies, the risk of motor vehicle accidents rises as the driver’s IQ falls.

6

Level of education—to some degree, a proxy measure of intelligence—has been linked to accidents and injury, including fatal injury, in other activities as well.

7

Smarter workers are typically more productive workers (see Part I), and we can presume that some portion of what makes a worker productive is that he avoids needless accidents.