The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (37 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

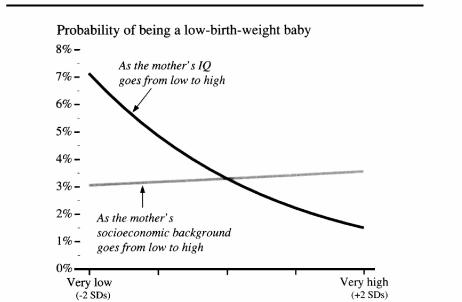

A white mother’s IQ has a significant role in determining whether her baby is underweight while her socioeconomic background does not

Note: For computing the plot, age and either SES (for the black curve) or IQ (for the gray curve) were set at their mean values.

A low IQ is a major risk factor, whereas the mother’s socioeconomic background is irrelevant. A mother at the 2d centile of IQ had a 7 percent chance of giving birth to a low-birth-weight baby, while a mother at the 98th percentile had less than a 2 percent chance.

Adding Poverty.

Poverty is an obvious potential factor when trying to explain low birth weight. Overall, poor white mothers (poor in the year before birth) had 61 low-birth-weight babies per 1,000, while other white mothers had 36. But poverty’s independent role was small and statistically insignificant, once the other standard variables were taken into account. Meanwhile, the independent role of IQ remained as large, and that of socioeconomic background as small, even after the effects of poverty were extracted.

Can Mothers Be Too Smart for Their Own Good?

The case of low birth weight is the first example of others you will see in which the children of white women in Class I have anomalously bad scores. The obvious, but perhaps too obvious, culprit is sample size. The percentage of low-birth-weight babies for Class I mothers, calculated using sample weights, was produced by just two low-birth-weight babies out of seventy-four births.

54

The sample sizes for white Class I mothers in the other analyses that produce anomalous results are also small, sometimes under fifty and always under one hundred, while the sample sizes for the middle cognitive classes number several hundred or sometimes thousands.On the other hand, perhaps the children of mothers at the very top of the cognitive distribution do in fact have different tendencies than the rest of the range. The possibility is sufficiently intriguing that we report the anomalous data despite the small sample sizes, and hope that others will explore where we cannot. In the logistic regression analyses, where each case is treated as an individual unit (not grouped into cognitive classes), these problems of sample size do not arise.

Adding mothers age at the time of birth.

It is often thought that very young mothers are vulnerable to having low-birth-weight babies, no matter how good the prenatal care may be.

55

This was not true in the NLSY data for white women, however, where the mothers of low-birth weight babies and other mothers had the same mean (24-2 years).

In sum, neither the mother’s age in the NLSY cohort, nor age at birth of the child, nor poverty status, nor socioeconomic background had any appreciable relationship to her chances of giving birth to a low-birth-weight baby after her cognitive ability had been taken into account.

Adding education.

Among high school graduates (no more, no less) in the NLSY, a plot of the results of the standard analysis looks visually identical to the one presented for the entire sample, but the sample of low-birth-weight babies was so small that the results do not reach statistical significance. Among the college graduates, low-birth-weight babies were so rare (only six out of 277 births to the white college sample) that a multivariate analysis produced no interpretable results. We do not know whether it is the education itself, or the self-selection that goes into having more education, that is responsible for their low incidence of underweight babies.

Though we have not been able to find any studies of cognitive ability and infant mortality, it is not hard to think of a rationale linking them. Many things can go wrong with a baby, and parents have to exercise both watchfulness and judgment. It takes more than love to childproof a house effectively; it also takes knowledge and foresight. It takes intelligence to decide that an apparently ordinary bout of diarrhea has gone on long enough to make dehydration a danger; and so on. Nor is simple knowledge enough. As pediatricians can attest, it may not be enough to tell new parents that infants often spike a high fever, that such episodes do not necessarily require a trip to the hospital, but that they require careful attention lest such a routine fever become life threatening. Good parental judgment remains vital. For that matter, the problem facing pediatricians dealing with children of less competent parents is even more basic than getting them to apply good judgment: It is to get such mothers to administer the medication that the doctor has provided.

This rationale is consistent with the link that has been found between education and infant mortality. In a study of all births registered in California in 1978, for example, infant deaths per 1,000 to white women numbered 12.2 for women with less than twelve years of education,

8.3 for those with twelve years, and 6.3 for women with thirteen or more years of education, and the role of education remained significant after controlling for birth order, age of the mother, and marital status.

56

We have been unable to identify any study that uses tested IQ as an explanatory factor, and, with such a rare event as infant mortality, even the NLSY cannot answer our questions satisfactorily. The results certainly suggest that the questions are worth taking seriously. As of the 1990 survey, the NLSY recorded forty-two deaths among children born to white women with known IQ. Some of these deaths were presumably caused by severe medical problems at birth and occurred in a hospital where the mother’s behavior was irrelevant.

