The Bolter (38 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

Joss had been murdered.

Idina was at Clouds when she heard the news. She leapt into her car and pounded up the road to Nairobi and into Joss’s bungalow by Muthaiga. The week before, Diana had been wearing the exquisite Erroll family pearls. These were the only heirloom that Dinan might ever receive from her father and Idina did not trust Diana not to steal them. She walked in and searched for the necklace. It was not to be found.

3

Idina returned to Clouds in what must have been a state of both grief and anger. She and Joss had remained friends, seeing enough of each other to keep her affection alive. And she had still been enormously fond of him.

4

Day after day, as she, Ann, and Tom listened to the war news at six o’clock, they heard the latest details of the murder investigation. It was “the only topic of conversation” among visitors to Clouds. The six-year-old Ann asked Idina what had happened. Idina told her that Joss had been driving back from Karen, a suburb of Nairobi, when he picked up a lady in uniform. The lady claimed to suffer from car sickness in the front and asked if she could therefore sit in the back. From there, she shot Joss in the head. Ann asked Idina whether the woman had been caught. Idina replied that she had not been. So, replied Ann, “how do they know that she was carsick in the front?” Idina replied, “I don’t want to talk about it anymore, darling, I am too upset.” This was, of course, in Ann’s view an account invented by Idina, but, she says, “it was such a huge issue that I have never forgotten it.”

Idina was not alone in being upset by Joss’s death. During seventeen years in Kenya, Joss had had affairs with many of the women there, nearly all of whom had retained a soft spot for him. Barely a female eye at Muthaiga was dry. Alice almost immediately again attempted suicide by taking an overdose of pills. And then, fifteen days later, when Idina had hardly had a chance to dry her eyes, she received a cable from Buck that sent her reeling yet further: Euan, too, had died—of stomach cancer.

Euan had been forty-eight—too young to die. And Joss had been even younger: thirty-nine. Unlike the relationship Idina had enjoyed with Joss, there had not been a trace of amiability between her and

Euan since their divorce. Once Idina’s decision to leave him was final, Euan had not wanted to hear her name mentioned again. Married to Barbie, he had started a new life.

Idina, however, had never managed to move on completely. Euan’s photo still sat in her bedroom—a constant reminder of all that she had given up.

Now Euan was dead, taking with him any lingering wonder about what that life might have been. In theory, his death should have closed a chapter for Idina that had been open too long. But he and Joss had been the fathers of her children. All three of them, David, Dinan, and Gee—whom she had not seen for over twenty years—had now become fatherless within a fortnight. Idina, trapped in Kenya by the war, was frustratingly and upsettingly unable to do anything to help them.

Dinan in her early teens

It took another month for the police to make an arrest for Joss’s murder. The story continued to give rise to salacious headlines, about which, back in England, Avie and her husband were doing what they could by carefully cutting them from the newspapers before they reached Dinan at the breakfast table. But Dinan saw the news in the complete versions sitting at the counter in the village shop. And, when an arrest was made, the suspect was not some highway robber, but Diana Delves Broughton’s husband, Sir Jock.

There was something particularly tragic about the idea that this sad old man might have been driven to such misery that he had murdered someone as young and vibrant as Joss. And this was the beginning of a serious decline for Idina. She was shaken enough to try to cross a war-torn Africa in search of a few days’ consolation from her husband. She drove to Kisumu airfield to see if she could cadge a lift north to Cairo, and Lynx.

CAIRO WAS TO THE SECOND WORLD WAR

what Paris had been to the First. It was a city held by the Allies but surrounded by battlefields. Six months earlier there had been a few thousand troops in the city. Now there were thirty-five thousand—in every Allied denomination

and all in search of diversion. The shops were full, Groppi’s café was still roasting its own coffee, and the white-gloved waiters at Shepheard’s Hotel were filling glasses with wine and champagne. In the spring of 1941, however, when Idina arrived, the city was welcoming a new flood of immigrants from the Balkans and Greece. Accommodations, cafés, restaurants, were all straining at the seams, and the heat was steadily rising. The hot khamsin desert wind and dust were suffocating the streets. Lynx was immersed in Air Force activity. After a few lonely days in the bar at Shepheard’s Idina decided to return to Kenya for Jock Delves Broughton’s trial. She had in any case promised to accompany the still suicidal Alice to the courtroom to watch. On her last day in the city Idina went to join the long queue in the bank to withdraw cash. As, after the best part of an hour, she reached the front, she heard the woman ahead of her give her name to the cashier: Mrs. David Wallace.

5

Idina approached the woman. She turned to face Idina. It was David’s wife, Pru, and, to what must have been Idina’s great joy, she was heavily pregnant. Pru had just been evacuated from Athens, where she and David had been working in the Embassy. With barely two weeks until the birth, she had sat in a small boat rocking its way out of Piraeus harbor, clutching a white Moses basket filled with things for her unborn child. So many bombs had fallen so close to the boat that she was frankly surprised to have made it to Cairo alive. But she didn’t yet know where David was, or whether he would reach her before the baby came. It was a big baby, she had been told. And it could arrive any day. She would tell David, when she saw him, that she had seen Idina. Then Idina watched her daughter-in-law turn firmly back to the cashier. Pru didn’t suggest that they stop for a coffee or meal, or even exchange addresses in order to meet another time. She was, Idina could see, just managing to cope with survival and impending childbirth in this strange, hot, dusty city. It was quite clear that she didn’t need or want to deal with anyone else too.

