Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (28 page)

One such method of confession-extracting torture was called ‘kneeling on chains’. The prisoner’s thumbs and big toes were bound together, behind their back, forcing the entire weight of their kneeling body to fall on the toes and knees. As if this weren’t uncomfortable enough, a coil of sharp-edged chain was placed under the suspect’s knees, inflicting excruciating pain and lacerating the knees, sometimes cutting so deep that it severed the tendons. If it was allowed to continue long enough, permanent damage would be done to the knee joints.

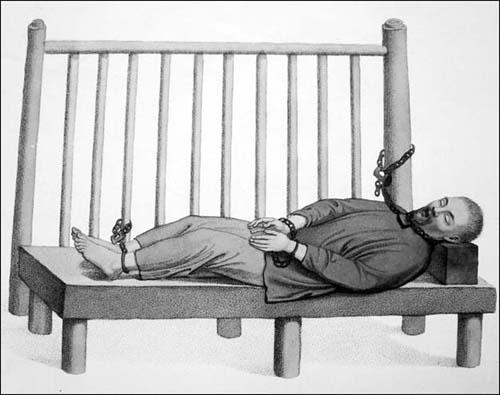

Even if such torture was not employed, a few days, or weeks, in a Chinese jail should have been enough to loosen the tongue of even the most recalcitrant prisoner. While prisoners were allowed to roam free in communal cells during the day, at night each man was locked into their bunk with a device nearly identical to the stocks. The prisoner was laid on their back, on their bunk, and their feet were locked in a stock-like device attached to the foot of the bed, making it impossible for the prisoner to shift position or turn over in their sleep. Just to make sure the victim did not, somehow, wriggle out of the stocks, their hands were locked in manacles attached to the wall with chains and another chain, attached to the bunk, was pulled tight across their chest and locked into place. There are no accounts of prisoners escaping from Chinese jails during the night.

When a confession was finally elicited and sentence had been duly passed, lesser crimes were often punished by the imposition of a fine, as they were in most other societies. In China, however, this fine might well be accompanied by a loss of social rank. In instances of petty crime, this loss of position might only be temporary; for more serious offences it could be permanent. If the judge considered a fine or loss of rank too severe a punishment, the guilty party might simply have their ears twisted. Two burly guards held the prisoner immobile while grabbing his ears and twisting with all their might; not hard enough to tear the flesh, but certainly hard enough to leave a lasting impression. For slightly more serious offences such as petty theft, public drunkenness or insulting someone of a superior social rank, a good flogging might be imposed and this was always carried out immediately – in the courtroom. To determine the proper number of blows, the judge again referred to the Tang Code. The crime might call for the use of a light whip or a heavy whip and could, depending upon the nature and circumstances of the incident, demand anywhere from 10 to 100 blows. The punishment must precisely fit the crime. When the severity of the flogging had been determined, the punishment was inflicted with a whip made of lengths of split bamboo. While it may not have broken the skin, enough pain and damage were inflicted that the prisoner’s entire back and rump were soon a mass of subcutaneous blood-blisters.

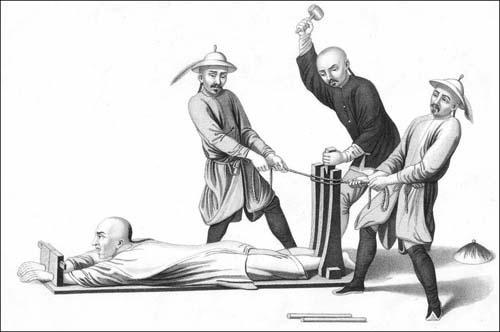

The Chinese punishment of ‘kneeling on chains’. Although not precisely an image of what is described in the main body of the text, this beautifully rendered painting should serve to illustrate the sort of punishment being described.

Here we see a Chinese version of the prison cell. Whether attempted escapes were commonplace is unknown, but this prisoner has been secured by wrist, ankle and neck to his cell bunk, which was also presumably contained behind some sort of locked door or cage and would have had armed guards as well.

One possible alternative to a sound whipping was for the convict to be forced to wear a pillory-like collar known alternatively as the

fcan hao, cangue, tcha

and

ea

. Like the European pillory, this device consisted of a massive wooden collar into which the victim’s head was locked. In this case, however, the collar was not mounted on a stake. Rather, it was just a chaffing, cumbersome collar the prisoner was forced to wear for a proscribed period of time. To make the punishment even more uncomfortable, the outer rim of the collar was sometimes fitted with three iron spikes, making it impossible for the condemned to lie down or rest his head. Generally, if someone did something which warranted being locked into this collar, they had also been bad enough to receive a flogging; so they were first whipped and then pilloried.

