The Bolter (36 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

Rosita, Arthur, Idina, and Precious left for Rwanda, where, as Rosita describes in her book

Appointment in the Sun

,

8

they climbed up into the forests and installed themselves in a government rest house to wait for the sighting of a gorilla. After a few evenings the news came that one had been heard crashing through the forest. They set off at dawn, much to Rosita’s disquiet, unarmed apart from a single rifle that “looked suitable for peppering rooks … So stringent were the regulations against killing the rare gorilla that the hundreds of spear men acting as beaters were warned not to use their weapons, except as a last desperate measure in self-defence.” As they scrambled deeper into the forest a Belgian official warned them not to move if a gorilla charged them, “Then he may not kill you.” By the time their party had caught up with the rustling bushes, Rosita was terrified.

The expedition proved worth it. “The branches parted. Out came a delicious shaggy creature on all fours about the size of a Shetland pony. It looked kind and soft” and was followed by two babies, “exactly like nursery toys.” Then, suddenly, the father appeared: “a great silver-streaked male… stood upright and glared at us, beating his breast.” The four friends, obeying instructions, froze until, a few moments later, the silverback “dropped and shambled after his family.”

After the gorillas they went deep into the Congo jungle, to meet a pygmy tribe. Finding the tribe was easy enough but the people were shy of the strangers and kept disappearing into the trees until Idina, even though deep in the jungle, somehow “produced ice out of a thermos bottle.” One of the men stopped to watch. Idina gave him a fragment of ice. “He dropped it as if it had been a live coal. But when he saw that we handled it with safety, he put it very carefully between two

leaves and left it in the sun.” Half an hour later it had vanished. The poor man fled “gibbering, into the tree depths.”

That evening, back at their government rest house, “an inn consisting of a whole family of huts, large and small” in the depths of the jungle, the party bumped into the society millionairess Edwina Mountbatten—the future Vicereine of India—and her reputedly bisexual sister-in-law, Lady Milford Haven. They were accompanied by a man known as Buns Phillips. Edwina had inherited a vast sum of money. Once married, she had embarked on a series of affairs and had now vanished with her sister-in-law for several months. “We sat upon skin rugs and talked unceasingly. Except for our trousers,” wrote Rosita, “it might have been a party in London.” Idina, surrounded by the other women melting and perspiring in the heat, emerged from her hut for the evening looking “as if she had just come out of tissue paper.”

Precious’s company on the trip, however, Rosita noted, had been “rather a nuisance mid-river upon an inadequate raft.” When, on their way back to Kenya, the four travelers reached Uganda, Rosita’s husband left them to fly back home across the Sahara. Idina seized the moment and “discarded Precious,” enabling herself to finish the journey with just Rosita.

In 1918 Idina went to Rosita when she split up from Euan. Now, just over eighteen years later, it was with Rosita there to provide encouragement that she decided that, this time, she would not be defeated by Barbie and would try to see her “darling son” David again. She now had not seen David for almost three years and, although God had been replaced with a passion for Greek culture and history, David’s desire for political revolution had not abated. Whenever David went home he came face-to-face with a world that he believed, quite simply, to be wrong. The year before he had been arrested with two friends for shooting a policeman with an air gun. The shot had come from the windows of the student house they shared in Oxford’s Beaumont Street. They were known as “rather an elite group of Socialists”

9

and the shooting appeared to be a form of protest. The policeman had been only slightly hurt and was therefore capable of telephoning for help. Within minutes, armored cars and the Oxford police force had surrounded the house and the three young men were dragged out in their pajamas at one in the morning. David saw again only too clearly that there was one law for the rich and another for the very rich: they avoided jail and, a few weeks later, he graduated from Oxford with a then extremely rare

First Class degree. He then joined the academic staff of the university, winning a fellowship to go to Greece. In the late spring of 1937 he was living there. Idina obtained his address and wrote to him, suggesting that she visit him. David agreed.

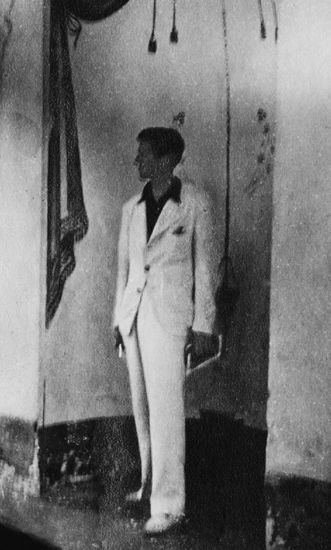

David traveling in Greece

Shortly after returning to Clouds from the Congo, Idina left for Europe. She boarded the Marseille boat at Mombasa, left it at Italy, crossed from Brindisi to Piraeus, and met David in Athens in early May. She bought a car for them to travel in—open-topped for the morning

and evening, with a shade for the middle of the day. They clambered in and drove off.

Side by side in the car with the roof down, they made an unlikely pair. David, never out of thick-rimmed glasses, looked intently serious, and Idina, tiny, bottle-blond, and short-skirted, beside him, looking almost young enough to be his utterly inappropriate wife.

Their first stop was on the coast a few miles south of Athens, where a girlfriend of Idina’s, Balasha, was living with the author Patrick Leigh Fermor, then just twenty-two years old. Their house was a single-roomed water mill and the four of them camped together on the floor. By day they walked around packed local markets, Idina’s short skirt parting the crowd; by night they sat around having what Patrick described as “extremely racy conversations.”

10

It was one thing for Leigh Fermor to watch his girlfriend’s friend talk like that. It must have been quite another for David to watch his mother.

