The Black History of the White House (16 page)

Read The Black History of the White House Online

Authors: Clarence Lusane

Unfortunately, two unexpected events foiled the well-planned plot. First, after traveling about 150 miles, the boat ran into bad weather and was forced to anchor at Cornfield Harbor, near the end of the Maryland peninsula. The delay was not welcome, but even under those circumstances the

Pearl

had enough of a head start that a few hours should not have made a difference as long as the escape and its intended route remained undiscovered.

However, a betrayal of epic proportion was unfolding back in Washington, D.C. Although contemporary reports mentioned other individuals, most later researchers believe that Judson Diggs, a free black man, had informed a posse of slave

hunters that the escaping blacks were on the

Pearl

and which direction it had headed. Whether it was out of fear, revenge against a woman on the boat who reportedly had jilted him, or for moneyâall three reasons have been suggestedâDiggs's treachery goes down in history as one of the worst betrayals of the antebellum period. Apparently, slave catchers initially believed that the slaves had escaped on foot and were weaving their way north, the exact opposite direction from the way the

Pearl

was headed.

24

Soon, on the information provided by Diggs, a steamboat set out and seized the

Pearl

and everyone on board while the boat was still anchored.

Drayton and Sayres were charged with larceny, and all the black individualsâ enslaved and freeâwere unceremoniously marched through the streets of Washington, D.C. and caged in slave pens. White enslavers and their supporters in Washington, D.C. were so incensed that they wanted to drag Drayton and Sayres out of jail and have them executed on the spot. While a few of the captured blacks were taken back by their owners, most were being prepared to be sold South, where the merciless cruelty of slave breakers was renowned. Of the eleven members of the Bell family that were captured on the

Pearl

, only Mary and her youngest son Thomas were purchased by family and supporters, the rest were bought and re-enslaved. The six Edmonson siblings were all bought, re-enslaved and sent South. “Among those sold were people who were legally free,” writes G. Franklin Edwards and Michael R. Winston in an article featured on the White House Historical Society website.

25

The White House of President James Polk found itself in a tight spot, endeavoring to prevent riots from breaking out as news of the white-assisted escape spread. More out of political self-interestâit would have been disastrous to have a race riot in Washington, D.C. during an election yearâbut his sympathies

lying with his fellow white enslavers, President Polk sought to quell the mobs in the streets and reluctantly sent troops to protect the offices of the abolitionist

National Era

newspaper from being destroyed.

26

One ironic link is that in 1845, just two years before Paul Jennings achieved his liberation, Dolley Madison had earned herself a little money by renting him out to President Polk.

27

Though the escape of 1848 was foiled, it generated a nationwide movement to defend and free both the blacks and the whites who were involved. Abolitionist forces mobilized education campaigns, raised funds, and put together a legal team that included Horace Mann, then a congressman who had succeeded relentless antislavery advocate John Quincy Adams and later became famous as an educator. They also received support from

Uncle Tom's Cabin

author Harriet Beecher Stowe, and a massive effort was mounted to obtain a pardon from President Millard Fillmore.

For their part in the attempted escape, Drayton and Sayres spent four years in prison before receiving an executive pardon from President Fillmore on August 11, 1852. Larceny charges had been dropped, but Sayres was convicted on the charge of illegal importation of slaves.

28

Drayton remained defiant, however, even after being released from prison. Criticizing the racism of slavery, he wrote:

By my actions, I protested that I did not believe that there was, or could be, any such thing as a right of property in human beings. Nobody in this country will admit, for a moment, that there can be any such thing as property in a white man. The institution of slavery could not last for a day, if the slaves were all white. But I do not see that because their complexions

are different they are any less men on that account. The doctrine I hold to, and which I desired to preach in a practical way, is the doctrine of Jefferson and Madison, that there cannot be property in manâno, not even in black men.

29

To reference Madison was a sardonic nod to one of the unacknowledged leaders of the escape attempt, who had been enslaved by the president.

Miraculously, Jennings's involvement went undetected. One report stated that Jennings had originally planned to be on the

Pearl

but had had a change of heart at the last minute when he realized that doing so would violate his contract with Websterâan agreement he was committed to honoring. This account notes that Jennings actually left a letter to Webster stating he was leaving out of a “deep desire to be of help to my poor people.”

30

However, as historian Mary Kay Ricks points out, more likely Jennings did not board the

Pearl

because it was unnecessary for a free man to put himself at risk when he could meet the ship almost anywhere it landed. Furthermore, unlike Edmondson and Bell, he did not have family aboard the ship.

Jennings may have gone into hiding after the capture of the

Pearl

. If he did, it was not for long, because he was active in the effort to help those who had been captured. His ability to remain free also indicates that if there was a betrayal, the person or persons involved either did not know of Jennings's involvement or for some unknown reason did not implicate him. Jennings helped to raise money in an attempt to buy and free some of those captured, and thus avoid having them sent South, but the funds raised did not suffice.

31

Eventually finding work at the Department of the Interior,

Jennings lived to experience the liberation of black people from slavery. He was seventy-five years old when he died in Washington, D.C., in 1874.

Paul Jennings's White House story, in literal and literary forms, is a remarkable one of willpower, honor, sacrifice, courage, activism, and risk in the name of black freedom. His legacy was passed on for generations, and in a noteworthy circle of historic completion, dozens of his descendants returned to the White House for a reunion in August 2009 to honor his role in U.S. history.

