The Betrayal (43 page)

Authors: Kathleen O'Neal Gear

As Pappas Silvester strode down the brazier-lit palace hall, he nervously tugged at his collar; his neck felt swollen, his collar too tight. His fingers came back slick with sweat. He passed several soldiers on guard. Not one looked at him. He might have been a distant insect to them, barely visible.

The deeper he went into the palace, the more the endless columns below the high-arched vaults resembled cold stalagmites. He swore he felt the touch of evil. He had always felt it here, in Constantine's palace. The air grew cold and sinisterly damp. Behind every shadow there lurked a presence, like a living thing, whispering to itself in the darkness.

Or it could have simply been his own fear. At the moment it was slithering around his belly, making him ill.

He rounded a corner, and stopped. At the end of the hall, in front of Constantine's chamber, stood four centurions. That was ⦠odd. There were always sentries, but he almost never saw men of this rank, or at least, not this many, gathered just outside the emperor's door.

As he walked toward them, the centurions turned.

“A pleasant evening to you, Centurion Felix.” Silvester dipped his head. “And Pionius, how are you?” The other two officers, he did not know.

Pionius, a tall, dark-haired man with burly shoulders, answered, “I am well, Pappas. He's waiting for you.

Been

waiting for you. For some time.”

Been

waiting for you. For some time.”

In a faintly shrill voice, he cried, “I was only just informed he'd requested me! I hope he's not annoyed.”

Pionius extended a hand to the door. “See for yourself.”

Pionius and the other officers walked away down the hall, talking in low voices.

Silvester squared his shoulders and, in a small voice, called, “Your Excellency? It's Silvester.”

“Enter.”

The word carried no hint of anger, which relieved Silvester. He pushed open the heavy door and walked into the chamber.

The emperor sat behind his table, heaped with maps, reading some missive. His brow was furrowed distastefully. He wore a dark blue capeâthreaded through with silver and goldâover a scarlet robe. His sword belt lay across the back of a nearby chair. Easily within reach.

Silvester patiently waited to be recognized. The fire in the hearth cast a flickering amber gleam over the ornately carved furniture and the vaulted ceiling.

Without looking up, Constantine inquired, “Did they find it?”

“Well ⦠er, no. Not exactly.”

Constantine's gaze slowly lifted. His eyes were like oiled metal, shiny and hard, capable of ringing eternal darkness. “Answer me.”

Silvester flapped his arms against his sides. “Pappas Meridias informed me that they

did

find a tomb with an ossuary marked

Yeshua bar Yosef,

butâ”

did

find a tomb with an ossuary marked

Yeshua bar Yosef,

butâ”

“And, as I instructed, it was destroyed.”

Silvester ran his fingers around his collar again. It was strangling him. “No.” He rushed to add, “Because we could not be certain it was

the

ossuary. Pappas Macarios claimed to have

two

more such ossuaries in his office! Apparently the name was extremely common during the time our Lord lived. So, you see, the tomb is no threat to us. We can't prove it is his burial, but

no one else

can prove it either.”

the

ossuary. Pappas Macarios claimed to have

two

more such ossuaries in his office! Apparently the name was extremely common during the time our Lord lived. So, you see, the tomb is no threat to us. We can't prove it is his burial, but

no one else

can prove it either.”

Constantine toyed with the missive on his desk, then tossed it aside and stood up. He reached for his sword belt and strapped it on. As he came around the table, Silvester's soul shriveled to nothingness. He had always known that death awaited him here, in this chamber.

Constantine stopped before him, propped his hands on his hips, and said, “I still want the tomb covered over with earth. Bury it deep.”

“Yes, Excellency. I'll send word to Pappas Macarios immediately.”

Constantine swayed slightly on his feet, as though he'd drunk too much wine while conferring with his centurions.

But when he looked down, there was no hint of drunkenness. The eyes that burned into Silvester were the eyes of an emperor who was at heart also a beast. They were not quite human.

“Silvester, I have spoken with my

strategoi,

my generals, and they agree with me that Christianity, as we have created it, may be the most powerful imperial tool in the history of the empire.”

strategoi,

my generals, and they agree with me that Christianity, as we have created it, may be the most powerful imperial tool in the history of the empire.”

Silvester blinked his confusion. “Excellency?”

“The religion is spreading like a raging forest fire.”

“Oh, well, yes, Excellency!” Silvester replied, suddenly excited. “Of course, it is! The Truth is like a rare pearlâ”

“If we are careful to control and direct the Faith, it will be very useful.” He swayed on his feet again, perhaps from exhaustion. “That shouldn't be too difficult now, should it? Without a body, the resurrection is safe.”

123

123

“Well ⦠we still have enemies. Pappas Eusebios is an advocate of tolerance. He will never willingly submit to our hard-line dogmas. And Pappas Macarios in Jerusalem almost certainly helped the Heretic and his band of thieves. Heâ”

“There will always be those who oppose us. But when we are finished, only

our

version of the Truth will remain. And, Silvester, I guarantee you, in the end, there will be only

one

pappas of the Church, and he will be in Rome.”

our

version of the Truth will remain. And, Silvester, I guarantee you, in the end, there will be only

one

pappas of the Church, and he will be in Rome.”

