The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (71 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

Source:

Iowa Testing Program, University of Iowa.

Taken as a whole, the data from representative samples of high school students describe an American educational system that was probably improving from the beginning of the century into the mid-1960s, underwent a decline into the mid-1970s—steep or shallow, depending on the study—and rebounded thereafter. Conservatively, average high school students seem to be as well prepared in math and verbal skills as

they were in the 1950s. They may be better prepared than they have ever been. If U.S. academic skills are deficient in comparison with other nations, they have been comparatively so for a long time and are probably better than they were.

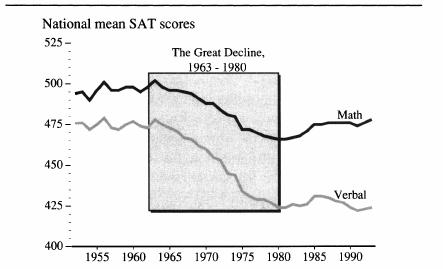

Having questioned the widespread belief that high school education today is worse on average than it used to be, we now reverse course and offer some reasons for thinking that it has gotten worse for one specific group of students: the pool of youths in the top 10 to 20 percent of the cognitive ability distribution who are prime college material. To make this case, we will focus on the best-known educational trend, the decline in SAT scores. Visually, the story is told by what must be the most frequently published trendlines in American educational circles, as shown below.

25

The steep drop from 1963 to 1980 is no minor statistical fluctuation. Taken at face value, it tells of an extraordinarily large downward shift in academic aptitude—almost half a standard deviation on the Verbal, almost a third of a standard deviation on the Math.

26

And yet we have just finished demonstrating that this large change is not reflected in the aggregate national data for high school students. Which students, then, account for the SAT decline? We try to answer that question in the next few paragraphs, as we work our way through the most common explanation of the decline. To anticipate our conclusion, the standard explanation does not stand up to the data. We are left with compelling evidence of a genuine decline in the intellectual resources of our brightest youngsters.

Forty-one years of SAT scores

Source:

The College Board. Scores for 1952-1969 are based on all tests administered during the year; 1970-1993 on the most recent test taken by seniors.

The most familiar explanation of the great decline is that the SAT was “democratized” during the 1960s and 1970s. The pool of people taking the test expanded dramatically, it is said, bringing in students from disadvantaged backgrounds who never used to consider going to college. This was a good thing, people agree, but it also meant that test scores went down—a natural consequence of breaking down the old elites. The real problem is not falling SAT scores but the inferior education for the disadvantaged that leads them to have lower test scores, according to the standard account.

27

This common view is mistaken. To make this case requires delving into the details of the SAT and its population.

28

To summarize a complex story: During the 1950s and into the early 1960s, the SAT pool expanded dramatically, but scores remained steady. In the mid-1960s, scores started to decline, but, by then, many state universities had become less selective in their admissions process, often dropping the requirement that students take SATs, and, as a result, many of the students in the middle level of the pool who formerly took the SAT stopped doing so. Focusing on the whites taking the SAT (thereby putting aside the effects of the changing ethnic composition of the pool), we find that

throughout most of the white SAT score decline, the white SAT pool was shrinking, not expanding.

We surmise that the white population of test takers during this period was probably getting more exclusive socioeconomically, not less. It is virtually impossible that it was becoming more democratized in any socioeconomic sense.

After 1976, when detailed background data on white test takers become available, the evidence is quite explicit. Although the size of the pool once again began to expand during the 1980s, neither parental income nor parental education of the white test takers changed.

29

After factoring in the effects of changes in the gender of the pool and changes in the difficulty of the SAT, we conclude that the aggregate real decline

from 1963 to 1976 among whites taking the SAT was on the order of thirty-four to forty-four points on the Verbal and fifteen to twenty-five points on the Math. From 1976 to 1993, the real white losses were no more than a few additional points on the Verbal. On the Math, white scores improved about three or four points in real terms after changes in the pool are taken into account. Or in other words, when everything is considered, there is reason to conclude that the size of the drop in the SAT as shown in that familiar, unsophisticated graphic with which we opened the discussion is for practical purposes the same size and shape as the real change in the academic preparation of white college-bound SAT test takers. Neither race, class, parental education, composition of the pool, nor gender can explain this decline of forty-odd points on the Verbal score and twenty-odd points on the Math for the white SAT-taking population during the 1960s and 1970s. For whatever reasons, during the 1960s America stopped doing as well intellectually by the core of students who go to college.

Rather than democratization, the decline was more probably due to leveling down, or mediocritization: a downward trend of the educational skills of America’s academically most promising youngsters toward those of the average student. The net drop in verbal skills was especially large, much larger than net drop in math skills. It affected even those students with the highest levels of cognitive ability.

Does this drop represent a fall in realized intelligence as well as a drop in the quality of academic training? We assume that it does to some extent but are unwilling to try to estimate how much of which. The SAT score decline does underscore a frustrating, perverse reality: However hard it may be to raise IQ among the less talented with discrete interventions, as described in Chapter 17, it may be within the capability of an educational system—probably with the complicity of broader social trends—to put a ceiling on, or actually dampen, the realized intelligence of those with high potential.