As a vast country populated by people who spoke many different languages, translators were an integral part of Chinese society. For interpreters who knowingly mistranslated either their boss’s words, or those of another party, a special punishment was devised. The convict was forced into a kneeling position with a thick bamboo rod placed behind their knees. When their knees were on the ground and their full weight on the bamboo rod, a guard would stand on either end of the rod. The pain was excruciating but no permanent, physical damage was inflicted. Special punishment was also reserved for women convicted of the crime of ‘lack of modesty’ – a polite way of saying prostitution. For this particular crime, the prisoner was forced to kneel while small slivers of wood were placed between her fingers. Heavy cord was then wrapped around the fingers and drawn tighter and tighter, forcing the knuckle bones against the wood. Note that during the majority of these punishments the prisoner was made to kneel. This subservient posture not only showed deference for the judge, but was yet another form of humiliation inflicted on the guilty party.

This image comes from a twentieth-century postcard of Chinese prisoners of war wearing the cangue, which served very much like a portable version of the European pillory.

No matter what form the punishment was to take it was customary, in this highly ritualistic society, for the prisoner to grovel before the judge – on their knees, of course – and beg for forgiveness, under-standing and leniency. Whether or not this ceremonial display of repentance had any effect on either the court or the sentence is open to debate but there are instances where the prescribed sentence would undoubtedly have brought even the most hardened criminal to the point of begging. One of the most shocking, non-capital crimes in old China was reserved for Buddhist monks convicted of having sexual relations. There was only one punishment for this crime. A hot iron rod was driven through the neck muscles of the victim and a length of chain was then threaded through the raw, charred hole and tied around his neck. Like a dog on a horrible leash the monk was led through the streets of town, naked, begging for money. Only when a court-specified amount of cash had been collected was the poor wretch released and returned to his monastery. There were even harsher, non-capital punishments, one of the more common being blinding. The condemned was held down while a guard rubbed their eyes with a cloth soaked in lime. In a matter of minutes the eyes were entirely eaten away.

In addition to covering a myriad of lesser civil and criminal offences the Tang Code also dictated the nature of, and punishment for, what was known among the Chinese as ‘abominable crimes’. There were only ten of these but the terms in which they were couched allowed a fair amount of latitude in determining exactly what acts might constitute an abominable crime. According to the Code, these crimes included: plotting rebellion, plotting sedition, plotting treason, resistance to authority, depravity, great irreverence, lack of respect for a parent, discord, unrighteousness and incest. In the first case, plotting rebellion, simply being involved in discussions with other rebels was sufficient for conviction. For the next two offences, the seditious or treasonous act must actually have taken place for the accused to be found guilty. For all three crimes, decapitation was the only possible punishment but the sentence did not end there. Under the assumption that such dastardly plots are never carried out alone, a person found guilty of one or more of these offences was also assumed to have confided their plans to their relatives and household. Consequently, a collective punishment was inflicted on the condemned man’s family. His father and sons over fifteen years of age were strangled; younger sons, brothers, grandfathers, concubines and servants were sold as slaves and all female relatives were driven into exile. A similarly grim, collective fate was visited on the extended family of anyone convicted of murdering three or more members of their family.

This nineteenth-century engraving was one of the earliest depictions of Chinese justice to which Western Europe was exposed. It would have probably seemed a cruel and barbaric torture to nineteenth-century Western civilization who had moved on to imprisonment and penal reform.

Because the family unit was so central to the Chinese way of life, crimes against the family were considered as heinous as crimes against the government; it was an affront to the natural order of things and therefore must be punished by the harshest means possible. Plotting to kill one or both parents, or either grandfather, was punishable by death, as was the act of striking a parent. In fact, if a child wrongly accused a parent of a criminal act the child was put to death for their audacity. Even if the accused parent was subsequently convicted of the crime, the child was sentenced to 100 blows with a heavy whip and three years in prison for exposing their parent’s dishonour. Curiously, because familial order could only be maintained when children obeyed their parents, hitting a child, or turning them in for the commission of a crime, was not considered a punishable offence. As harsh as this all sounds, the Tang Code did make exceptions. Punishment for crimes against the family was always less severe and sometimes suspended altogether when the convicted party was under seven years of age, or over ninety. Those between seven and fifteen and those between seventy and ninety were exempt from torture and physical punishment, and could redress all but the most severe crimes by paying a fine. The mentally and physically handicapped were exempt from all forms of torture and those who were the sole support of aged or physically handicapped parents often had their sentences commuted so the parents were not made to suffer for their children’s crimes.