The veiled promise that Silvester would one day lead all of Christendom sent a heady rush through him. “But why Rome, Excellency? The other bishops will not be happy.”

Constantine turned his back on Silvester and returned to his chair. As he sat down, he extended his hand, palm up, then suddenly closed it to a crushing grip, and hissed, “The Church

will

be mine.”

will

be mine.”

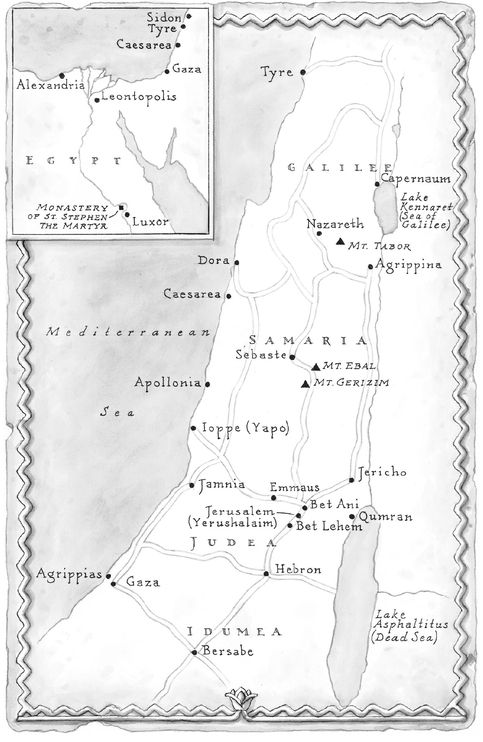

With one exception,

Jerusalem,

we use the correct historical names for biblical places and characters like Jesus, Mary, Joseph, and Johnâwhich means we use the names they would actually have been called by at the time. Many of the names are obvious. For example,

Markos

and

Loukas

were clearly the figures we know as “Mark” and “Luke.”

Bet Lehem

and

Bet Ani

are “Bethlehem” and “Bethany.” Other proper names, however, are not so obvious. Hopefully, this glossary will alleviate some of the confusion associated with the more unfamiliar names.

Jerusalem,

we use the correct historical names for biblical places and characters like Jesus, Mary, Joseph, and Johnâwhich means we use the names they would actually have been called by at the time. Many of the names are obvious. For example,

Markos

and

Loukas

were clearly the figures we know as “Mark” and “Luke.”

Bet Lehem

and

Bet Ani

are “Bethlehem” and “Bethany.” Other proper names, however, are not so obvious. Hopefully, this glossary will alleviate some of the confusion associated with the more unfamiliar names.

Please keep in mind that though scholars suspect some of the original gospels may have been written in Hebrew or Aramaic, the extant New Testament documents were written in the Greek language, which means the original Hebrew or Aramaic names of people like

Yeshua

(Jesus) and

Yakob

(James) were translated into Greek as

Iesous

and

Iakobos.

Yeshua

(Jesus) and

Yakob

(James) were translated into Greek as

Iesous

and

Iakobos.

Lastly, in Greek there is no

sh

sound, and in Hebrew and Aramaic there is no

j

sound. As well, Hebrew and Aramaic are written almost entirely without vowels. These unique features of the languages have led to many spelling variations over time, as can be seen in the following.

sh

sound, and in Hebrew and Aramaic there is no

j

sound. As well, Hebrew and Aramaic are written almost entirely without vowels. These unique features of the languages have led to many spelling variations over time, as can be seen in the following.

Â

Galilee

In Hebrew it was referred to as the

Galil.

In the original Greek New Testament it was called the

Galilaian.

Galil.

In the original Greek New Testament it was called the

Galilaian.

Â

James

In Hebrew and Aramaic his name was

Ya'akov,

or

Yakob

(Jacob). In Greek it was

Iakobos,

and in Latin,

Iacomus,

which when translated into the Germanic spelling became

Jacomus,

then in Spanish

Jaime.

Finally, because the King James version translated it as

James

in 1611, it has remained

James

ever since in English translations.

Ya'akov,

or

Yakob

(Jacob). In Greek it was

Iakobos,

and in Latin,

Iacomus,

which when translated into the Germanic spelling became

Jacomus,

then in Spanish

Jaime.

Finally, because the King James version translated it as

James

in 1611, it has remained

James

ever since in English translations.

Â

Jerusalem

Hebrew:

Yerushalaim

. Greek:

Ierosoluma.

We mention the Greek here only for the sake of historicity. From this point on, in the chapters set in the fourth century, you will read “Jerusalem.” We have made this concession because we think the English name helps to better anchor English readers to the place and time.

Yerushalaim

. Greek:

Ierosoluma.