30

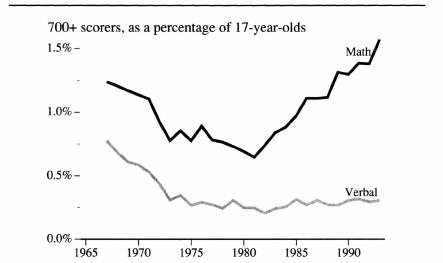

One more piece of the puzzle needs to be put in place. The SAT population constitutes a sort of broad elite, encompassing but not limited to the upper quartile of the annual national pool of cognitive ability. What has been happening to the scores of the narrow elite, the most gifted

students—roughly, those with combined scores of 1400 and more—who are most likely to fill the nation’s best graduate and professional schools? They have gone down in the Verbal test and up in the Math.

The case for a drop in the Verbal scores among the brightest can be made without subtle analysis. In 1972, 17,560 college-bound seniors scored 700 or higher on the SAT-Verbal. In 1993, only 10,407 scored 700 or higher on the Verbal—a drop of 41 percent in the raw number of students scoring 700 and over, despite the larger raw number of students taking the test in 1993 compared to 1972.

31

Dilution of the pool (even if it were as real as legend has it) could not account for smaller raw numbers of high-scoring students. But we may make the case more systematically.

The higher the ability level, the higher the proportion of students who take the SAT At the 700 level and beyond, the proportion approaches 100 percent and has probably been so since the early 1960s (see Chapter 1). That is, almost all 17-year-olds who

would

score above 700 if they took the SAT do in fact take the SAT at some point in their high school career, either because of their own ambitions, their parents’, or the urging of their teachers and guidance counselors. It is therefore possible to think about the students who score in the 700s on the SAT as a proportion of all 17-year-olds, not just as a proportion of the SAT pool. We cannot carry the story back further than 1967 but the results are nonetheless provocative, as shown in the next figure.

32

The good news is that the mathematics score of the top echelon of American students has risen steeply since hitting its low point in 1981. Given all the attention devoted to problems in American education, this finding is worth lingering over for a moment. In a period of just twelve years, from 1981 to 1993, the proportion of 17-year-olds scoring over 700 on the SAT-Math test increased by 143 percent. This dramatic improvement during the 1980s is not explainable by any artifact that we can identify, such as having easier Math SAT questions.

33

Nor is it due to the superior math performance of Asian-American students and their increase as a proportion of the SAT population. Asian-Americans are still such a small minority (only 8 percent of test takers in 1992) that their accomplishments cannot account for much of the national improvement. The upward bounce in the Math SAT from 1981 through 1992 was a robust 104 percent among whites.

34

Now let us turn to the less happy story about the SAT-Verbal. The proportion of students attaining 700 or higher on the SAT fell sharply from 1967 to the mid-1970s. Furthermore, SAT scores as of 1967 had been dropping for four years before that, so we start from a situation in which the verbal skills of America’s most gifted students dropped precipitously from the early 1960s to the early 1970s. Unlike the Math scores, however, the Verbal scores did not rebound significantly. Nor may one take much comfort from the comparatively shallow slope of the decline as it is depicted in the figure. The proportional size of the drop was large, from about eight students per 1,000 17-year-olds in 1967 to three per 1,000 in 1993, a drop of about 60 percent.

35

The other major source of data about highly talented students, the Graduate Record Examination, parallels the story for the students scoring 700 or above on the SAT.

36

Among the most gifted students, there is good news about math, bad news about verbal

Source:

The College Board.

How might these disparate and sometimes contradictory trends be tied together?

One important part of the story begins with the 1950s. Why didn’t the scores fall, though the proportion of students taking the SAT went from a few percent to almost a third of the high school population in

little more than a decade? The answer is that the growing numbers of SAT takers were not students with progressively lower levels of academic ability but able students who formerly did not go on to college or went to the state university (and didn’t take the SAT) and now were broadening their horizons. This was the post-World War II era that we described in Chapter 1, when educational meritocracy was on the rise. As the path to the better colleges began to open for youngsters outside the traditional socioeconomic elites, the population of test takers grew explosively. During this period, we can safely assume that the pool opened up to new socioeconomic groups, but it occurred with no dilution of the pool’s academic potential, because the reservoir of academic ability was deep. Then, as the 1950s ended, another factor worked to sustain performance: From the

Sputnik

scare in 1957 through the early 1960s, American education was gripped by a get-tough reform movement in which math and the sciences were emphasized and high schools were raising standards. Education for the college bound probably improved during this period.

Then came the mid-1960s and a decade of decline. What happened to education during this period has been described by many observers, and we will not recount it here in detail or place blame.

37

The simple and no longer controversial truth is that educational standards declined, along with other momentous changes in American society during that decade.