After a week Idina and David left the couple and set off sightseeing. But by the time they had hauled themselves around half a dozen ancient monuments, each miles from the next, in the baking sun, they were at loggerheads.

11

David had inherited every ounce of Idina’s tendency toward headstrong behavior as well as her easy charm, and at times the first could override the second. He still saw the world in stark contrasts of black and white. He refused to take any criticism of Greece and believed his point of view to be the only one viable. Idina had to bite her lip. But she was not always quick enough. The dreams of both of a perfect filial reunion began to evaporate in the heat.

12

As she later wrote to him: “I indeed know what you can be like when you get into one of your bloody moods—it’s hell and there is just nothing one can do.”

13

But something in Idina had changed. Maybe, now that she was forty-four, she was old enough to realize that if she kept moving on, she would reach nowhere. And, in any case, children, unlike husbands, could not be easily replaced. (David’s brother Gee had made it quite clear that he felt his loyalty lay with Barbie and his father and had not come to meet Idina in England.) Whatever it was, this time Idina did not fly away from her fallout with David. Instead she held firm. And, before she left Greece, a month later, she had persuaded her son to come and see his sister, Dinan, when he returned to England later that summer.

Dinan had not had the easiest time staying with her uncle Buck. It appeared that her parity of age with her cousin Kitty had, far from making them best friends, turned them against each other. The Christmas

before, when Buck had taken the family to stay with Avie, Dinan had remained with Avie when the others returned to Fisher’s Gate. The move, it appeared, had been a success. Dinan continued to make frequent trips to Fisher’s Gate to see her cousins in the holidays. For the rest of the time Avie had found a young French governess, Mademoiselle Ida Bocardo, universally abbreviated to Zellée, whom Dinan adored. And, to what must have been both Idina’s comfort and her torment, Avie, who did not have any children herself, was bringing Dinan up as her own daughter. At least Avie was no longer bosom buddies with Barbie, for, when Avie had left Stewart for her new husband, Frank Spicer, the two women had drifted apart.

Idina took David down to Avie’s in August, in the vain hope that he and Dinan might find some bond. It was not obvious. They had met before. Euan and Buck knew each other through politics and Euan occasionally rented Fisher’s Gate from Buck. Buck had also, on two occasions while David and Gee had still been at Eton, persuaded Euan to let the boys come and stay with their cousins and sister (although clearly on the understanding that it would not be during one of Idina’s visits). Buck had even sent his own car and driver to pick the boys up and ferry them back.

Dinan was now a shy eleven-year-old and David a twenty-two-year-old academic. In a group of two rather than six cousins, it was harder to see that they would get on. They had nothing in common apart from a mother they hardly knew. To David, one of five boys and educated in single-sex boarding schools from the age of eight, girls—as it was clear from his encounter in the nursing home with Miss Fenhall—were a foreign species.

Somehow, however, perhaps driven by Idina’s determination now to pull her family together, or swayed by their mother’s delight at seeing the two of them side by side, they managed to find a common ground. As Dinan later said, she had been “very fond” of one of her brothers.

14

And, for the precious couple of days of this visit, Idina had two of her three children with her and could pretend that her life had never kept them apart. She had made mistakes in the past and run from them. Yet here, out of that very past and those very mistakes, were David and Dinan.

AT THE END OF AUGUST

, Idina left for Oggie’s annual house party in Venice. She stayed for a couple of weeks and then wound her way back through Europe, reaching England again at the beginning of October. David had gone back to Greece to pursue his research fellowship, leaving

Idina to spend the next few weeks visiting Dinan and both buying and equipping a car according to a list of detailed instructions that she had extracted from Rosita. And at the end of November, as the temperature in the Northern Hemisphere dropped, Idina persuaded a recently widowed girlfriend, Charlie Dawson, to accompany her, and they drove to Kenya—all the way home.

The two women reached Lisbon alone. There Idina picked up a young man called Emmanuele. After a couple of nights together she asked him whether he felt like driving through the Sahara. He asked if his identical twin might come too. There was, Idina assured him, plenty of room.

The party of four now crossed to North Africa. By the time they reached Alexandria, Emmanuele’s twin had given up all hope of making the same progress with Charlie Dawson that Emmanuele had with Idina, and left. The three of them headed south, camping, as Idina had done with Euan twenty-four years earlier, beneath the emptiness of the vast night skies. And, for Idina, now, the past must have been a relatively sweet place to look back to.

When they reached Kenya, Emmanuele followed her up to Clouds.

A FEW MONTHS LATER

, in the autumn of 1938, David became engaged to a fair-haired, bright-blue-eyed former actress three years older than he. She was the daughter of tin miners turned tea planters, who divided their time between Calcutta and Essex, not far from Frinton. David had, however, met her in the café at the British School at Athens. Her name was Prudence Magor, known as Pru. Expected to follow her older sisters and become a debutante, Pru had run away from home at the age of seventeen to audition for a student place at the Old Vic in London—the theater where John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier were playing their first lead roles. She won a place and called her parents from a telephone box with the news. They were horrified. But Pru was a tough negotiator. Eventually, over the course of the conversation, they agreed to support her if, for the first twelve months, she lodged at the house of a woman they knew in Bayswater—and was home by midnight.

By the time she met David, Pru had toured the world with various theater companies. The countries to which the stage hadn’t taken her, she had taken herself off to—further shocking her parents by working as a salesgirl in dress shops to earn the money for her tickets. She was now living in Athens, studying to be an archaeologist.