We mention the Greek here only for the sake of historicity. From this point on, in the chapters set in the fourth century, you will read “Jerusalem.” We have made this concession because we think the English name helps to better anchor English readers to the place and time.

Â

Jesus

His name was

Yeshua

in Hebrew, or in more formal situationsâfor example, in the Jerusalem Templeâ

Yehoshua

. However, because the first-century dialect of Galilee dropped the final letter (

ayin

), Yeshua's Galilean friends, or those who were very close to him, probably called him by the name

Yeshu.

As well, early rabbinic sources largely use

Yeshu

for “Jesus of Nazareth,” and the Talmud

only

uses

Yeshu

for “Jesus of Nazareth.”

Yeshua

in Hebrew, or in more formal situationsâfor example, in the Jerusalem Templeâ

Yehoshua

. However, because the first-century dialect of Galilee dropped the final letter (

ayin

), Yeshua's Galilean friends, or those who were very close to him, probably called him by the name

Yeshu.

As well, early rabbinic sources largely use

Yeshu

for “Jesus of Nazareth,” and the Talmud

only

uses

Yeshu

for “Jesus of Nazareth.”

In Greek his name was

Iesous,

or

Iesous Christos,

which we translate into English as “Jesus” or “Jesus Christ.”

Iesous,

or

Iesous Christos,

which we translate into English as “Jesus” or “Jesus Christ.”

Â

Jews

Hebrew:

Yehudim.

Greek:

Ioudaiosoi.

Yehudim.

Greek:

Ioudaiosoi.

Â

John

The Hebrew is

Yohanan.

Greek:

Ioannes.

Yohanan.

Greek:

Ioannes.

Â

Joseph

Hebrew:

Yosep, Yosef,

or in more formal situations,

Yehosef.

In the Greek manuscripts there is a great deal of variance:

Ioses, Iose, Iosetos, Ioseph.

Many scholars believe that the form

Ioses

follows the Galilean pronunciation of the Hebrew

Yosep.

Yosep, Yosef,

or in more formal situations,

Yehosef.

In the Greek manuscripts there is a great deal of variance:

Ioses, Iose, Iosetos, Ioseph.

Many scholars believe that the form

Ioses

follows the Galilean pronunciation of the Hebrew

Yosep.

Â

Mary

Miriam

in Hebrew. In Aramaic it became

Maryam,

and in Coptic it was

Mariham.

The New Testament Greek gospels call her

Maria

or

Mariam.

in Hebrew. In Aramaic it became

Maryam,

and in Coptic it was

Mariham.

The New Testament Greek gospels call her

Maria

or

Mariam.

Â

Matthew

In Hebrew it is

Matthias, Mattiyahu,

or

Matya.

The Greek is

Maththaios.

Matthias, Mattiyahu,

or

Matya.

The Greek is

Maththaios.

NORTH AMERICA'S FORGOTTEN PAST SERIES

Â

People of the Wolf

People of the Fire

People of the Earth

People of the River

People of the Sea

People of the Lakes

People of the Lightning

People of the Nightland

People of the Silence

People of the Mist

People of the Masks

People of the Owl

People of the Raven

People of the Moon

People of the Weeping Eye

People of the Thunder

(forthcoming)

People of the Fire

People of the Earth

People of the River

People of the Sea

People of the Lakes

People of the Lightning

People of the Nightland

People of the Silence

People of the Mist

People of the Masks

People of the Owl

People of the Raven

People of the Moon

People of the Weeping Eye

People of the Thunder

(forthcoming)

Â

People of the Dawnland

Â

Â

THE ANASAZI MYSTERY SERIES

Â

The Visitant

The Summoning God

Bone Walker

The Summoning God

Bone Walker

Â

Â

BY KATHLEEN O'NEAL GEAR

Â

Thin Moon and Cold Mist

Stand in the Wind

This Widowed Land

It Sleeps in Me

It Wakes in Me

It Dreams in Me

Stand in the Wind

This Widowed Land

It Sleeps in Me

It Wakes in Me

It Dreams in Me

Â

Â

BY W. MICHAEL GEAR

Â

Long Ride Home

Big Horn Legacy

The Morning River

Coyote Summer

Athena Factor

Big Horn Legacy

The Morning River

Coyote Summer

Athena Factor

Â

Â

OTHER TITLES BY KATHLEEN O'NEAL GEAR AND W. MICHAEL GEAR

Â

Dark Inheritance

Raising Abel

The Betrayal

Children of the Dawnland

Raising Abel

The Betrayal

Children of the Dawnland

Â

Other books

Hometown Love by Christina Tetreault

Wag the Dog by Larry Beinhart

Grudging by Michelle Hauck

Daemon Gates Trilogy by Black Library

Stepping Up To Love (Lakeside Porches 1) by Katie O'Boyle

Claimed by Cartharn, Clarissa

Wifey 4 Life by Kiki Swinson

Midnight Sun by Jo Nesbo

A Mersey Mile by Ruth Hamilton

Force Out by Tim Green