57

For infants who died between the second and twelfth month (the closest we can come to defining “after the baby had left the hospital”), the mothers of the surviving children tested six points higher in IQ than the mothers of the deceased babies. (The difference for mothers of children who died in the first month was not quite three points and for the mothers of children who were older than 1 year old when they died, virtually zero.) The samples here are too small to analyze in conjunction with socioeconomic status and other variables.

In Chapter 5, we described how the high-visibility policy issue of children in poverty can be better understood when the mother’s IQ is brought into the picture. Here, we focus more specifically on the poverty in the early years of a child’s life, when it appears to be an especially important factor (independent of other variables) in affecting the child’s development.

58

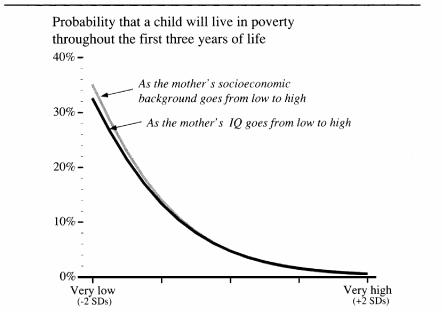

The variable is much more stringent than simply experiencing poverty at some point in childhood. Rather, we ask about the mothers of children who lived under the poverty line throughout their first three years of life, comparing them with mothers who were not in poverty at any time during the child’s first three years. The standard analysis is shown in the figure below. There are few other analyses in Part II that show such a steep effect for both intelligence and SES. If the mother has even an average intelligence and average socioeconomic background, the odds of a white child’s living in poverty for his or her first three years were under 5 percent. If either of those conditions fell below average, the odds increased steeply.

A white mother’s IQ and socioeconomic background each has a large independent effect on her child’s chances of spending the first three years of life in poverty

Note: For computing the plot, age and either SES (for the black curve) or IQ (for the gray curve) were set at their mean values.

When we ask whether the mother was in poverty in the year prior to birth, it turns out that a substantial amount of the effect we attribute to socioeconomic background in the figure really reflects whether the mother was already in poverty when the child was born. If you want to know whether a child will spend his first three years in poverty, the single most useful piece of information is whether the mother was already living under the poverty line when he was born. Nevertheless, adding poverty to the equation does not diminish a large independent role for cognitive ability. A child born to a white mother who was living under the poverty line but was of average intelligence had almost a 49 percent chance of living his first three years in poverty. This is an extraordinarily high chance of living in poverty for American whites as a whole. But if the same woman were at the 2d centile of intelligence, the odds rose to 89 percent; if she were at the 98th centile, they dropped to 10 percent.

59

The changes in the odds were proportionately large for women who were not living in poverty when the child was born.

For children of women with a high school diploma (no more, no less), the relationships of IQ and socioeconomic background to the odds that a child would live in poverty are the same as shown in the figure above—almost equally important, with socioeconomic background fractionally more so—except that the odds are a little lower than for the whole sample (the highest percentages, for mothers two standard deviations below the mean, are in the high 20s, instead of the mid-30s). As this implies, the highest incidence of childhood poverty occurs among women who dropped out of school Among the white college sample (a bachelor’s degree, no more and no less), there was nothing to analyze; only one child of such mothers had lived his first three years in poverty.

In 1986, 1988, and 1990, the NLSY conducted special supplementary surveys of the children and mothers in the sample. The children were given tests of mental, emotional, and physical development, to which we shall turn presently. The mothers were questioned about their children’s development and their rearing practices. The home situation was directly observed. The survey instruments were based on the so-called HOME (Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment) index.

60

Dozens of questions and observations go into creating the summary measures, many of them interesting in themselves. Children of the brightest mothers who also tend to be the best educated and the most affluent) have a big advantage in many ways, especially on such behaviors as reading to the child. On other indicators that are less critical in themselves, but indirectly suggest how the child is being raised, children with smarter mothers also do better. For example, mothers in the top cognitive classes use physical punishment less often (though they agree in principle that physical punishment can be an appropriate response), and the television set is off more of the time in the homes of the top cognitive classes.

Treating the HOME index as a continuous scale running from “very

bad” to “very good” home environments, the advantages of white children with smarter mothers were clean The average child of a Class V woman lived in a home at the 32d percentile of home environment, while the home of the average child of a Class I woman was at the 76th percentile. The gradations for the three intervening classes were regular as well.

61

Overall, the correlation of the HOME index with IQ for white mothers was +.24, statistically significant but hardly overpowering.

In trying to identify children at risk, this way of looking at the relationship is not necessarily the most revealing. We are willing to assume that a child growing up in a home at the 90th centile on the HOME index has a “better” environment than one growing up at the 50th. Perhaps the difference between a terrific home environment and a merely average one helps produce children who are at the high end on various personality and achievement measures. But it does not necessarily follow that the child in the home at the 50th centile is that much more at risk for the worst outcomes of malparenting than the child at the 90th centile. Both common sense and much of the scholarly work on child development suggest that children are resilient in the face of moderate disadvantages and obstacles and, on the other hand, that parents are frustratingly unable to fine-tune good results for their children.