32

As part of their visit, they viewed the famous Stuart painting of George Washington. More important, they came to acquaint themselves with the place where their great-great-great-grandfather had lived enslaved by the fourth president of the United States, and to honor his bravery and boldness, along with that of the many undocumented others who, at great personal peril, did all they could to liberate black people from their bondage to white enslavers. In a sense, it was Jennings and the countless others in the underground networkâby their rebellions and the actions they took to free the nation from the atrocities of human trafficking and enslavementâwho were the true vanguard of Madison's founding vision of a democratic and liberated nation.

The White House Becomes Whiter

[T]he city was light and the heavens redden'd with the blaze.

âAn eyewitness description of the burning of the White House.

33

It took three years to rebuild the White House and the other public buildings in Washington, D.C. that had been destroyed by the British invasion. President James Monroe, another Virginian who enslaved dozens of blacks, would formally open the doors of the White House to the public on January 1, 1818. The building had been burnt to a shell, and it required massive work to restore its original structural integrity and appearance. Much of the surviving architecture had to be demolished. For political reasons, however, Monroe and Congress publicly contended that “repair” rather than “reconstruction” was occurring. This deception was facilitated by cheaply substituting timber for bricks “in some of the interior partitions,” which would eventually require key parts of the White House to be rebuilt again between 1948 and 1952.

34

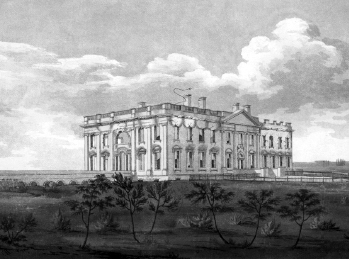

View from northeast of the damaged White House after the British army looted and burned it on August 24, 1814.

Enslaved black people, in full view of the White House and Congress, continued to toil side by side with free workers to rebuild the nation's capital. It is unclear, however, exactly how many blacks worked on the White House and other D.C. structures that had been damaged by the British attacks. Historian William Seale argues that the growth of capitalism in the United States dramatically changed the nature of the rebuilding

compared to the original construction operations. Work done in the 1790s involved many individuals contracting with builder James Hoban, including both free and enslaved blacks. This time, however, instead of one builder dominating, operations opened up to many “manufacturers, merchants, suppliers, contractors, and other businessmen.”

35

Seale estimated that approximately 60 of the 190 men that were hired in the summer of 1817, when the main work was being finished, were enslaved black men who had been rented out by their owners.

36

It is not known exactly what work they performed, nor how many, if any, of the other 130 or so other men were free blacks. It is probably safe to assume that slave labor was also used during the 1815â1816 period, when a great deal of the demolition and trash removal was carried out.

As discussed in Chapter 3, the Capitol, to the east of the burned out White House, also had to be rebuilt. The two sites were linked by the area now known as the national mall, but which then served as a bustling marketplace for human traffickers. From either the legislative or the executive buildings of the U.S. government, one could look out the window any day of the week and see hundreds of poorly dressed, desperate individuals locked in chains, their lamentations and wails impossible to ignore as they were being beaten, forced to march while manacled to others, and sold off on an auction block. That this powerful daily reminder of white people's barbarity toward black people existed in clear sight of advocates for a more inclusive and democratic society surely must have fired the determination of abolitionists in Congress who fought to end, erode, or limit slavery through legislative means. For the most part, they did not get support from the White House while it was in the charge of slave-owning and slavery-enabling presidents.

A New White House Era

The physical reconstruction of the White House also symbolized a transition in the nation's racial politics. Monroe would represent the last generation of Revolutionary War presidents. The debate over slavery's expansion, increasing slave rebellions, and the aggressive abolition movement would force president after presidentâuntil Lincolnâto confront the issue, but each would compromise and procrastinate rather than implement a permanent solution. With each passing year, public intolerance of enslavement intensified, driving the country closer and closer to armed conflict.

Of the eleven U.S. presidents between Madison and the beginning of the Civil War, seven enslaved black peopleâpresidents James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, James Knox Polk, and Zachary Taylorâand five of them enslaved blacks at the White HouseâMonroe, Jackson, Tyler, Polk, and Taylor. Four U.S. presidents during this periodâJohn Quincy Adams, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchananâdid not own slaves either in or outside of the White House, but, as the records show, they did very little as president to end the institution. In the main, rather than undergoing a gradual erosion as many of the founders whimsically hoped, slavery expanded westward, and the political divisions over buying, selling, breeding, and trafficking black people escalated and turned increasingly violent.

In 1812, there were nine slave states and nine “free” states, where slavery was legally abolished but where whites (if they technically lived in other states) were permitted to bring the blacks they enslaved. The “free” states were Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont; the slave states were

Delaware, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia.

Washington, D.C., then as now, was not a state. Slavery was legal in the city and even so-called free blacks faced severe civil, political, economic, and social restrictions on their freedom. At various times between 1800 and the end of the Civil War, free blacks in D.C. were “legally barred from the streets after 10:00 p.m. . . . required to register and carry a certificate of freedom . . . required to post a $500 bond guaranteed by two white men . . . barred from the Capitol grounds unless present there on business; and . . . barred from owning most types of small businesses.”

37