6

Pru certainly didn’t. As she later said, she already had one tricky mother-in-law, Barbie, back in England. The last thing she wanted then was another to deal with. Especially one who had not only abandoned her husband as a child but who, as far as she could see, would now do neither him nor the child she was carrying any good whatsoever,

7

as both the murder of one of her husbands and her own dissolute lifestyle were being plastered over the world’s press.

It was Idina’s turn at the cashier. She walked forward, withdrew her

money, and headed off to the airfield to see if she could find a flight home. Her first encounter with her daughter-in-law had not been promising. Pru’s coldness can hardly have filled her with hope of seeing much of what would be, once born, her first grandchild.

Idina returned to Kenya to find not just Alice but also Phyllis Filmer in a state over Joss’s death. Phyllis’s husband’s unsurprising inability to sympathize with her on this had finally cracked their marriage and she needed somewhere to live. Idina invited her to stay at Clouds until she had somewhere else to go.

The trial began on 26 May. Idina, Alice, and Phyllis turned up each day, dressed to the nines. They sat in the gallery and hung on every word of evidence given, their eyes burning holes in the back of Diana’s neck as their lives were pored over, scribbled down by court reporters, and wired back to the London and New York press. Regardless of who had actually pulled the trigger, as far as Idina was concerned, it was Diana who had killed her darling Joss.

Six weeks later Jock was acquitted, and Joss’s murder declared unsolved.

8

Alice, however, continued to decline. She started secretly labelling her possessions. To each item of furniture, each object, and each and every book, she attached a piece of paper with a name of one of the fifty people she had decided were her friends.

9

By late September she had finished. On the morning of the twenty-third she walked her dog, Minnie (Idina had the other in the pair, Mickey Mouse), across the lawn to the Wanjohi River. She pulled out a revolver and shot Minnie, burying her there. She then went back to her bedroom, where she had asked her servant to make up the bed with a set of extraordinarily ornate lace and linen sheets from her first marriage—each embroidered with the de Janzé crest. She picked up her bottle of sleeping pills and, one by one, swallowed the lot. Then she lay down and closed her eyes for the last time. The heyday of Idina’s Happy Valley was now over. For Alice was, as Idina had written to David, her “greatest friend in the world.”

10

The war, however, was not over. Idina settled into being her own land army, running the farm and, when she didn’t have friends up to stay, still careering down to Gilgil and Nairobi for weekend dances. From time to time Lynx came home on leave, but the gaps in between his appearances lengthened. Idina filled the emotional vacuum that followed this cascade of painful and violent deaths of people she loved with a series of affairs; she was vulnerable enough to need to. And she became increasingly indiscriminate in her choice of lovers, as if flailing

around for reassurance. Precious Langmead started walking over again in the afternoons. And, after that had ended again, came Arnold Sharp, an airman stationed at Gilgil. Arnold Sharp was, in Ann’s view, “poisonous,” and it was a “war sex” relationship only. The “terribly sweet and kind” Idina was “plagued by a terrible urge to get laid and have someone in bed with her.” She needed, says Ann, almost desperately to be loved, both by her two stepchildren and by the men who came through her life.

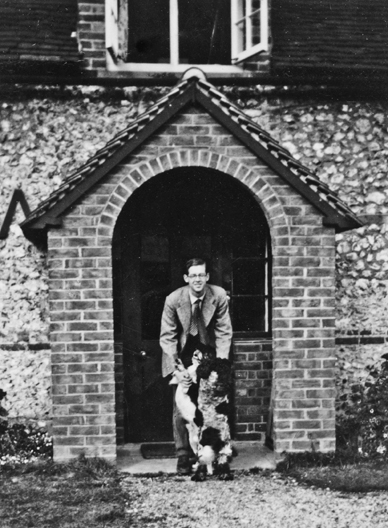

David at home in England, just before he left for Cairo, 1941

˙ ˙ ˙

IN THE SPRING OF 1943

Lynx came home with the news that he had been joined in Cairo by David. After the loss of so many young men in the First World War, the British government had been exercising a secret policy of keeping the most academically able away from the front line. David had therefore been, much to his frustration,

11

kept in barracks in Yorkshire while everyone else he knew seemed to be given the chance to fight for their country. He had spent endless evenings in the officers’ mess with men too old to fight again—and who spent the time reminiscing about dancing with Idina before the last war had even begun.

12

Eventually David had been selected to be the Foreign Office’s representative in Greece and had come to Cairo on his way there. He had been asked to contact the Greek guerrilla leaders and report on SOE’s (Special Operations Executive) activities there for the Foreign Office.

David had left two daughters, Idina’s granddaughters, Laura and Davina, behind in England. Laura had been born in Cairo in May 1941.

Davina had been born in June 1942, in the head gardener’s cottage at Lavington Park, a country estate that Barbie and Euan had bought shortly before the war. Barbie had never liked Kildonan,

13

and when Lavington, less than two hours’ drive south of London, came on the market at a surprisingly reasonable price, she had snapped it up without stopping to wonder why. While David was over in Cairo, Pru and the girls were living in the cottage on the grounds, grating along beside Barbie.

Gee, too, whom Idina had still not seen since he was a boy, had married. Like David, he had fallen in love with an older woman. This one, however, was old enough to be—and had been—the wife of one of Euan and Barbie’s friends, creating a small scandal.

14

But Gee and Elizabeth had married and were spending as much time as they could together until he was posted abroad.

15